Peter Robinson

I am saddened by the death of Peter Robinson. He has long been one of my favorite mystery writers. Marge, my close friend, coworker at the library, and ‘Partner in Crime’ – we discovered him at the beginning of his career, with the publication of Gallows View in 1987. Since then, we have followed the adventures of the music-loving Detective Chief Inspector Alan Banks, in both his professional and his personal life. He had his ups and downs in both. The last novel in the series is Not Dark Yet (2021).

The vivid Yorkshire setting combined with intriguing characters kept many readers happily hooked on this series. In particular, Peter Robinson wrote the kind of police procedural novel at which the British have long excelled, and which is, alas, becoming all too rare.

At any rate, we’re grateful for his contribution to the field of crime writing. He will be greatly missed.

Phillip Roth

I have very little to add to the numerous articles and essays on the subject of this great and often controversial writer. I grew up surrounded by his works, and discussion of his works, sometimes heated, within my own family circle and among friends.

Roth’s Newark, New Jersey origins closely mirrored mine, just up – down? – the road in West Orange. My family always felt a strong, if strained, kinship with him. Family legend has it that one of my uncles attended Weequahic High School at the same time as Roth.

The Wikipedia entry has a list of the complete oeuvre. Of those, I’ve read the following:

The Ghost Writer

Zuckerman Unbound

The Human Stain

Exit Ghost

The Dying Animal

Everyman

Patrimony: A True Story

That last, a memoir of the final illness and death of his father Herman Roth, was deeply moving. My favorite from among the novels I’ve read is The Human Stain. American Pastoral is often cited as his masterwork.

Roth often wrote as it he were regaling, even haranguing, his interlocutor. His writing was mercilessly direct and utterly without affectation. The following, from The Human Stain, describes the narrator’s experience attending a rehearsal at The Tanglewood Music Center in western Massachusetts:

As the audience filed back in, I began, cartoonishly, to envisage the fatal malady that, without anyone’s recognizing it, was working away inside us, within each and every one of us: to visualize the blood vessels occluding under the baseball caps, the malignancies growing beneath the permed white hair, the organs misfiring, atrophying, shutting down, the hundreds of billions of murderous cells surreptitiously marching this entire audience toward the improbable disaster ahead. I couldn’t stop myself. The stupendous decimation that is death sweeping us all away. Orchestra, audience, conductor, technicians, swallows, wrens—think of the numbers for Tanglewood alone just between now and the year 4000. Then multiply that times everything. The ceaseless perishing. What an idea! What maniac conceived it? And yet what a lovely day it is today, a gift of a day, a perfect day lacking nothing in a Massachusetts vacation spot that is itself as harmless and pretty as any on earth.

Then Bronfman appears. Bronfman the brontosaur! Mr. Fortissimo! Enter Bronfman to play Prokofiev at such a pace and with such bravado as to knock my morbidity clear out of the ring. He is conspicuously massive through the upper torso, a force of nature camouflaged in a sweatshirt, somebody who has strolled into the Music Shed out of a circus where he is the strongman and who takes on the piano as a ridiculous challenge to the gargantuan strength he revels in. Yefim Bronfman looks less like the person who is going to play the piano than like the guy who should be moving it. I had never before seen anybody go at a piano like this sturdy little barrel of an unshaven Russian Jew. When he’s finished, I thought, they’ll have to throw the thing out. He crushes it. He doesn’t let that piano conceal a thing. Whatever’s in there is going to come out, and come out with its hands in the air. And when it does, everything there out in the open, the last of the last pulsation, he himself gets up and goes, leaving behind him our redemption. With a jaunty wave, he is suddenly gone, and though he takes all his fire off with him like no less a force than Prometheus, our own lives now seem inextinguishable. Nobody is dying, nobody—not if Bronfman has anything to say about it!

I have a vague memory of a feature article that appeared some years ago in the Washington Post (or possibly The New York Times). It was entitled “Lions in Winter,” those lions – if memory serves, and it may not – being Saul Bellow, E.L. Doctorow, Joseph Heller, Phillip Roth, and John Updike. Now they are all gone, yet not gone, and well worth revisiting, each of them, but especially, today, Phillip Roth.

Joan

My beloved sister-in-law Joan has said farewell to life in this world. She leaves behind a large circle of family and friends, all of whom cherished her wit, cheerfulness, loyalty, and unstinting generosity. These qualities, which she possessed in abundance, will remain with us.

