Hercule Poirot: The question is, can Hercule Poirot possibly by wrong?

Mrs. Lorrimer: No one can always be right.

Hercule Poirot: But I am! Always I am right. It is so invariable it startles me. And now it looks very much as though I may be wrong, and that upsets me. But I should not be upset, because I am right. I must be right because I am never wrong.

Visuals relating to The Girl of His Dreams, by Donna Leon

Madonna with Child, Giovanni Bellini ca 1485.

Stolen – for the third time! – in 1993; present whereabouts unknown p. 9

Palazzo Mocenigo, mentioned on p. 100. It’s now a museum. See Lucia: A Venetian Life in the Age of Napoleon, by Andrea Di Robilant

These images have been assembled as part of the preparation for a book group discussion. I have also reviewed The Girl of His Dreams in this space.

Quick and easy ways to get title suggestions (but is this really what some of us need?)

We owe businessman Herbert Simon a debt of gratitude for saving Kirkus Reviews – now officially Kirkus Media – from extinction. This invaluable reviewing organ was slated for closure when Mr. Simon purchased it in 2010. Kirkus’s reinvention for the digital era has been most felicitous. I well remember reading the rather dour print version at the library. Still, even then, it was a great source of book reviews.

Now, however, it has gained added value as an online entity. It is eminently searchable. Its starred reviews are a reliable guide to works that will be worth your while (reliable – not foolproof). Kirkus also offers help for aspiring writers; it has even established a prize award of its own. (Do we actually need another book prize? Oh heck – why not?)

I use Kirkus primarily for its starred mystery reviews. But there’s lots more rich content for book lovers available on its site.

Another terrific media review source is Booklist Magazine, a publication of the American Library Association. While certain of Booklist’s content resides behind a pay wall, reviews for the current year are freely available. I use this source for mystery reviews, and also for reviews of new nonfiction. (Scroll down to below “Find Best Books of 2015” to access this content.) Both Kirkus and Booklist have been used in the past as selection tools for libraries and bookstores. I’m not certain if they still are.

A brief aside regarding nonfiction, where there has been so much interesting writing happening lately that I’ve pretty much fallen hopelessly behind. I am currently – or I should say, concurrently – reading these titles:

and finally, I’m about to finish, with great regret:

and finally, I’m about to finish, with great regret:  . Murder by Candlelight is not only a true crime narrative – or rather, a narrative of multiple true crimes – it is a work of philosophy, psychology, and history. True, some of it is hard to read – repugnant, even gruesome – but other parts are rich with a profound insight into the human condition. The erudition displayed by Michael Knox Beran is nothing short of amazing. For instance, it is not every day that a book sends me scurrying to the works of Arthur Schopenhauer:

. Murder by Candlelight is not only a true crime narrative – or rather, a narrative of multiple true crimes – it is a work of philosophy, psychology, and history. True, some of it is hard to read – repugnant, even gruesome – but other parts are rich with a profound insight into the human condition. The erudition displayed by Michael Knox Beran is nothing short of amazing. For instance, it is not every day that a book sends me scurrying to the works of Arthur Schopenhauer:

Yes, I know, he doesn’t look as though he’d be very scintillating at a dinner party, but he’s actually a deeply fascinating thinker. I have in mind specifically a work entitled The World as Will and Representation. Sound dry as dust? Not the portions quoted in Murder by Candlelight – they’re anything but.

I had not previously heard of Michael Knox Beran, but he will most definitely be getting a fan letter from Yours Truly.

In searching for more historical true crime following my rueful withdrawal from Beran’s book, I stumbled upon a portion of the MWA‘s Edgar site that I’d not seen before. It is a list of submissions from publishers for consideration for next year’s Edgar Awards. These are suggestions, not selections. Those will be announced on or around January 19, Edgar Allan Poe’s birthday. (And Poe Toaster, we beg you to come back this year!)

As you will see, the list of mysteries is already very long. The list of true crime titles – or in MWA parlance “Fact Crime” – is considerably shorter and thus easier to digest.

Tchaikovsky and more: a concert you won’t want to miss

On October 7, Carnegie Hall opened its 2015-2016 with a concert featuring the New York Philharmonic led by music director Alan Gilbert. The program opened with the world premiere of Vivo, a piece by Finnish composer Magnus Lindberg. (The shade of Sibelius, Lindberg’s countryman, must be rejoicing!) This was followed by Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto and Daphnis and Chloe Suite No. 2 by Maurice Ravel.

A marvelous program, to be sure. I’ve long loved the Ravel work, a masterpiece of moody evocation. As for the Tchaikovsky, I hadn’t listened to it – really listened to it – for a long time. He’s one of my favorite composers, but in recent years, I’ve been immersed in the symphonies and orchestral suites, worked I can listen to again and again and be thrilled every time.

