Latest entries in three long running mystery series of which I am inordinately fond (good grief…)

Well, gosh, I can hardly believe that we’re already up to Number 27 in the Inspector Banks series. It seems like only yesterday when the first in the series, Gallows View (1987), came out. My library buddy Marge and I scarfed it up at once, and have remained more or less faithful throughout. A glance at the listing on the StopYoureKillingMe site shows the accolades this series has deservedly garnered.

So – What about this one? The dual plots involve the shady dealings of a developer and the disappearance of Ray Cabbot’s lover Zelda. (Ray is the father of Banks’s colleague Annie Cabbot.) Of the two, the latter is the more compelling. It’s overall a reliably good yarn, especially for those of us who have been hanging out with Banks and his circle for over two decades. We’re updated on his family news, and as usual, his amazingly wide ranging musical tastes are precisely noted, as in this sentence:

The Bach finished, and Banks switched to Xuefei Yang playing music by Debussy, Satie, and others arranged for guitar.

This latter is of particular interest, as he’s trying to learn to play that instrument, with a little help from his rock musician son Brian.

Not spectacular, but enjoyable and involving nonetheless.

*******************

Reading the Guido Brunetti novels is, for me, a situation similar to what I described above regarding the Alan Banks books. And this is an even longer running series: Transient Desires is number 30!

I recall how back in the 1990s, we had difficulty getting these books. They were coming to us from overseas – Donna Leon was at the time living in Venice – and they arrived here erratically and in no particular order. U.S. publishers didn’t think they’d be of interest to American readers. A police procedural set in Venice? A detective who’s a totally straight arrow and a devoted family man to boot? Who wants to read that?

We do. Especially when the novels are so beautifully written and so artfully conceived.

Anyway, I thought this entry was an especially good one. One night, two young men in a motorboat leave two even younger American tourists, who have been badly injured, at the docking area of a hospital. The men then flee before anyone can note their identity. It’s a good example of a case that seems to be about one thing, but turns out to be about something else entirely.

Meanwhile, we get lovely scenes of the Brunetti family dining together and having lively discussions on a variety of subjects. Guido and Paola’s offspring, Chiara and Raffi, are approaching adulthood, seemingly with the same effortless grace and integrity they’ve observed over the years in their parents.

And Venice, that troubled and glorious place, is, as always, like a character in the narrative, in and of itself – a marvelous and mysterious entity. (I highly recommend the Smithsonian Associates webinar Venice: 1000 Years of History.)

***************************

What great TV the Bill Slider series would make. They could lift the dialog right from the books themselves.

Some examples:

Slider and his partner Atherton are searching the house of a murder victim. Eric Lingoss, a personal trainer, was a health nut as well as a fitness fanatic. At one point, while rummaging through rummaging through Lingoss’s cabinets, a container of Omega Three supplement falls out and lands on Atherton’s head. This exchange follows, initiated by Slider’s inquiry:

“Are you hurt?”

“Super fish oil injuries. The man’s a health nut.”

“The body is a temple,” Slider reminded him.

“Up to a point. Let he who is without sin bore the pants off everyone else.”

And later, this:

“Did you know,” said Atherton, as they turned into Lime Grove, “that A Tale of Two Cities was first serialized in two English newspapers?”

“Really? Which ones?”

It was the Bicester Times, it was the Worcester Times.”

This exchange prompts an inquiry about Atherton’s Significant Other, who’s currently out of town:

Slider looked at him. “When is Emily coming back?”

“Sunday. Why?”

“You need someone to take the edge off you.”

You don’t understand what it’s like, having curatorship of a magnificent brain,” Atherton complained.

Well, none of this is very serious, but it is fun to read. Cynthia Harrod-Eagles is famously fond of puns and other forms of humor. Though every shot doesn’t hit the mark, enough off them do so that the reader is given plenty to smile about.

This series features a long story arc involving Slider’s personal life, so it’s advisable to being at the beginning. (Orchestrated Death is the first.) Current wife Joanna, an orchestral violinist, is in the final stages of pregnancy. Inevitably, the novel concludes with the birth of their second child, a daughter. Slider has two older children from his first marriage, so it’s all very modern, and a lot of fun to follow.