Several years ago, Joan and I were talking about poetry and the possibility of an afterlife. Wordsworth’s “Ode on Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” came into the conversation – specifically this passage:

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star,Hath had elsewhere its setting,And cometh from afar:Not in entire forgetfulness,And not in utter nakedness,But trailing clouds of glory do we comeFrom God, who is our home:******************************

We bid farewell to Colin Dexter

I’ve been trying to brace myself for this news, but it hurts all the same.

Colin Dexter autographing my copy of The Jewel That Was Ours at the Randolph Hotel in Oxford in 2006. Our tour group had the impression that he was enjoying himself hugely. Someone asked him why he had to kill Morse, and he responded, sounding – and looking – somewhat injured: “But I didn’t kill him – He died of natural causes!”

Few English families living in England have much direct contact with the English Breakfast. It is therefore fortunate that such an endangered institution is perpetuated by the efforts of the kitchen staff in guest houses B & B’s, transport cafes, and other no-starred and variously starred hotels. This breakfast comprises (at it best): a milkily-opaque fried egg; two rashers of non-brittle, rindless bacon; a tomato grilled to a point where the core is no longer a hard white nodule to be operated upon by the knife; a sturdy sausage, deeply and evenly browned; and a slice of fried bread, golden-brown, and only just crisp, with sufficient fat not excessively to dismay and meddlesome dietitian.

Our tour group met Dexter at the Randolph hotel in downtown Oxford. A room was set aside where he could wax expansive and witty, chatting with us agreeably and holding us spellbound.

I felt very lucky that day. I’d met my favorite author and enjoyed some precious time in his company.

Lewis smiled in spite of himself. Why he ever enjoyed working with this strange, often unsympathetic, superficially quite humorless man, well, he never quite knew. He didn’t even know if he did enjoy it.

Dexter wrote thirteen Morse novels and also some short stories. He was not especially prolific (though the filmmakers were: There are thirty-three episodes in all). Dexter closed out the series in 1999 with The Remorseful Day. Although I’ve read the novel, I was never able to bring myself to watch the tv episode. The death of 60-year-old John Thaw, three years after the demise of his fictional counterpart, was especially poignant.

Morse thought it must be the splendid grandfather clock he’d seen somewhere that he heard chiming the three-quarters (10:45 a.m.) as he and Lewis sat beside each other in a deep settee in the Lancaster Room. Drinking coffee.

“We’re getting plenty of suspects, sir.”

“Mm. We’re getting pretty high on content but very low on analysis, wouldn’t you say? I’ll be all right though once the bar opens.”

“Is is open–opened half-past ten.”

“Why are we drinking this stuff, then?”

One of the most memorable book discussions I led while still at the library was of The Jewel That Was Ours. The quoted passages above are all from that novel. Somewhat confusingly, the tv version is title The Wolvercote Tongue. (The tv script apparently preceded the novel in order of composition.) At the end of that episode, divers are shown making desperate effort recover the jewel from the river. When one of them finds it, he holds it aloft in a manner that instantly puts one in mind of the Lady of the Lake clutching Excalibur.

As we were leaving, Oxford, Colin Dexter joined us as our bus proceeded through ‘leafy North Oxford.’ He graciously offered to point out the sights along the way. My husband recorded his commentary.

I especially like the obituary in The Independent.

For his services to literature, Colin Dexter was awarded the OBE in 2000.

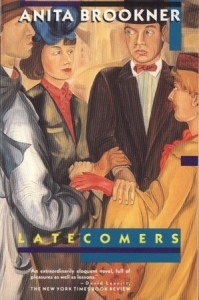

Anita Brookner

I am saddened by the passing of Anita Brookner. Over the years, my reading life has been greatly enriched by her novels. She wrote twenty-four of them; I’ve read some thirteen or fourteen. That sounds like a lot, but they are slender volumes, meticulously crafted. I’ve always admired her writing and her intellect; she possessed a large vocabulary which she deployed with pointillist precision.

I am saddened by the passing of Anita Brookner. Over the years, my reading life has been greatly enriched by her novels. She wrote twenty-four of them; I’ve read some thirteen or fourteen. That sounds like a lot, but they are slender volumes, meticulously crafted. I’ve always admired her writing and her intellect; she possessed a large vocabulary which she deployed with pointillist precision.

As a writer for the Catholic Herald notes of Brookner, “her heroines and occasional heroes were people whom by and large life had passed by: their pleasures were small ones, and the great storms of passion were things that happened to other people.” This makes her characters sound somewhat dreary, but I think it would be more accurate to call most of them introverted, with a propensity for melancholy. At this point, one wants to assert hastily that they had rich inner lives. But if memory serves, that’s not always the case. In truth, memory is not serving me all that well at the moment, as I’ve not read anything by her since Strangers came out in 2009.