For those of us of my generation, the Piano Concerto No. 1 will always stir memories of Van Cliburn’s stunning victory at the 1958 International Piano Competition in Moscow. At the height of the Cold War, a gangly Texan brought the trophy home to the U.S. He was given a ticker tape parade down Broadway, the only classical musician ever to be so honored.

RCA Victor signed him to an exclusive contract, and his subsequent recording of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 became the first classical album to go platinum. It was the best-selling classical album in the world for more than a decade, eventually going triple-platinum. Cliburn won the 1958 Grammy Award for Best Classical Performance for this recording. In 2004, this recording was re-mastered from the original studio analogue tapes, and released on a Super Audio CD.

[from the Wikipedia entry]

My parents owned this album, as did many of my friends.

Carnegie Hall is currently celebrating its 125th anniversary. Peter Tchaikovsky himself traveled from Russia to New York City for the opening of the Hall in 1891. Among the works he conducted on that occasion was the Piano Concerto No. 1.

Last Wednesday night, the soloist was Evgeny Kissin. You can judge for yourself how terrific this performance was. I’ve watched it at least four times, and it gives me chills every time. I’ve not been able to get the music out of my head. Intense lyricism and masterful orchestration combine to create a work of transcendent power.

As for Kissin – in the New York Times review, Anthony Tommasini comments:

Mr. Kissin, who turns 44 on Saturday, has been playing Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto since his teens. Yet the hallmark of this performance was the searching curiosity he conveyed throughout. Taking a somewhat spacious tempo in the well-known opening section of the first movement, with its soaring melody and resounding piano chords, Mr. Kissin emphasized its majesty and lyricism. Not surprisingly, this consummate virtuoso effortlessly dispatched the difficulties of the piece — the arm-blurring bursts of octaves, spiraling flights of finger-twisting passagework and more.

“Arm-blurring bursts” indeed – he was a marvel!

I would watch this video sooner rather than later. I’m not sure how long it will be available online in its entirety. If you’re pressed for time, watch the Tchaikovsky, If you’re even more pressed for time, watch the Third and final movement of the concerto.

Follow this link to the video.

“Did ever raven sing so like a lark, / That gives sweet tidings of the sun’s uprise?” Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus

In John Lister-Kaye’s Gods of the Morning, these lines appear above the chapter entitled, “The Gods of High Places” (chapter 8).

In John Lister-Kaye’s Gods of the Morning, these lines appear above the chapter entitled, “The Gods of High Places” (chapter 8).

Lister-Kaye – i.e. Sir John Philip Lister Lister-Kaye, 8th Baronet OBE – is inordinately fond of crows, rooks, ravens – those avian species subsumed under the genus Corvus. He studies them at Aigas, the Field Study Center in the Scottish Highlands which he founded in 1977. He lives and works there; it is his calling and his life’s work. What a lucky man! (You can read in the Wikipedia entry how he made this “luck” happen.)

There is nothing dull about a raven. As glossy as a midnight puddle, bigger than a buzzard, with a bill like a poleaxe and the eyes of an eagle, its brain is as sharp and quick as a whiplash. Surfing the high mountain winds, ravens tumble with the ease and grace of trapeze artists, and their basso profondo calls are sonorous, rich and resonant, gifting portent to the solemn gods of high places. Ravens surround us at Aigas, and they nest early.

Most of us consider crows a sort of nuisance bird, and anyway too common to be of any great interest. Lister-Kaye gently seeks to disabuse us of that notion.

The advent of wildlife tourism as an economic force, legal protection and a wider conservation understanding has permitted raven numbers to increase and the birds to nest at least in some areas, unmolested. They are now part of our daily lives. I listen out for the guttural ‘cronk, cronk’ as they pass overhead every day. If a solitary black bird rows into view (rooks are almost never solitary), I stop what I’m doing to look for the wedge-shaped tail or to get the measure of its bulk to distinguish it from carrion or hooded crows. As the years have flicked by, their daily appearance here, their criss-crossing of the glen from high moor to hill, has become predictable, a reassuring norm, something we note with pleasure, and a characterful addition to our resident avifauna.

Confident of that interest, as a chunky silhouette crosses or that unmistakable plunking call reverberates from the woods, I don’t hesitate to point and call to my friends and field centre colleagues, ‘Ha! Raven!’, yet I find myself still wary of my audience. Those farmers and crofters aplenty who charge ravens with killing lambs and many, not just old-school, gamekeepers are quick to condemn all crows, but especially hoodies and ravens, and will still do their utmost to kill them. ‘The croaking raven doth bellow for revenge.’ (Hamlet, Act III, scene ii.)