Oh, and the investigation is interesting, too, tougher than usual and all the more satisfying when it’s successfully resolved.

Art Certificate Earned!! :))

I got it! And I’d like to share with you just a small fragment of my delightful experience in getting there.

Art historian Rocky Ruggiero presented two four session courses this Spring for the Smithsonian: Italian Renaissance Art and Drama Most Splendid: The Art and Architecture of the Baroque and Rococo. I want to briefly talk about the Italian Renaissance course first.

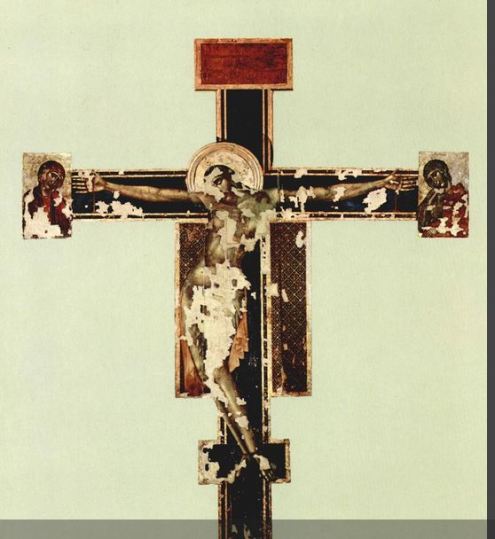

Professor Ruggiero gave us a quick survey of late Medieval Art, after which we slid easily into the early Renaissance. First, Cimabue (c. 1240 – 1302), whose famous Crucifix was so badly damaged in the 1966 flood in Florence. It took them eleven years to restore it.

Today in Florence, priceless artworks or manuscripts are not kept at street level or underground. Higher flood barriers are in place near the Uffizi Gallery; new reservoirs and another dam were built. Regular flood drills are conducted in the city, and advance warning systems are in place, yet some experts question whether enough has been done to prevent disaster next time the Arno bursts its banks.

Cimabue’s Crucifix is now fixed on a high wall in the Museum of Santa Croce, with an electrical pulley designed to haul it up to safety in the event of another deluge.

[From “The Great Flood of Florence, 50 Years On,” by Eileen Horne, in The Guardian, November 5, 2016]

There’s a terrific book on this subject by Robert Clark: Dark Water: Art, Disaster, and Redemption in Florence.

Anyhow, after a necessarily brief stop in Siena, highlighting the work of two of its great masters, Giovanni di Paolo and Duccio di Buoninsegna,

Detail of the above:

Duccio’s spectacular Maesta. I love the story of how the people carried this masterpiece through the streets of the city before placing it on the altar of Siena Cathedral. I can almost see the procession, in my mind’s eye…

it was back to Florence, Cradle of the Renaissance. But wait – There’s still Pisa, a place which as lots more to see than this:

Nicola Pisano and Giovanni Pisano, equally gifted father and son, created these beautiful sculptural works:

So when we finally get back to Florence, we must immediately salute the mighty triumvirate of the Italian High Renaissance: Raphael, Leonardo, and Michelangelo.

Of the three, Raphael is my personal favorite. I love his portrait pf Baldassare Castiglione:

Also I like this video, with its dramatic re-enactments and its appealing actor, Joe McFadden, in the role of Raphael:

I can never forget standing, alongside my sister-in-law Donna, before Leonardo’s Madonna of the Rocks in London’s National Gallery:

Finally, Michelangelo. Professor Ruggiero waxed rhapsodic over this genius, of course with good reason:

Professor Ruggiero stated most emphatically that Michelangelo did NOT assume a prone position while painting the Sistine ceiling. He painted standing up, on the scaffolding.

This is such a quick run-though, with so much left out – sorry! Also, I hope I haven’t made any errors – let me know if you spot any.

And I didn’t even get to “Drama Most Splendid.” Next time, then.

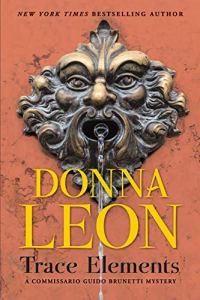

‘…gossip and insinuation, those Venetian twins of truth.” – Trace Elements by Donna Leon

I enjoyed the latest novel by Donna Leon, as I knew I would. In this one, the police are dealing with some chronic pickpockets; they are caught, punished, and then go on plying their trade as before. A more serious case involves a dying woman, Benedetta Toso, whose husband was recently killed in a motorcycle accident. She has expressed an urgent need to talk to the police about what happened to her husband.

