We weep for you, Historic Ellicott City!

It is truly heartbreaking that this should have happened again. We were just there last Thursday, having dinner at our favorite restaurant, Tersiguel’s.

We pray for the missing man, Eddison “Eddie” Hermond, who was trying to assist a stranded woman when he was wept away by the raging waters.

And they were raging. The power of a swift current is incredible, and incredibly dangerous.

Information is available, including information on how to help the once again besieged residents and business owners, at The Community Foundation of Howard County.

Robicheaux fatigue, and a suggested remedy

Herewith are some excerpts from media reviews of Robicheaux:

Herewith are some excerpts from media reviews of Robicheaux:

James Lee Burke is what fellow writers call a wordsmith. He can make your eyes water with a lyrical description of tropical rain falling on a Louisiana bayou: “I love the mist hanging in the trees,” he tells us… “a hint of wraiths that would not let heavy stones weigh them down in their graves, the raindrops clicking on the lily pads, the fish rising as though in celebration.” But in the next breath, he’ll offer a comprehensive account of an excruciating death by torture: “The guy who did him took his time.” And to satisfy our appetite for Southern eccentricity, he’ll introduce us to great characters like Baby Cakes Babineau and Pookie the Possum Domingue.

Marilyn Stasio in The New York Times

Is this the last in the series of the great crime writer James Lee Burke’s novels featuring Cajun detective Dave Robicheaux? That eponymous title and an air of mortality as pungent as the semi-tropical Louisiana setting of these outstanding novels would suggest this may be the case.

It isn’t down to a diminishing of Burke’s powers at the age of 81 if so: this 21st instalment is as rewarding and superbly written as any in the series since the first, 1987’s The Neon Rain.

Alasdair Leeds in The Independent

Five years after his last case in far-off Montana (Light of the World, 2013), sometime sheriff’s detective Dave Robicheaux returns to Iberia Parish, Louisiana, for another 15 rounds of high-fatality crime, alcohol-soaked ruminations, and heaven-storming prose….

Despite a plot and a cast of characters formulaic by Burke’s standards (though wholly original for anyone else), the intimations of mortality that have hovered over this series for 30 years have never been sharper or sadder.

This is one of the best entries in one of the best ongoing crime-fiction series currently being published, and like all its predecessors, it’ll have readers eagerly waiting for the next installment.

Steve Donoghue in Open Letters Monthly

The novel’s murders and lies—both committed with unsettling smiles—will captivate, start to finish.

Arthur Miller once said that what separates the great artists from their merely proficient peers is not talent, intelligence, or dedication, but an “unquenchable moral thirst.”

If the late playwright was correct, then his insight serves as explanation for why and how James Lee Burke, one of America’s best novelists, continues to write profound, poetic and important books at the age of 81, after already having won two Edgar Awards — the most prestigious honor for crime writers — a Guggenheim fellowship, and a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize. Burke infuses into his art a theological treatment of ethics, allowing for acts against humanity — both of the smallest repute and the largest consequence — to crack open the essence of reality in contemporary America, but also resting in what Poe famously called, “the tell-tale heart.”

David Masciotra in Salon

I don’t usually read a book’s reviews right before writing up my own assessment. This time is different. I wanted to get some sense of what the reviewers had been saying that had made me want to return to this series, after having abandoned it more than twenty years ago.

Well, now I know. And am none the wiser. Which is to say, I’m somewhat perplexed at all the unqualified raves. In Robicheaux, there are a multitude of characters. This in itself is not unusual in full length mysteries these days. But a number of these characters veer into the action sideways, only to disappear just as abruptly. They were hard to keep track of, to the point where I stopped caring – always a bad sign. As for the plot: one of the reviewers described it as “multilayered.” I would have used the adjective “incoherent.” I cant be more specific at this time, since I read the book several weeks ago. But I doubt if I could have achieved an orderly retelling of the story even if I’d sat down to write this right after finishing the book.