To my mind, Anita Brookner had always seemed a quintessentially English novelist. I’ll bet she’s got one of those distinguished British pedigrees that goes back several hundred years, thought I. Well she might – but not in Britain. Her parents were Polish Jews who emigrated in the early years of the 20th century. (I was genuinely surprised to learn this about her.) She was their only child.

Having earned a PhD in art history from London’s famed Courtauld Institute, Brookner went on to teach and write in that field. She wrote her first novel – A Start in Life, published here in 1981 as The Debut – when she was 53.

An interesting sidelight regarding Brookner’s time studying at the Courtauld is that one of her professors was a highly respected art historian who held the post of Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures. His name was Anthony Blunt.

Ring a bell? Blunt was one of the Cambridge Spies, the most famous of which is probably Kim Philby. I’ve known for quite some time that Brookner studied art history under Blunt, but there’s a story concerning the two of them and a third individual that I’d never heard until I started looking for material for this post. It’s told by A.N. Wilson in the Daily Mail:

As a distinguished scholar at the Courtauld Institute in London, Britain’s foremost centre of art history studies, Anita Brookner worked with Anthony Blunt, the Keeper of the Queen’s pictures, who was later exposed as a traitor.

When one of their equally distinguished colleagues, Phoebe Pool, had a nervous breakdown and ended up in a mental hospital, Blunt asked Brookner to visit Pool regularly.

She did so happily, unaware Blunt was a Soviet agent, nor that he had used Pool — once an enthusiastic member of the Communist party — as a go-between to take messages to his Russian spymaster.

Every time Anita Brookner came back from the hospital after seeing Pool, Blunt would quiz her. How was Phoebe? Had she blurted out any names? Which names? The questions meant nothing to Brookner. She had no idea that the names Pool might have let slip could have belonged to spies.

It was only when, decades later, Blunt and the more minor figure of Pool were unmasked that she realised she had been a pawn in the Cold War. Brookner’s reactions were entirely typical. Yes, she was very angry, and went on being angry with Blunt to the end of her days.

She felt she had been ‘manipulated’ by him, and realised, going back over their conversations, that he had tried to enlist her as an agent.

Though one of the most intelligent women alive, she confessed that she had been ‘too stupid’ to realise what he was on about.

Wilson adds that despite feeling used and manipulated when the truth about Blunt became publicly known (in 1979), Brookner retained a degree of loyalty to her erstwhile mentor: “She owed her job as an art historian to Blunt, who admired her scholarship and her knowledge of 17th and 18th-century French paintings.”

Although Brookner’s fiction is usually been held in high esteem, there are some who feel that in later years, the scope of her novels became increasingly constricted. As Matt Schudel states in the Washington Post: “By the mid-1990s, some critics had become weary of what some called an attenuated, bloodless quality that seemed to owe too much to earlier styles.”

Attenuated? Bloodless? Not to this reader (nor to many others). Instead, I felt that with each new novel I was given the chance to examine a different facet of a beautiful and enigmatic jewel. The spell was cast every time. I was always grateful.

If you are new to the fiction of Anita Brookner, you should probably start with Hotel Du Lac. This is her Booker Prize winner, a justly cherished novel. I’d like to reread Latecomers; it’s the only Brookner title I’ve read that dealt specifically with Eastern European immigrants living in Britain. And I have yet to read her final fiction: At the Hairdresser’s, available in e-book format only.

If you are new to the fiction of Anita Brookner, you should probably start with Hotel Du Lac. This is her Booker Prize winner, a justly cherished novel. I’d like to reread Latecomers; it’s the only Brookner title I’ve read that dealt specifically with Eastern European immigrants living in Britain. And I have yet to read her final fiction: At the Hairdresser’s, available in e-book format only.

Jonathan Yardley, formerly a writer and reviewer for The Washington Post Book World, used to run an occasional column called Second Reading, where he called attention to older titles that might be worth revisiting as well as current authors who might be unjustly neglected. It was a marvelous feature. My favorite of all those columns was ostensibly about Isabel Colegate’s The Shooting Party, but Yardley ended up writing about five additional authors as well, all women. Anita Brookner was one of them, as well as two other favorites of mine (in addition to Colegate): the Penelope’s, Fitzgerald and Lively. (Yardley’s ‘Second Reading’ pieces are collected in a book of the same name.)