I enjoyed the latest novel by Donna Leon, as I knew I would. In this one, the police are dealing with some chronic pickpockets; they are caught, punished, and then go on plying their trade as before. A more serious case involves a dying woman, Benedetta Toso, whose husband was recently killed in a motorcycle accident. She has expressed an urgent need to talk to the police about what happened to her husband.

Commissario Guido Brunetti and his colleague Commissario Claudia Griffoni go to the hospice where Signora Toso is currently being cared for, in order to hear what she has to say. But she is only able to gasp out a few words before she too is overtaken by death.

Being present at the passing of the Signora is emotionally devastating for both Brunetti and Griffoni. It strengthens their resolve to work jointly to get to the bottom of the case.

Once again, the city of Venice gleams in the prose of Donna Leon. I would have liked to spend more time with Brunetti’s family: his children, Raffi and Chiara, who are fast leaving childhood behind, and his wife, the fiery and uncompromising Paola, a professor of English who has a highly laudable specialty in the novels of Henry James.

Nevertheless, a most enjoyable read. Leon’s writing is a joy, filled as it is with classical allusions:

Like Nausicaa listening at her father’s court to Ulysses’ account of his travels, Signorina Elettra sat enthralled.

Last year, Donna Leon was interviewed in the New York Times Book Review’s feature ‘By the Book.’ When asked how she first got hooked on crime fiction, she said this:

Ross Macdonald impressed me for the quality and beauty of his writing. I still, reading through them, come upon passages, especially his descriptions of characters, that I wish I had the courage to steal. He’s also a master at the well-honed plot that takes Lew Archer, and thus the reader, back a generation to find the source of the crime. He’s compassionate, apparently well read, and decent.

I was, of course, no end pleased by this. It’s most gratifying when the writers you esteem praise one another.

Donna Leon is 78 years old or thereabouts; she now divides her time between Venice and Switzerland. I wish her well, and of course I look forward to more novels featuring the investigations of Commissario Guido Brunetti.

Italy, mourning but resolute

On March 31, at noon, Mayor of Florence, Dario Nardella, lowered the flags at the Palazzo Vecchio to half mast. The mayor stood alone in piazza della Signoria as the whole of Italy observes a minute’s silence to remember those who have lost their lives to Covid-19, to pay tribute to the country’s medics and to look together to the future.

From The Florentine

Mysteries: from India to Italy in one enriching leap

In February, Marge led the Usual Suspects in a discussion of A Rising Man by Abir Mukherjee. This is the initial entry in a series set in post-World-War-One India, and it’s a great example of a first time author who hit the ground running. Beautifully written, this novel takes full advantage of its exotic setting, all the while weaving a tale of intrigue and introducing us to a memorable cast of characters. Chief among these is Captain Sam Wyndham, veteran of the Great War, who has been recruited to serve in the police force of India’s British Raj. His Sergeant is Surendranath Banerjee, called ‘Surrender-not’ because Sam and others have trouble pronouncing his name. (At any rate, it proves an apt nickname; he does not surrender to difficulty easily but is persistent and resourceful, and a great help to Sam.)

In February, Marge led the Usual Suspects in a discussion of A Rising Man by Abir Mukherjee. This is the initial entry in a series set in post-World-War-One India, and it’s a great example of a first time author who hit the ground running. Beautifully written, this novel takes full advantage of its exotic setting, all the while weaving a tale of intrigue and introducing us to a memorable cast of characters. Chief among these is Captain Sam Wyndham, veteran of the Great War, who has been recruited to serve in the police force of India’s British Raj. His Sergeant is Surendranath Banerjee, called ‘Surrender-not’ because Sam and others have trouble pronouncing his name. (At any rate, it proves an apt nickname; he does not surrender to difficulty easily but is persistent and resourceful, and a great help to Sam.)