And back to the characters, I recognized only two besides Dave Robicheaux, from previous books: Cletis “Clete” Purcel, Dave’s close buddy still wearing his signature pork pie hat, and Dave’s daughter Alafair, now grown and a successful novelist (like Burke’s real life daughter, also named Alafair). Other characters came and went; some stayed, like the shape changing Jimmy Nightingale. Some of these people verged on caricatures of Big Bad Southerners, obsessed with their guns, their drinking, and occasionally, their drugs.

Dave himself was still – well, Dave himself, ethical and upright to a fault (except when he wasn’t), still battling alcoholism, fiercely protective – overprotective I’d say – of Alafair. There were times when his air of moral superiority struck me as smug and irritating. A touch of comic relief would have helped, but there was very little of that on offer.

Regarding his home in southwestern Louisiana, Dave entertains a certain ambivalence. On the one hand:

Yes, Louisiana has produced some statesmen and stateswomen, but they are the exception and not the norm. For many years our state legislature has been known as a mental asylum run by ExxonMobil. Since Huey Long, demagoguery has bee a given; misogamy and racism and homophobia have become religious virtues, and self-congratulatory ignorance has become a source of pride.

Yet, on the other:

I looked the oaks, the moss lifting in the wind, purple dust rising from a cane field, Bayou Teche glinting in the sun like a Byzantine shield. La Louisiane, the love of my life, the home of Jolie Blon and Evangeline and the great Whore of Babylon, the place for which I would die, the place for which there was no answer or cure.

And yes, there is plenty more writing of that caliber. Burke is well known for his way with words in general, and for his poetical descriptions of Louisiana in particular. Tony Hillerman managed to lure me – twice – into visiting New Mexico. (I’d go again in a heartbeat.) James Lee Burke’s depiction of south central Louisiana doesn’t have quite the same effect. Although….

Bayou Teche, near Dave’s home, is a real place.

I found two aspects of this novel profoundly off putting. First, the language was beyond coarse and vulgar, filled with profanity and references to body parts that you’d rather not talk about. Second, the violence was frequent, graphic, and spiked with sickening acts of sadism.

Even so, I pushed ahead to the end, wanting to give the novel every chance to redeem itself in my eyes. And well, the ending was rather fitting, ironic, even sad. It made you wonder what all the effort was for.

Mostly I was just glad it was over. Would I ever read another? If I thought there were a hope for something more humane and less savage, I might.

There was a time when I was so hooked on this series that its unearthly setting invaded my dreams. From 1989, the pub year of the Edgar-award-winning Black Cherry Blues, through A Morning For Flamingos and A Stained White Radiance to In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead, published in 1993, I was a faithful reader. In that last novel, Burke evoked the spirits of the doomed soldiers of the Old South, as they slogged through the swamps and lit their campfires where they could. Those men still haunt Robicheaux in this novel. It’s a powerful and haunting trope.

I went straight from this unsettling reading experience to another of Ann Cleeves’s Vera Stanhope mysteries. Vera’s no paragon of perfection either, but she’s honest with herself and with others, smart as a whip, and very sympathetic where sympathy is called for. The violence is muted; the language is low key yet devastating. This one was called Harbour Street.

A Mother’s Day Visit to The Art Institute

Our goals this time were to visit our former favorites, find some new favorites, and of course, have as much fun as possible.

Our old friends were right where we left them when last we visited (this being one of the excellent things about museums).

Etta and I have grown somewhat sentimental about this bizarre Roman theater mask. Seeing it for the first time, Welles was properly amazed – “He’s got a hand in his mouth!”

Of course we greeted Degas’s Little Dancer:

And Georges Seurat’s Un Dimanche Après-Midi à L’Île de La Grande Jatte:

Each time we visit this place, we see something new (to us) and wonderful:

…and Gorgeous Little Girl in White Dress and Shoes of Gold… Ah, well, no chance of objectivity here!

I’d never heard of Arthur Devis but I was completely captivated by this work. How did I miss it until now?