In addition to the links above, two other articles about Brookner that are well worth reading can be found in The Guardian and The New York Times.

Farewell to Henning Mankell, crime fiction sage of the north country

Yesterday, I was saddened by news of the passing of Henning Mankell. I’ve enjoyed his crime fiction a great deal. The first Kurt Wallander novel I read was One Step Behind; from that moment, I knew I’d be reading more. (Among other things, Wallander was struggling with Type Two Diabetes, just as I was. So I guess that helped me to bond with this character.) Other Kurt Wallander novels I’ve read and greatly liked by Mankell are The Dogs of Riga and Firewall. In 2009 (2011 in this country), Mankell closed this series out with The Troubled Man, a real tour de force, in my opinion.

I also read Before the Frost, in which Wallander’s daughter Linda takes center stage. Mankell had intended to continue with this series, but a tragedy intervened that it made it impossible for him to write any more novels featuring Linda Wallander. Click here to read more about what happened.

I also read Before the Frost, in which Wallander’s daughter Linda takes center stage. Mankell had intended to continue with this series, but a tragedy intervened that it made it impossible for him to write any more novels featuring Linda Wallander. Click here to read more about what happened.

Stieg Larsson, author of the Dragon Tattoo novels featuring the memorable Lisbeth Salander, is often given credit for initiating a second Golden Age in Swedish crime fiction. (The first began with the great creative team of Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, whose Martin Beck series dates from 1965 to 1975.) There’s no getting around the sensation caused by Larsson‘s singular and highly original creation, but Henning Mankell also deserves credit for once again focusing the spotlight on the masterful mysteries issuing from his native land.

I regret that there will be no further insightful, ruminative prose issuing from his pen.

Oliver Sacks

I’d like to acknowledge the passing of Oliver Sacks, physician and writer. Dr. Sacks has been submitting luminous essays and op-ed pieces to the New York Times regularly, knowing that the time of his demise was drawing near. I was particularly moved by the one entitled Sabbath.

I am reminded of the words with which Walter Mondale eulogized Hubert Humphrey in 1978:

He taught us all how to hope and how to live, how to win and how to lose, he taught us how to live, and finally, he taught us how to die.

By the example of your grace and your courage, what a gift you have given us, Dr. Sacks.