Oh, and there’s a love interest for Sam. I just finished the second book, A Necessary Evil – also excellent – and all I have to say is, Make your wishes known, Sam, for heaven’s sake! Remember: He who hesitates….

Oh, and there’s a love interest for Sam. I just finished the second book, A Necessary Evil – also excellent – and all I have to say is, Make your wishes known, Sam, for heaven’s sake! Remember: He who hesitates….

Meanwhile, tensions between the Indians and their British overlords are portrayed with blunt realism. Even back then – undoubtedly before then – Indians were agitating for independence. Reading about the attitude of the British toward the native population, it’s no wonder. Enough to make you seethe with indignation, on their behalf.

Yet amidst all the turmoil, the allure of the place persists. From A Necessary Evil:

We left him and followed Sayeed Ali along a corridor whose walls were lined with murals that wouldn’t have looked out of place in the Kama Sutra, and into a cloistered courtyard dominated by a huge banyan tree….We walked through another arched doorway into a stairwell, climbing two flights before entering a well-apportioned sunlit apartment. The room was divided by a carved teak screen peppered with small holes. In front of the screen, the marble floor was covered with a black and gold Persian rug, strewn with silk cushions.

There are those who maintain that this sort of meticulous description does not belong in crime fiction. I for one love it.

Banyan trees, by the way, are rather startling entities. Growing up in South Florida, I remember seeing them from time to time:

A Rising Man won the 2017 Historical Dagger Award, and was a finalist for the Gold Dagger, the Barry for Best First Mystery, the Edgar for Best Mystery, and the Macavity Award for Best Historical Mystery.

A Necessary Evil was a Gold Dagger finalist ,as well as a finalist for the Historical Dagger and for the Barry Award for Best Mystery. The third entry in the series, Smoke and Ashes, is already out.

(This information and more is “at your fingertips” can be found at the site Stop!YoureKillingMe.com)

*************************

Then it was off to Italy, or more specifically, to Venice. Actually, the way that Donna Leon writes about La Serenissima, it seems less like a part of Italy and more like a separate principality, which, of course, it once was….

Then it was off to Italy, or more specifically, to Venice. Actually, the way that Donna Leon writes about La Serenissima, it seems less like a part of Italy and more like a separate principality, which, of course, it once was….

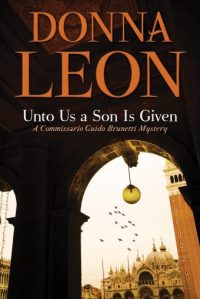

Unto Us a Son Is Given is, by my count, the 28th entry in Donna Leon’s Guido Brunetti series. Of these, I’ve read at least twenty. The Commissario and I are old friends; likewise, his wife Paola and children Raffi and Chiara. The latter has become an ardent conservationist; Brunetti is proud of her and her new found commitment to the cause.

The Brunetti family members are all getting older but at a blessedly slow rate. Reading each new book in this wonderful series gives me the chance to spend time with them in their magical dwelling place.

Brunetti’s fellow police officers are also on the scene, both those he genuinely likes, like Vianello, Signorina Elettra Zorzi, and Claudia Griffoni, and those whom he has learned to tolerate, like Lieutenant Scarpa. (That name always makes me think of Scarpia, the arch villain in Puccini’s Tosca.)

The plot – it’s not much of a mystery, really – concerns one Gonzalo Rodriguez de Tejada. This elderly gentleman is a wealthy friend of Brunetti’s father-in-law, Count Orazio Falier. Gonzalo is openly gay and, at this late stage of his life, is preparing to adopt a young man as his son. Gonzalo has no other immediate family, but he does have several siblings, including a sister to whom he is quite close. At any rate, Falier has his doubts about this prospective adoptee and asks Brunetti to see what he can discover about him.

This novel has an unusual structure for a mystery. Progress in the investigation is slow and methodical, yielding very few surprises. Then, about three quarters of the way through the book, there’s a murder. It’s sudden, and deeply shocking.

I really liked this book – well, I like every book in this series. Donna Leon is one of my favorite authors. She never disappoints – at least, that’s the case where this reader is concerned.