Etta and I made our rounds together; Welles and his Mom went a different way. When we met up, Welles was nearly beside himself with excitement. He had something truly wonderful to show his big sister! So upstairs we trooped to the Kania Collection, and lo and behold, what did we find there but this:

Officially designated as “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA),” this work – in some places referred to as an installation – is by the Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres and is dated 1991. The Art Institute site describes it as follows:

Officially designated as “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA),” this work – in some places referred to as an installation – is by the Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres and is dated 1991. The Art Institute site describes it as follows:

Candies individually wrapped in multicolor cellophane, endless supply

Dimensions vary with installation; ideal weight 175 lbs.

An endless supply of candy! Surely this is the stuff of dreams, especially for children, and especially for Welles, a confirmed candy aficionado at the age of four. (‘Endless supply’ translates into the fact that visitors may help themselves to the sweet stuff, as long as it’s promptly replenished by staff.)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres‘s life was tragically cut short: he died in 1996 at the age of 38. But with this work, he gave joy to my grandchildren and no doubt to others as well. I am grateful to him.

***************

As for that other famed denizen of the Art Institute, alas, it is still at the Whitney in New York. I mean, of course, Grant Wood’s American Gothic:

This is the fourth time in the past two years that I’ve come to the Art Institute and missed seeing it! I must have faith that it will some day come home – sigh….

As usual, we finished our visit at the museum’s gift shop. There are two, actually, both equally filled with a tantalizing selection of goodies. The array of art books is truly impressive; there was an entire rack of these from my current favorite art book publisher, Taschen.

Among the other merchandise, I particularly love a series of hand painted silk scarves by Chicago artist Joanna Alot. This time I came away with this beauty:

As for the children, they selected kits of modeling clay. Welles and Etta are lively, energetic, and affectionate. Sometimes it is all their no-longer-young grandmother can do to keep up with them! And yet, once home from the museum, they became lost in clay play. Etta was creating her own version of marbles; Welles was making small containers for them. (It is absolutely necessary for Welles to have at least part of his vast collection of Hot Wheels nearby, whenever he undertakes a project of this sort – or just anytime.)

Watching them so quietly absorbed in these projects, I was reminded once more of the miracle of their existence, and of my equally miraculous and boundless love for them. And many thanks, too, to their Mom, my beautiful daughter-in-law, for making all of this possible.

Phillip Roth

I have very little to add to the numerous articles and essays on the subject of this great and often controversial writer. I grew up surrounded by his works, and discussion of his works, sometimes heated, within my own family circle and among friends.

Roth’s Newark, New Jersey origins closely mirrored mine, just up – down? – the road in West Orange. My family always felt a strong, if strained, kinship with him. Family legend has it that one of my uncles attended Weequahic High School at the same time as Roth.

The Wikipedia entry has a list of the complete oeuvre. Of those, I’ve read the following:

The Ghost Writer

Zuckerman Unbound

The Human Stain

Exit Ghost

The Dying Animal

Everyman

Patrimony: A True Story

That last, a memoir of the final illness and death of his father Herman Roth, was deeply moving. My favorite from among the novels I’ve read is The Human Stain. American Pastoral is often cited as his masterwork.

Roth often wrote as it he were regaling, even haranguing, his interlocutor. His writing was mercilessly direct and utterly without affectation. The following, from The Human Stain, describes the narrator’s experience attending a rehearsal at The Tanglewood Music Center in western Massachusetts:

As the audience filed back in, I began, cartoonishly, to envisage the fatal malady that, without anyone’s recognizing it, was working away inside us, within each and every one of us: to visualize the blood vessels occluding under the baseball caps, the malignancies growing beneath the permed white hair, the organs misfiring, atrophying, shutting down, the hundreds of billions of murderous cells surreptitiously marching this entire audience toward the improbable disaster ahead. I couldn’t stop myself. The stupendous decimation that is death sweeping us all away. Orchestra, audience, conductor, technicians, swallows, wrens—think of the numbers for Tanglewood alone just between now and the year 4000. Then multiply that times everything. The ceaseless perishing. What an idea! What maniac conceived it? And yet what a lovely day it is today, a gift of a day, a perfect day lacking nothing in a Massachusetts vacation spot that is itself as harmless and pretty as any on earth.