As you’ve already no doubt noted, Shakespeare makes frequent mention of the raven. My favorite instance of this occurs in MacBeth, when Lady MacBeth gives vent to her ghoulish pleasure at Duncan’s arrival:

The raven himself is hoarseThat croaks the fatal entrance of DuncanUnder my battlements.

I’ll close with a photo taken by my son Ben Davis at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, a nature lover’s paradise that probably has some aspects in common with the Aigas Field Centre.

[Click to enlarge]

With A Possibility of Violence, the certainty of a great discussion (accompanied by some brief detective digressions)

On Tuesday, the Usual Suspects enjoyed an exceptionally bracing discussion. D.A. Mishani’s A Possibility of Violence lent itself to analysis on many levels. In fact, the very issue of its Israeli setting and Hebrew language authorship got us going in a variety of different directions.

On Tuesday, the Usual Suspects enjoyed an exceptionally bracing discussion. D.A. Mishani’s A Possibility of Violence lent itself to analysis on many levels. In fact, the very issue of its Israeli setting and Hebrew language authorship got us going in a variety of different directions.

This title being Pauline’s choice, she gave us some very interesting background on contemporary Israel in general and the Israeli police in particular. It seems that until recently this force was given scant respect by the public. This was partly due to the fact that a majority of its members are drawn from the Sephardic or the Mizrachi communities. This prompted a need for clarification of those terms, along with the term Ashkenazi, for those who were not familiar with them. (Useful elucidation can be found on the site My Jewish Learning.)

Dror Mishani was working on a doctoral dissertation at Cambridge when he met his wife, who was teaching there. Somehow the dissertation never got written. But The Missing File, first entry in the Inspector Avraham Avraham series, did. (Our book, A Possibility of Violence, is second.) Both titles have been well received by critics and readers alike – with good reason, most (but not all) of us thought. Mishani, a lifelong lover of crime fiction, is on the Humanities faculty of the University of Tel Aviv.

In this interview with Lidia Jean Kott of NPR, Mishani explains among other points why there’s such a paucity of Israeli mystery writers.

Our discussion was so lively and wide ranging, it took some doing to get us focused on the novel. Pauline had prepared discussion questions for us. With one of them, we were asked whether A Possibility of Violence was more plot driven or character driven? Or was it both? I can’t recall what was concluded by the group, but for myself, I believe it was both, and that was one of the novel’s primary strengths.

The story begins with the discovery of an unattended suitcase left outside a day care facility. A man named Chaim Sara has a son enrolled there. In addition, he has an older son in grammar school. There is a mystery about the Sara family: the children’s mother, Chaim’s wife Jenny, a Philippine national, is not living with them. Chaim claims that she has gone back to her native country to attend to her sick father. But something about his story does not ring true.

*************************************

An aside at this point: people had difficulty pronouncing the name ‘Chaim.’ The guttural sound at the beginning was the main problem. There is no equivalent for it in English. Later, I recalled that in the past, that sound was rendered as the letter ‘h,’ rather than ‘ch.’ I was also thinking that if the speaker has any familiarity with the French, German, or Russian languages, he or she has a better chance of being able to produce that guttural.

At any rate, here’s a little YouTube snippet to help out:

(He sounds rather tragic, don’t you think?)

*****************************

The depiction of Chaim Sara, we agreed, is one of this novel’s most impressive achievements. One cannot help but care about him and feel anxiety about his fate. At the same time, the reader yearns to penetrate his secret. And all this time, his fierce devotion to his sons is bodied forth as the most basic aspect of his existence.

This fact makes it all the vexing that Avi – Avraham Avraham – catches hold of the wrong end of the stick where Chaim is concerned and simply won’t let go until he’s forced to. But there’s a reason for this, and it has to do with a previous case as set forth in The Missing File, the first book in the series. It’s a reason, but it does not excuse Avi’s wrongheadedness. Some in the group understandably disliked him for it and douted his abilities as a detective. We did agree that he is made in the mold of the doubting policeman, who lacks complete confidence in himself. In addition, he is deeply anxious concerning an uncertain element in his personal life: his love for Marianka, a police detective in Belgium. Will this relationship achieve the fruition he so earnestly desires?

This is one of my favorite from among Pauline’s excellent discussion questions: “Is it more satisfying to read about such a flawed investigator or do you prefer a more competent detective such as Montalbano, Brunetti, Maigret, Poirot, etc.?” She then adds: “None of these examples seems to suffer from self-doubt.”