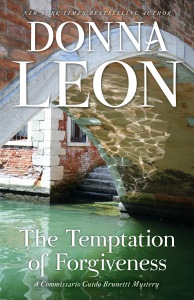

The Temptation of Forgiveness by Donna Leon

In general, I’m a big fan of Donna Leon’s mysteries. Guido Brunetti is one of the most humane and compassionate officers of the law that one could ever wish to meet, either in fiction or in real life. His family, consisting of wife and university professor (and fabulous cook) Paola and children Raffi and Chiara, now almost grown, are a pleasure to spend time with. Alas, in this latest outing, we don’t get to see much of them. This may be one of the reasons why I was less than thrilled with this particular series entry.

In general, I’m a big fan of Donna Leon’s mysteries. Guido Brunetti is one of the most humane and compassionate officers of the law that one could ever wish to meet, either in fiction or in real life. His family, consisting of wife and university professor (and fabulous cook) Paola and children Raffi and Chiara, now almost grown, are a pleasure to spend time with. Alas, in this latest outing, we don’t get to see much of them. This may be one of the reasons why I was less than thrilled with this particular series entry.

The writing is, in a crisp and unaffected way, wonderful. In this scene, Brunetti has seated himself by the hospital bed of an unconscious, badly bruised man.

He crossed his legs and studied the crucifix on the wall. Did people still think He could help them? Maybe being in the hospital refreshed their belief and made it possible again for them to think that He would. One gentleman to another, Brunetti asked the Man on the cross if He would be kind enough to help the man in the bed. He was lying there, perhaps troubled in spirit, helpless, wounded and hurt, apparently through no fault of his own. It occurred to Brunetti that much the same could be said of the Man he was asking to help; this would perhaps make Him more amenable to the request.

This scene actually surprised me, since Brunetti has, throughout this series, thought of himself as at best, an agnostic. Thus does belief sometimes steal upon us, taking us unaware, even if just momentarily.

(In The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, Sarah says, “I’ve caught belief like a disease. I’ve fallen into belief like I fell in love.”)

All this time, the victim’s wife is also in the hospital room, anxiously waiting for him to awaken. At one point, an attendant comes in and offers her a simple courtesy, which she desperately needs. Brunetti thanks the attendant for her kindness.

She was a robust women, stuffed into a uniform she seemed to be outgrowing. One loose strand of greying hair had slipped from under the transparent plastic-shower-cap thing; her hands were red and rough. She smiled. St.Augustine was wrong, Brunetti realized: it was not necessary for grace to be arrived at by prayer; it was as natural and abundant as the sunlight.

And so, what about that unconscious man? How did he get that way, and what is his fate to be? Unfortunately, this aspect of the novel was, for this reader at least, not especially compelling. The narrative dragged in places; the interviews were less than riveting. Ultimately, the solution to the mystery hinges on a fistful of discount cosmetic coupons issued by a pharmacist to an elderly lady. This transaction was analyzed at length; it was confusing and just plain dull.

Concerning Brunetti’s workplace colleagues, there are two who are portrayed in a positive light: fellow investigator Claudia Griffoni, a relatively new addition to the cast of characters; and Signorina Elettra Zorzi. Signorina Elettra, as she is usually called, is a civilian employee of the police, whose resourcefulness is legendary (as is her wardrobe).

Donna Leon has expressed her delight at the entrance of Signorina Elettra into the cast of characters in the Brunetti novels. Here’s how she puts it in an interview:

She came about one day a long time ago. I forget when she entered, the 3rd or 4th book. (the 3rd book) Really, that long ago. I was writing and someone knocked on Brunetti’s door and I didn’t have a clue who it could be or what it could be. So I went for a long walk, probably down to Sant Elena and I came back and turned on the computer and by God Signorina Elettra walked in and Thank God for the day that she did.

Not everyone is enamored of this character. One reader who most definitely isn’t is my friend Marge, whom I’ve referred to in the past as my ‘partner in crime,’ since she was the one who explained to me, when I first came to work at the library, why I should be reading mysteries. Marge is so put off by the presence – some would say the intrusive presence – of Elettra that she has stopped reading this series altogether. Ah mon Dieu! Now I’m not crazy about her either, but I don’t dislike her quite to that extent. And as I’ve indicated above, this latest is, in my view, not Donna Leon’s best work. But in a series thus far comprising twenty-seven novels, some are bound to better than others. My favorite among the more recent titles is The Waters of Eternal Youth.