Then Bronfman appears. Bronfman the brontosaur! Mr. Fortissimo! Enter Bronfman to play Prokofiev at such a pace and with such bravado as to knock my morbidity clear out of the ring. He is conspicuously massive through the upper torso, a force of nature camouflaged in a sweatshirt, somebody who has strolled into the Music Shed out of a circus where he is the strongman and who takes on the piano as a ridiculous challenge to the gargantuan strength he revels in. Yefim Bronfman looks less like the person who is going to play the piano than like the guy who should be moving it. I had never before seen anybody go at a piano like this sturdy little barrel of an unshaven Russian Jew. When he’s finished, I thought, they’ll have to throw the thing out. He crushes it. He doesn’t let that piano conceal a thing. Whatever’s in there is going to come out, and come out with its hands in the air. And when it does, everything there out in the open, the last of the last pulsation, he himself gets up and goes, leaving behind him our redemption. With a jaunty wave, he is suddenly gone, and though he takes all his fire off with him like no less a force than Prometheus, our own lives now seem inextinguishable. Nobody is dying, nobody—not if Bronfman has anything to say about it!

I have a vague memory of a feature article that appeared some years ago in the Washington Post (or possibly The New York Times). It was entitled “Lions in Winter,” those lions – if memory serves, and it may not – being Saul Bellow, E.L. Doctorow, Joseph Heller, Phillip Roth, and John Updike. Now they are all gone, yet not gone, and well worth revisiting, each of them, but especially, today, Phillip Roth.

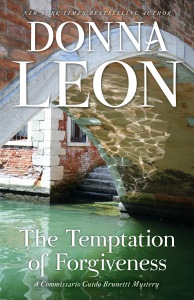

The Temptation of Forgiveness by Donna Leon

In general, I’m a big fan of Donna Leon’s mysteries. Guido Brunetti is one of the most humane and compassionate officers of the law that one could ever wish to meet, either in fiction or in real life. His family, consisting of wife and university professor (and fabulous cook) Paola and children Raffi and Chiara, now almost grown, are a pleasure to spend time with. Alas, in this latest outing, we don’t get to see much of them. This may be one of the reasons why I was less than thrilled with this particular series entry.

In general, I’m a big fan of Donna Leon’s mysteries. Guido Brunetti is one of the most humane and compassionate officers of the law that one could ever wish to meet, either in fiction or in real life. His family, consisting of wife and university professor (and fabulous cook) Paola and children Raffi and Chiara, now almost grown, are a pleasure to spend time with. Alas, in this latest outing, we don’t get to see much of them. This may be one of the reasons why I was less than thrilled with this particular series entry.

The writing is, in a crisp and unaffected way, wonderful. In this scene, Brunetti has seated himself by the hospital bed of an unconscious, badly bruised man.

He crossed his legs and studied the crucifix on the wall. Did people still think He could help them? Maybe being in the hospital refreshed their belief and made it possible again for them to think that He would. One gentleman to another, Brunetti asked the Man on the cross if He would be kind enough to help the man in the bed. He was lying there, perhaps troubled in spirit, helpless, wounded and hurt, apparently through no fault of his own. It occurred to Brunetti that much the same could be said of the Man he was asking to help; this would perhaps make Him more amenable to the request.

This scene actually surprised me, since Brunetti has, throughout this series, thought of himself as at best, an agnostic. Thus does belief sometimes steal upon us, taking us unaware, even if just momentarily.

(In The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, Sarah says, “I’ve caught belief like a disease. I’ve fallen into belief like I fell in love.”)

All this time, the victim’s wife is also in the hospital room, anxiously waiting for him to awaken. At one point, an attendant comes in and offers her a simple courtesy, which she desperately needs. Brunetti thanks the attendant for her kindness.