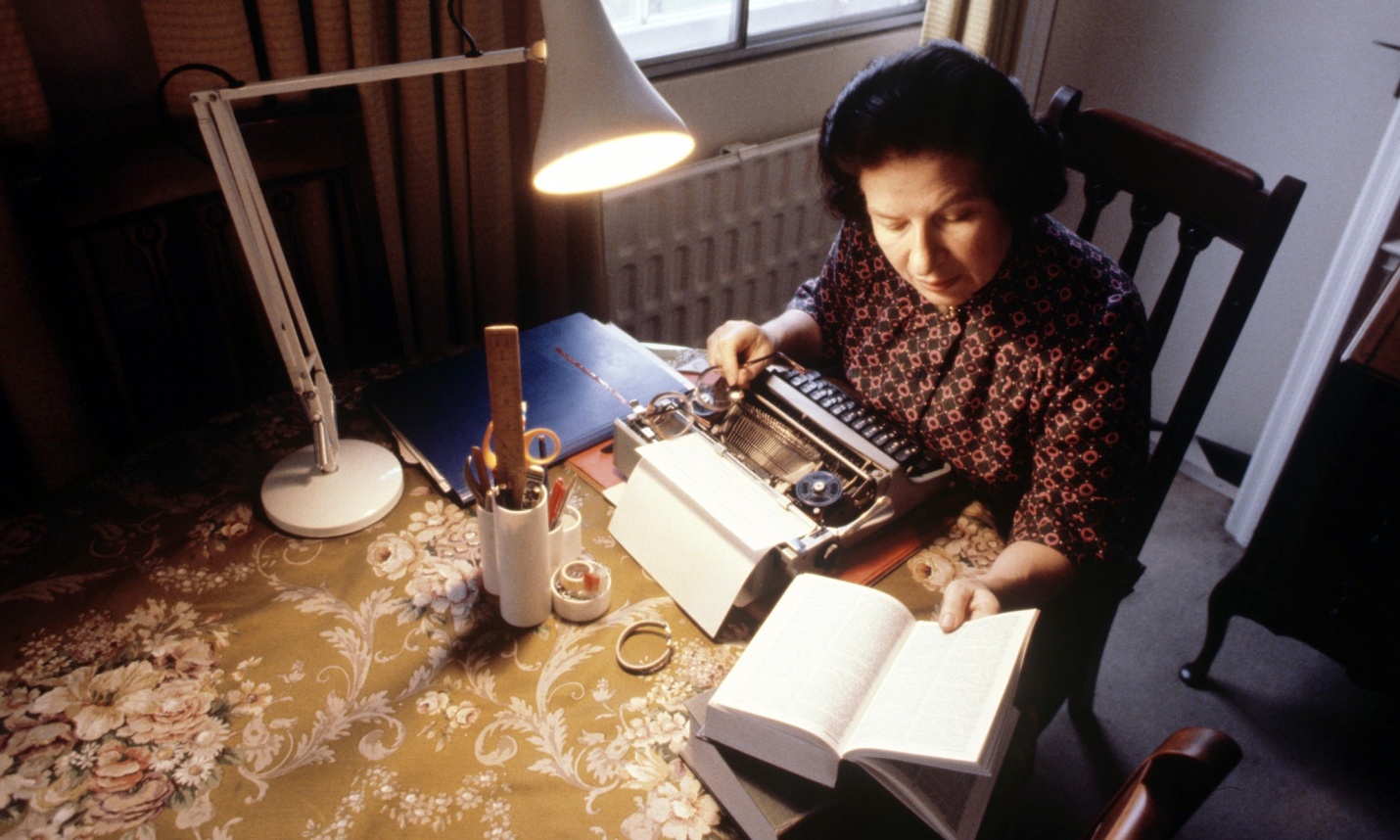

Ruth Rendell

Ruth Rendell and P.D. James

I didn’t know where to begin. But an article in the Guardian helped. It listed five key works by this author. They are as follows:

1. From Doon with Death (1964). Ruth Rendell’s first published novel. In it, she introduces her policeman protagonist Reginald Wexford.

2. A Judgement in Stone (1977). A standalone containing one of the best known opening sentences in modern crime fiction.

3. A Dark-Adapted Eye (1986). Winner of the 1987 Edgar Award for best mystery, this is the first work that Rendell published using the pseudonym (alternate identity?) of Barbara Vine. A book I’ve always meant to read and still haven’t.

4. Adam and Eve and Pinch Me (2001). This choice, another standalone, threw me. I know I read it, but I remember nothing about it. Time to revisit, I suppose.

5. Not in the Flesh (2007). A later Wexford, and one of the best in the series, in my view.

I think by “five key works,” authors Alison Flood and Vanessa Thorpe mean to suggest good entry points into Ruth Rendell’s large and varied body of work. Looking at this list, the one choice they made that I totally agree with is A Judgement in Stone. I’ve led book discussions on it, and I’ve read it three times. And every single time I’m filled with dread and awe, despite already knowing what the shattering climax will be. The build-up of tension over the course of the narrative is simply incredible.

For me, the Wexford novels, good from the very beginning, became increasingly compelling from the mid-1980s to the present. From An Unkindness of Ravens (1985) to No Man’s Nightingale (2013), I’ve loved them all. Somehow, when I’m reading them, my critical faculties are suspended. I’m held in the thrall by the writing, the story, the characters, Wexford and his utterly ordinary yet fascinating family life, his second in command Mike Burden, whose starchy, conservative exterior serves to protect the vulnerable man within.

I thought The Vault was an especially cunning work. It’s a sequel to A Sight for Sore Eyes, in which Rendell gave us one of the most uniquely frightening characters I’ve ever encountered in fiction: Teddy Brex. The Vault is a Wexford novel; A Sight for Sore Eyes was a standalone. In The Vault, Rendell brings in a retired Wexford to help investigate an extremely strange discovery: the remains of four bodies found in the sealed off basement of a house. If you’ve read A Sight for Eyes, you the reader have some recollection of who these people are. Wexford and company lack that advantage.

Houses are often fateful places in Rendell’s fiction; so it is with this one, named Orcadia Cottage.

The Girl Next Door, a standalone that came out last year, stands as a kind of summation of Rendell’s art. The vagaries and the irony of the human condition find rich embodiment in the cast of characters that people this narrative. I thought it was outstanding.

I’ll save my final words of praise for novel written in 1987 but not read by me until 2012: A Fatal Inversion. This is probably the most riveting and haunting work of psychological suspense that I’ve ever read. Read my review to find out why.