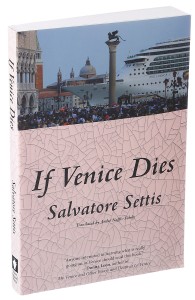

One aspect of the Brunetti novels that is a constant, and that gives great pleasure, is the setting. The city of Venice is almost a character in and of itself, unique and imperiled as it currently is. I recently read a review of a 2016 book by Salvatore Settis entitled If Venice Dies. The cover pretty well sums up the crux of the problem (click to enlarge):

Let’s hope something can be done, and in time. Meanwhile, I along with many others will continue to read the Brunetti novels and to ponder the exasperating glory of that unique city.

‘–a man as close to godhead as any mortal who had ever lived–could such a man be alive one moment…and dead the next?’ – The Throne of Caesar by Steven Saylor

The Throne of Caesar begins in this wise:

The Throne of Caesar begins in this wise:

Once upon a time, a young slave came to fetch me on a warm spring morning. That was the first time I met Tiro.

Gordianus hastens to inform us that this was a long time ago. Now, Tiro is no longer a slave. He is a freedman, having been manumitted some years ago by his master Cicero. And after the passage of many years and the experience of numerous adventures, Gordianus, called Finder, is quite a bit older and, he hopes, wiser. His family is flourishing. The omens are propitious. And he himself is about to be receive an unexpected and significant honor, bestowed by none other than the great Julius Caesar, with whom he has become a favorite.

What could possibly go wrong? Here’s a clue: the novel opens with a page upon which only the date is divulged. That date is March 10.

That’s right; six days before one of the most famous dates in the history of the Western World: March 15, the Ides of March.

So: do we readers just wait in dread of the inevitable? Well, that element of suspense is certainly present from the start, but much else is going on as well. Gordianus’s son Meto has become indispensable to Caesar as his secretary and general right hand man. Daughter Diana and her husband, the hulking bodyguard Davus, live with Gordianus and his wife, the beautiful and imperious Bethesda. (One imagines that no one has ever done “imperious” quite the way the Roman matrons did.) Cinna the poet is a favorite drinking buddy of Gordianus’s. The great orator Cicero, somewhat past his prime, is nervously on the scene. And then there’s the haruspex Spurinna….

A haruspex was a soothsayer who specialized in the reading of entrails. This skill was closely identified with the religion of the Etruscans.

Spurinna was supposedly the name of the soothsayer who has warned Caesar to “Beware the Ides of March.” One of the most chilling moments in Shakespeare’s play occurs when, on his way to the Senate, Caesar encounters Spurinna for the second time. Feeling rather full of himself, Caesar observes that “The Ides of March are come.” To which the soothsayer responds, without missing a beat, “Ay, Caesar, but not gone.”

And yet, in the days before the Ides, life goes on, filled with plots, counter- plots, and various intrigues, and gossip, just as the Romans loved it. Also, at the time, poetry played a big part in the cultural life of the people. Cinna’s latest opus, entitled Zmyrna, was incessantly read and talked about. (The author’s full name is Helvius Cinna, not to be confused with Lucius Cornelius Cinna, praetor and conspirator. Alas, despite the protestations of Helvius Cinna, that confusion does in fact occur, with disastrous results for the poet. You’ll recall Shakespeare’s memorable line: “Tear him for his bad verses, tear him for his bad verses.”)

At any rate, back to Zmyrna: Impatient with his father’s delay in reading this putative masterpiece, Meto begins reading aloud to him. Here’s how Gordianus responds:

I thought I would prefer those moments when Meto read aloud, for he had a beautiful voice and knew exactly where to place each stress depending on the secret meanings of the words. But I enjoyed just as much the experience of reading the verses aloud myself, letting my lips and tongue play upon the absurdly convoluted edifice of language. Even when I didn’t quite understand what I was reading, the words themselves produced music. When I did understand not merely the outermost level of meaning but also the multiple puns and learned references, I felt an added thrill, as if the words that emerged from my mouth were truly something more than air, compounded of some enchanted substance that encircled and gently caressed both Meto and myself.