She was a robust women, stuffed into a uniform she seemed to be outgrowing. One loose strand of greying hair had slipped from under the transparent plastic-shower-cap thing; her hands were red and rough. She smiled. St.Augustine was wrong, Brunetti realized: it was not necessary for grace to be arrived at by prayer; it was as natural and abundant as the sunlight.

And so, what about that unconscious man? How did he get that way, and what is his fate to be? Unfortunately, this aspect of the novel was, for this reader at least, not especially compelling. The narrative dragged in places; the interviews were less than riveting. Ultimately, the solution to the mystery hinges on a fistful of discount cosmetic coupons issued by a pharmacist to an elderly lady. This transaction was analyzed at length; it was confusing and just plain dull.

Concerning Brunetti’s workplace colleagues, there are two who are portrayed in a positive light: fellow investigator Claudia Griffoni, a relatively new addition to the cast of characters; and Signorina Elettra Zorzi. Signorina Elettra, as she is usually called, is a civilian employee of the police, whose resourcefulness is legendary (as is her wardrobe).

Donna Leon has expressed her delight at the entrance of Signorina Elettra into the cast of characters in the Brunetti novels. Here’s how she puts it in an interview:

She came about one day a long time ago. I forget when she entered, the 3rd or 4th book. (the 3rd book) Really, that long ago. I was writing and someone knocked on Brunetti’s door and I didn’t have a clue who it could be or what it could be. So I went for a long walk, probably down to Sant Elena and I came back and turned on the computer and by God Signorina Elettra walked in and Thank God for the day that she did.

Not everyone is enamored of this character. One reader who most definitely isn’t is my friend Marge, whom I’ve referred to in the past as my ‘partner in crime,’ since she was the one who explained to me, when I first came to work at the library, why I should be reading mysteries. Marge is so put off by the presence – some would say the intrusive presence – of Elettra that she has stopped reading this series altogether. Ah mon Dieu! Now I’m not crazy about her either, but I don’t dislike her quite to that extent. And as I’ve indicated above, this latest is, in my view, not Donna Leon’s best work. But in a series thus far comprising twenty-seven novels, some are bound to better than others. My favorite among the more recent titles is The Waters of Eternal Youth.

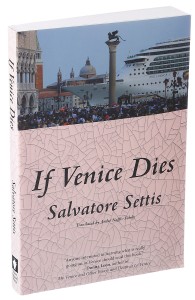

One aspect of the Brunetti novels that is a constant, and that gives great pleasure, is the setting. The city of Venice is almost a character in and of itself, unique and imperiled as it currently is. I recently read a review of a 2016 book by Salvatore Settis entitled If Venice Dies. The cover pretty well sums up the crux of the problem (click to enlarge):

Let’s hope something can be done, and in time. Meanwhile, I along with many others will continue to read the Brunetti novels and to ponder the exasperating glory of that unique city.

A singular type of novel that shouldn’t be suspenseful, but nonetheless is

There needs to be a special subgenre designation for novels in which the occurrence of an overarching historical event is commonly known from the outset. This event will – must – affect the characters’ lives in ways they could never have anticipated as the narrative gets under way. In effect, the reader is vouchsafed crucial knowledge to which the characters themselves have no access.

I can think of three titles I’ve read that fall into this category:

I read Beryl Bainbridge’s novel of the Titanic disaster when it came out in 1996. I don’t remember any of the particulars, only that I enjoyed it tremendously. Bainbridge has a unique take on historical fiction that’s worth seeking out. According to Queeney, the story of Dr. Johnson and his rather bizarre attachment to the hapless Hester Thrale, is my other favorite from among her works.

As for Pompeii, well, we all know the sad fate that overwhelmed the denizens of that city as well as those of Herculaneum in 79 AD. In the novel, Marcus Attlius Primus, an hydraulic engineer, has been to the region close to Mt. Vesuvius in order to investigate a malfunction of one of Rome’s famous aqueducts. (Again I must apologize for the vagueness of my recollections. I also read this book when it came out, in 2003.) At one point in the narrative, he and some others are talking and imbibing a liquid (wine? water?). A full glass is set down on the table before them, and for reasons not apparently obvious to those present, the surface of the liquid becomes strangely agitated.