I’m running out of superlatives. I leave you with this insightful encomium by Val McDermid, as well as this gracious tribute from British Labour Party Leader Ed Miliband:

Ruth Rendell was an outstanding & hugely popular figure in British literature & served in the House of Lords with great loyalty & passion.

Oh – and the famous first line of A Judgement in Stone?

Eunice Parchman killed the Coverdale family because she could not read or write.

With the passing of P.D. James, the end of an era

The first Adam Dalgliesh novel I read was A Taste for Death, published in 1986. I remember little of the actual plot except for the crime described early on in the book. The author’s depiction is both shockingly out of place and totally bewildering. I was later to learn that James makes frequent use of this kind of scenario, to wit:

The first Adam Dalgliesh novel I read was A Taste for Death, published in 1986. I remember little of the actual plot except for the crime described early on in the book. The author’s depiction is both shockingly out of place and totally bewildering. I was later to learn that James makes frequent use of this kind of scenario, to wit:

I think it was W.H. Auden who said that there is the potential for more horror in that one single body on the drawing room floor than there is in a dozen bullet-riddled bodies down Raymond Chandler’s mean streets. That one body is out of place: It’s shocking because it’s in the wrong place. We don’t associate murder with the vicarage drawing room. I use that quite a lot, that contrast between the awfulness of the deed and perhaps the beauty of what’s surrounding it. We get it with the murder in Cambridge in high summer, in “An Unsuitable Job for a Woman.” We get the bodies in the church in “A Taste for Death,” brutally murdered in what is, after all, a holy place.

(from a 1998 Salon Magazine interview )

Here is the actual quote from W.H. Auden’s 1948 essay, “The Guilty Vicarage:”

In the detective story, as in its mirror image, the Quest for the Grail, maps (the ritual of space) and timetables (the ritual of time) are desirable. Nature should reflect its human inhabitants, i.e., it should be the Great Good Place; for the more Eden-like it is, the greater the contradiction of murder. The country is preferable to the town, a well-to-do neighborhood (but not too well-to-do-or there will be a suspicion of ill-gotten gains) better than a slum. The corpse must shock not only because it is a corpse but also because, even for a corpse, it is shockingly out of place, as when a dog makes a mess on a drawing room carpet.

In a 2012 interview with The Guardian, mention is made of the possibility of W. H. Auden writing some verse especially for James to insert into one of her novels, attributing it to her poet/detective Adam Dalgliesh. The idea never bore fruit, though James notes with justifiable pride that “Auden loved detective stories – he always read my books.”

The other thing I remember from that reading of A Taste for Death is more subtle. I’d describe it as the sense of something more elemental at work in the pages of the novel, a deeper quest into the very essence of human nature. In other words, the mystery was eventually solved, but not the Mystery. (I encountered similar elements in The Pale Horse by Agatha Christie. In Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks, Christie scholar John Curran says of this novel that it evokes “……a genuine feeling of menace over and above the usual whodunit element.”)

At any rate, we who love crime fiction owe a debt of gratitude to P.D. James, a writer whose elegant style, masterful storytelling, and singular characters have for decades kept us engrossed, entertained, and edified. It was a life well lived, and a body of work that will stand the test of time.

A mist lay over the valley, so that the rounded hilltops looked like islands in a pale-silver sea. It had been a clear and cold night. The grass on the narrow stretch of lawn under her windows was pale and stiffened by frost, but already the misty sun was beginning to green and soften it. On the high twigs of a leaf-denuded oak three rooks were perched, unusually silent and motionless, like carefully placed black portents. Below stretched a lime avenue which led to a stone wall, and beyond it a small circle of stones. At first only the tops of the stones were visible, but as she watched, the mist rose and the circle became complete. At this distance, and with the ring partly obscured by the wall, she could see only that the stones were of different sizes, crude misshapen lumps around a central, taller stone.

(from The Private Patient)

Among my favorites:

Ave atque vale, Baroness James . You will be sorely missed.

Tom Clancy

No one could be immersed in the world of popular fiction in 1984 and not be impressed by Tom Clancy’s sensational entry into the field. With The Hunt for Red October, he virtually invented the subgenre of techno-thriller.

At that time, I had been working at the library for only two years, and I well remember the heavy demand for that title. Our patrons were especially intrigued by the fact that Clancy was something of a local celebrity, hailing as he did from Calvert County in Southern Maryland.

Here are two articles from the Washington Post about Mr. Clancy, one by Emily Langer and the other by Dennis Drabelle.

Here are two articles from the Washington Post about Mr. Clancy, one by Emily Langer and the other by Dennis Drabelle.