Beautiful description that, and how eloquently it limns the closeness and mutual affection of father and son. (When I went in search of the actual Zmyrna, I was informed succinctly by Wikipedia that “The poem has not survived.”)

Oh and speaking of ‘learned references,’ Caesar, during a later literary-themed conversation, comes up with this idea:

“Imagine a series of life stories told in parallel, to compare and contrast the careers and fortunes of great men.”

Of course, Plutarch not only imagined this, he wrote it, some hundred and fifty years after Caesar’s fanciful speculation, as rendered by Steven Saylor.

Here’s another set piece that I love. This is actually the same occasion at which Caesar made the comment above:

To either side of me, braziers burned. Torches flickered from various sconces in the surrounding portico. The last faint light of day lit the ashen sky, in which the first stars had begun to shine. The four men moved amid green shrubs and tall statues. The ever-changing light, the men in their finery, the looming figures of marble, and bronze–all combined in a moment of surpassing strangeness. I looked at Meto, wondering if he, too, felt it. On his face I saw a look of deep contentment that increased with each step that brought Caesar nearer.

Scenes like this, with their portentous quietude, serve to make the intimations of coming bloodshed feel all the more harrowing.

Steven Saylor obviously derives a deep joy from a lifelong immersion in the life and literature of ancient Rome. He passes that joy directly on to us, the readers of his Roma Sub Rosa series. His erudition is everywhere evident, but it never hijacks the narratives, which are invariably compelling, set as they are against a background of actual events from ancient times. Those times spring vividly to life in his stories of ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events. It cannot be an easy task to conjure a world whose inhabitants had such a drastically different world view than our own. (It’s hard, for instance, to accept the fact that educated, cultured individuals gave credence to the reading of animal entrails.) And yet this author accomplishes this feat, with conviction and brio.

The art work that graces the cover of The Throne of Caesar is by Karl Theodor Piloty and was painted in 1865.

I also like this version of the event, painted by Jean-Leon Jerome in 1867.

On Steven Saylor’s richly informative site, I note with delight a celebration of the 25th anniversary of the publication of Roman Blood. How well I remember reading it when it came out in 1991 and thinking, Wow, what a winner this is!

I ask only this of any work of historical fiction that I read: Put me there, in that place, at that time. This is, after all, the only form of time travel we have, so make it work. In his marvelous series of novels treating of the life and times of Gordianus the Finder, proud and resourceful citizen of ancient Rome, Steven Saylor (whom we had the pleasure of meeting at Crimefest in 2011) does exactly that.

Gleanings from Vasari’s LIVES and THE COLLECTOR OF LIVES, by Rowland and Charney

This is the second and final post on Vasari’s Vite (Lives) and the biography Collector of Lives.

As Michelangelo was preparing to unveil his monumental sculpture of David, Piero Soderini, who occupied the high post of Gonfoloniere of Justice in the government of Florence, arrived on the scene. As he gazed upon the great artist’s masterwork, he voiced the opinion that David’s nose was too thick. Whereupon Michelangelo proceeded – or appeared to proceed – to remedy this imperfection. Vasari describes what happened next:

Michelangelo, realizing that the Gonfaloniere was standing under the giant and that his viewpoint did not allow him to see it properly, climbed up the scaffolding to satisfy Soderini (who was behind him nearby), and having quickly grabbed his chisel in his left hand along with a little marble dust that he found on the planks in the scaffolding, Michelangelo began to tap lightly with the chisel, allowing the dust to fall little by little without retouching the nose from the way it was. Then, looking down at the Gonfaloniere who stood there watching, he ordered:

‘Look at it now.’

‘I like it better,’ replied the Gonfaloniere: ‘you’ve made it come alive.’

Vasari knew many of the artists that he wrote about it; he also knew that people loved hearing inside jokes and gossip about those same artists. His Lives is thus filled with such anecdotal material. Some of it may be apocryphal; but such stories enliven his text and are a major aspect of what makes it still so readable and entertaining.

“Vasari’s stories tend to endure, even when scholarship overturns them.” Rowland and Charney in The Collector of Lives

In 1506, during the excavation of a vineyard in Rome, workers broke through to the remains of the Golden House (Domus Aureus). This was an elaborate palace-cum-park created by Nero, built from 64 to 68 AD following the destruction wrought by the Great Fire of 64 AD. Workers soon found themselves uncovering an extraordinary sculpture: the Laocoon Group.