For several years now, we’ve been making our morning coffee with a Keurig machine. We always have a plastic cup filled with water at the ready so as to top up the machine’s reservoir. As the coffee is being made, the machine emits a low, rather loud droning sound for several seconds. As it does so, this happens to the surface of the water in the cup:

Every time I see it happen, I think of Pompeii – and Pompeii. (When I was in Italy, I noted the name was spelled Pompei.)

Robert Harris is an amazing writer. He seems to be able to tackle any kind of scenario, whether historical or contemporary, and tell a story so gripping that you want only to be left alone to read it.

The third work I’m thinking of is not concerned not with a cataclysm that is part of the greater historical record. Rather, it has to do with the fate of one family. How then is the reader apprised of this particular event that waits malevolently in the wings? Simple: the author of A Judgement in Stone, Ruth Rendell, states bluntly in the first sentence:

The third work I’m thinking of is not concerned not with a cataclysm that is part of the greater historical record. Rather, it has to do with the fate of one family. How then is the reader apprised of this particular event that waits malevolently in the wings? Simple: the author of A Judgement in Stone, Ruth Rendell, states bluntly in the first sentence:

Eunice Parchman killed the Coverdale family because she could not read or write.

What Rendell has done is to set up the pull of an enormous dread that runs throughout the novel. It is a gigantic thread whose strength the reader struggles against even as it grows ineluctably stronger. Can nothing be done to prevent this horror – to save these blameless people? you ask yourself. Of course, the answer is no, nothing can.

In Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part Two, the King cries out in anguish: “O God, that one might read the book of fate…” A Judgement in Stone can make you feel relieved – even glad – that you cannot do so.

************

This line of thought was occasioned by my recent reading of The Throne of Caesar, Steven Saylor’s superb new novel of Gordianus the Finder.

‘–a man as close to godhead as any mortal who had ever lived–could such a man be alive one moment…and dead the next?’ – The Throne of Caesar by Steven Saylor

The Throne of Caesar begins in this wise:

The Throne of Caesar begins in this wise:

Once upon a time, a young slave came to fetch me on a warm spring morning. That was the first time I met Tiro.

Gordianus hastens to inform us that this was a long time ago. Now, Tiro is no longer a slave. He is a freedman, having been manumitted some years ago by his master Cicero. And after the passage of many years and the experience of numerous adventures, Gordianus, called Finder, is quite a bit older and, he hopes, wiser. His family is flourishing. The omens are propitious. And he himself is about to be receive an unexpected and significant honor, bestowed by none other than the great Julius Caesar, with whom he has become a favorite.

What could possibly go wrong? Here’s a clue: the novel opens with a page upon which only the date is divulged. That date is March 10.

That’s right; six days before one of the most famous dates in the history of the Western World: March 15, the Ides of March.

So: do we readers just wait in dread of the inevitable? Well, that element of suspense is certainly present from the start, but much else is going on as well. Gordianus’s son Meto has become indispensable to Caesar as his secretary and general right hand man. Daughter Diana and her husband, the hulking bodyguard Davus, live with Gordianus and his wife, the beautiful and imperious Bethesda. (One imagines that no one has ever done “imperious” quite the way the Roman matrons did.) Cinna the poet is a favorite drinking buddy of Gordianus’s. The great orator Cicero, somewhat past his prime, is nervously on the scene. And then there’s the haruspex Spurinna….

A haruspex was a soothsayer who specialized in the reading of entrails. This skill was closely identified with the religion of the Etruscans.

Spurinna was supposedly the name of the soothsayer who has warned Caesar to “Beware the Ides of March.” One of the most chilling moments in Shakespeare’s play occurs when, on his way to the Senate, Caesar encounters Spurinna for the second time. Feeling rather full of himself, Caesar observes that “The Ides of March are come.” To which the soothsayer responds, without missing a beat, “Ay, Caesar, but not gone.”