That was enjoyable concept to kick around for a while! (I couldn’t help suggesting that Reg Wexford be added to the list.) A post I did in 2007 entitled The fictional British policeman, in all his (or her) vulnerable glory may be of interest in this context.

Upon second thought, I think there’s something of a continuum here. At one end of the spectrum, the Crown Prince of Rectitude has got to be Hercule Poirot. Here is but one instance of many, from Cards on the Table:

Maigret does proceed with a slow and quiet assurance that rarely admits of a major gaffe. Brunetti and Wexford, I think, are somewhat more tentative in their intuitions and actions. All three possess the distinct advantage of having supportive and empathetic spouses. (I’m not sufficiently well read in the Montalbano books to comment one way or the other.)

Well, this is a bit of a digression, but the discussion itself was filled with them. (At one point, Frances spoke of the pleasure she derives from these “beside the point” yet provocative meanderings.)

In an interview in Krimi-Couch, an online German mystery magazine, Mishani states:

I’m not trying to write a page-turner, I’m trying to write literature, using the detective genre. So for me, a literary crime novel is a novel about crime, but not only about crime (it is also about society, about language, about literature, about the genre itself etc …)

Pauline shared this quote with us, and then asked us to comment on whether we thought Mishani had achieved this goal in A Possibility of Violence. Naturally the question arose as to what criteria we would apply in this instance. How was the quality of the writing and, by implication, the translation? Were larger themes bodied forth in the narrative? Did the author manage to advance the story according to the maxim, Show, Don’t Tell? Were the motivations of the main characters credible? Was the psychology of the main characters set forth in a believable way? Did the logistics of the plot make sense?

I’m not sure whether we reached a consensus. Some of us had been hoping that more of the sights and sounds of Israel would be featured in the book. On the other hand, the writing was generally praised. It was felt by most, if not quite all of us, that the characters were consistent, believable, and – most important – interesting. Frank was especially impressed by how Mishani generated suspense consistently throughout the novel. He did this through the characters’ distinct personalities, particularly that of Chaim Sara. (Of late, Frank’s writerly perspective has added greatly to our discussions.)

Pauline provided us with the names of some other authors who take as their subject Israel or Palestine. (There are others, but they’ve not yet been translated into English):

Batya Gur

Jon Land

Matt Beynon Rees

Robert Rosenberg

Liad Shoham

Before the meeting, she had sent us a link to an article called Reading Israel. Also, it turns out that the Washington DC Jewish Community Center is hosting a Jewish Literary Festival from the 18th to the 28th. Some of the participating writers are David Bezmozgis, Etgar Keret, Laura Vapnyar, and Michael Pollan.

Pauline has a friend who has met Dror Mishani. She asked her friend to e-mail him and ask when his next Avraham Avraham novel will be available for English speakers to read. He responded that it should be out in a few months and that he’s currently reviewing the translation. The book’s title is The Man Who Wanted To Know. As for us, we’re the book group that wants to know! I think most of us plan to read it when it becomes available.

Pauline’s friend also found out that Mishani is currently in the U.S. teaching at the University of Massachusetts until January, at which time he will probably be relieved to be departing New England’s notorious winter for the warmer climes of the Middle East. He expressed himself happy and willing to talk to our group if we’re close by. Louise immediately suggested a field trip!

We agreed that this series would be great for television. We’ve now got detectives from Sweden, Italy, France, and doubtless other countries on the small screen. Come on, Israel! This could be your moment.

***********************************

I have no doubt that I’ve omitted plenty and possibly made some errors. Therefore: corrections, questions, comments, and clarifications are all welcome, either here on WordPress or via Facebook.

Two happenings that make me (cautiously) hopeful

Lately, there’s been so much in the news that’s appalling and heartbreaking; I wanted to offer two items as harbingers, however small, of hope.

First: the Rajko Orchestra performing Bela Bartok’s Romanian Dances. The YouTube post describes the venue as a synagogue in Budapest; the year is given as 2004.

*******************************

Second: a while back, in Chicago, my son Ben and I were watching my granddaughter Etta at soccer practice:

I think that’s Etta, foreground left, with the braids. You’ll understand that the scene was quite kinetic, so I can’t be sure.

Meanwhile, Ben had struck up a conversation with another Dad. When he realized he hadn’t introduced himself, he did so, with an extended hand:

Hi, I’m Ben.

The other extended his hand also, smiled, and responded:

Hi, I’m Mohamed.

I remember thinking immediately, This is one of the (many) reasons that I, granddaughter of immigrants. love this country.