And yet, in the days before the Ides, life goes on, filled with plots, counter- plots, and various intrigues, and gossip, just as the Romans loved it. Also, at the time, poetry played a big part in the cultural life of the people. Cinna’s latest opus, entitled Zmyrna, was incessantly read and talked about. (The author’s full name is Helvius Cinna, not to be confused with Lucius Cornelius Cinna, praetor and conspirator. Alas, despite the protestations of Helvius Cinna, that confusion does in fact occur, with disastrous results for the poet. You’ll recall Shakespeare’s memorable line: “Tear him for his bad verses, tear him for his bad verses.”)

At any rate, back to Zmyrna: Impatient with his father’s delay in reading this putative masterpiece, Meto begins reading aloud to him. Here’s how Gordianus responds:

I thought I would prefer those moments when Meto read aloud, for he had a beautiful voice and knew exactly where to place each stress depending on the secret meanings of the words. But I enjoyed just as much the experience of reading the verses aloud myself, letting my lips and tongue play upon the absurdly convoluted edifice of language. Even when I didn’t quite understand what I was reading, the words themselves produced music. When I did understand not merely the outermost level of meaning but also the multiple puns and learned references, I felt an added thrill, as if the words that emerged from my mouth were truly something more than air, compounded of some enchanted substance that encircled and gently caressed both Meto and myself.

Beautiful description that, and how eloquently it limns the closeness and mutual affection of father and son. (When I went in search of the actual Zmyrna, I was informed succinctly by Wikipedia that “The poem has not survived.”)

Oh and speaking of ‘learned references,’ Caesar, during a later literary-themed conversation, comes up with this idea:

“Imagine a series of life stories told in parallel, to compare and contrast the careers and fortunes of great men.”

Of course, Plutarch not only imagined this, he wrote it, some hundred and fifty years after Caesar’s fanciful speculation, as rendered by Steven Saylor.

Here’s another set piece that I love. This is actually the same occasion at which Caesar made the comment above:

To either side of me, braziers burned. Torches flickered from various sconces in the surrounding portico. The last faint light of day lit the ashen sky, in which the first stars had begun to shine. The four men moved amid green shrubs and tall statues. The ever-changing light, the men in their finery, the looming figures of marble, and bronze–all combined in a moment of surpassing strangeness. I looked at Meto, wondering if he, too, felt it. On his face I saw a look of deep contentment that increased with each step that brought Caesar nearer.

Scenes like this, with their portentous quietude, serve to make the intimations of coming bloodshed feel all the more harrowing.

Steven Saylor obviously derives a deep joy from a lifelong immersion in the life and literature of ancient Rome. He passes that joy directly on to us, the readers of his Roma Sub Rosa series. His erudition is everywhere evident, but it never hijacks the narratives, which are invariably compelling, set as they are against a background of actual events from ancient times. Those times spring vividly to life in his stories of ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events. It cannot be an easy task to conjure a world whose inhabitants had such a drastically different world view than our own. (It’s hard, for instance, to accept the fact that educated, cultured individuals gave credence to the reading of animal entrails.) And yet this author accomplishes this feat, with conviction and brio.

The art work that graces the cover of The Throne of Caesar is by Karl Theodor Piloty and was painted in 1865.

I also like this version of the event, painted by Jean-Leon Jerome in 1867.

On Steven Saylor’s richly informative site, I note with delight a celebration of the 25th anniversary of the publication of Roman Blood. How well I remember reading it when it came out in 1991 and thinking, Wow, what a winner this is!

I ask only this of any work of historical fiction that I read: Put me there, in that place, at that time. This is, after all, the only form of time travel we have, so make it work. In his marvelous series of novels treating of the life and times of Gordianus the Finder, proud and resourceful citizen of ancient Rome, Steven Saylor (whom we had the pleasure of meeting at Crimefest in 2011) does exactly that.