Farewell to Henning Mankell, crime fiction sage of the north country

Yesterday, I was saddened by news of the passing of Henning Mankell. I’ve enjoyed his crime fiction a great deal. The first Kurt Wallander novel I read was One Step Behind; from that moment, I knew I’d be reading more. (Among other things, Wallander was struggling with Type Two Diabetes, just as I was. So I guess that helped me to bond with this character.) Other Kurt Wallander novels I’ve read and greatly liked by Mankell are The Dogs of Riga and Firewall. In 2009 (2011 in this country), Mankell closed this series out with The Troubled Man, a real tour de force, in my opinion.

I also read Before the Frost, in which Wallander’s daughter Linda takes center stage. Mankell had intended to continue with this series, but a tragedy intervened that it made it impossible for him to write any more novels featuring Linda Wallander. Click here to read more about what happened.

I also read Before the Frost, in which Wallander’s daughter Linda takes center stage. Mankell had intended to continue with this series, but a tragedy intervened that it made it impossible for him to write any more novels featuring Linda Wallander. Click here to read more about what happened.

Stieg Larsson, author of the Dragon Tattoo novels featuring the memorable Lisbeth Salander, is often given credit for initiating a second Golden Age in Swedish crime fiction. (The first began with the great creative team of Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, whose Martin Beck series dates from 1965 to 1975.) There’s no getting around the sensation caused by Larsson‘s singular and highly original creation, but Henning Mankell also deserves credit for once again focusing the spotlight on the masterful mysteries issuing from his native land.

I regret that there will be no further insightful, ruminative prose issuing from his pen.

A most wondrous tome currently resides on my coffee table…

Martin Salisbury is a professor of illustration at the Cambridge School of Art of Anglia Ruskin University. He obviously has a deep knowledge of children’s literature, and an equally deep love for it. His perspective is refreshingly international.

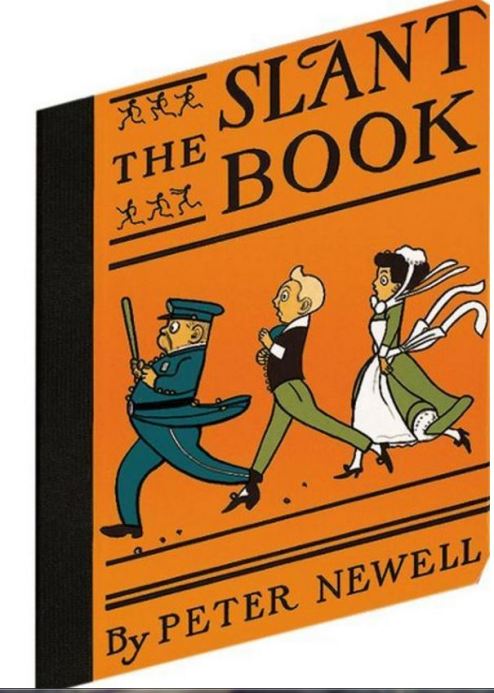

Salisbury begins his survey with a 1910 title: The Slant Book by Peter Newell.

The book is rhomboid in shape,with text on the verso page and image on the recto throughout. The story follows the chaos of a runaway baby’s buggy as it rolls down a hill, the gradient of which is exactly equal to the slope of the book, so that the delighted baby is seen to be rolling towards the gutter of the book on each double-page spread.

(Martin Salisbury’s description)

Click here for a look inside The Slant Book.

As I make my enraptured way through this book, I’ve encountered some old friends  but quite a few more that I’d never heard of. And when I came to Village and Town by S.R. Badmin (London, 1942), I was literally stopped in my tracks, my Anglophile antennae quivering madly!

but quite a few more that I’d never heard of. And when I came to Village and Town by S.R. Badmin (London, 1942), I was literally stopped in my tracks, my Anglophile antennae quivering madly!

I had to have this one! It was then that I learned my first lesson about acquiring older, out of print children’s picture books: They can be rare. And they can be expensive. Persistence paid off in this instance, I’m glad to report. For what I judge to be a reasonable sum, Village and Town is on its way to me courtesy of Abebooks’s UK site.

I am not at all knowledgeable in this field, but I’ve felt for quite some time that some of the greatest art being made anywhere can be found in children’s picture books. If you love brilliant colors

and great draftsmanship, you will find these in abundance in the many great children’s picture books.

***********************

If you’d like some names and titles of recent picture books that have won critical acclaim, have a look at the list of Caldecott Medal Winners and Honor books. A great source for children’s literature in general is Barb Langridge’s site A Book and a Hug.

Where this vast subject is concerned, I’ve only scratched the surface in this post. My main purpose was to alert people to Martin Salisbury’s outstanding work of scholarship in this field; 100 Great Children’s Picture Books is a joy!