Not only was this work astonishing in and of itself, but it exercised a profound influence on Michelangelo, who happened to be in Rome when it was first brought out of the earth and back into to the light of day. (When the work of excavation was complete, the Laocoon Group was brought to the Vatican, where it still is, and where I saw it several decades ago.)

Here are Rowland and Charney on the subject of the Laocoon:

The statue is astonishing for its realism, the hyper-accurate musculature of Laocoon and the adolescent bodies of his sons as they struggle against the tightening coils of the serpents, one of which is about to bite Laocoon’s flank. It is a frozen moment of highest tension. Muscles are taut, the serpent’s jaw is set to clamp down, an expression of adrenaline-pumped effort,, pain, and hopelessness can be read in the face of Laocoon.

The authors go on to point out that this is an extremely different effect than that which Renaissance sculptors normally strove to convey in their work.

During the High Renaissance, when so many great artists were at work in northern Italy and in Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, painters established workshops where apprentices ground pigments, prepared canvases, and performed other tasks. If an apprentice showed promise, he could learn technique from the master. In fact, many masters emerged from this system, Vasari himself among them.

There’s an interesting post on this subject at the Art Post Blog.

Rowland and Charney have a vivid description of what it must have been like to work in such a place:

In a Florentine painter’s studio…scents of linseed oil, sweat, and sawdust would have greeted the visitor outside the door. Ideally, the large windows would face south to catch the best possible light, and the studio had to be tall enough, and wide enough, to accommodate altarpieces of all sized. Sawdust, scattered on the floor, absorbed splatters and facilitated cleaning as apprentices. like Vasari, aged eight to eighteen, mingled with older paid assistants, bustling around the space, sweating profusely into grimy leather smocks, laughing, cursing, mopping, grinding pigments, creating an atmosphere that was surprisingly lively and social.

They add that the image many of us carry in our minds of the lone artist struggling to achieve his goal simply did not apply here. For example, Lucas Cranach (1472-1553) of Wittenberg ran “a veritable factory.”

(I can never hear of Wittenberg without thinking of Hamlet: “Go not to Wittenberg,” the Queen implores her son, thereby sealing her fate, his, and that of many others at the ill-fated Danish court.)

This paragraph on Leonardo da Vinci pretty well sums up the man’s astonishing achievements:

Leonardo’s legacy in art was far greater than his modest output would suggest. The development of techniques like sfumato (the intentional blurring of color to create a smoky, atmospheric effect), chiaroscuro (the dramatic focus on emerging from darkness), and replicating nature with as much accuracy as possible (such as employing “atmospheric perspective,” in which objects far in the distance appear hazier, as we view them through layers of atmosphere, and pinpoint accurate anatomy as studied from dissections) all made a lasting impression and influenced future generations of artists. His books (on art, and on mathematics) helped to disseminate his ideas. His inventions, more of them designed than actually built, showed tremendous forethought: he was the first to conceive of helicopters, machine guns, tanks, parachutes, foldable bridges, and more.

(And still with me is the moment last December when my sister-in-law Donna and I stood before Leonardo’s other worldly masterpiece The Virgin of the Rocks, in London’s National Gallery.)

Vasari did not want to elevate any artist to the level of his revered and beloved Michelangelo; nevertheless, he readily acknowledged the supreme gifts of Raphael:

His colours were finer than those found in nature, and his invention was original and unforced, as anyone can realize by looking at his scenes, which have the narrative flow of a written story. They bring before our eyes sites and buildings, the ways and customs of our own or of foreign peoples, just as Raphael wished to show them. In addition to the graceful qualities of the heads shown in his paintings, whether old or young, men or women, his figures expressed perfectly the character of those they represented, the modest or the bold being shown just as they are. The children in his pictures were depicted now with mischief in their eyes, now in playful attitudes. And his draperies are neither too simple nor too involved but appear wholly realistic.

Raphael’s Alba Madonna has long been one of my favorite works of art in Washington’s National Gallery. Painted circa 1510

Vasari brought home to me the importance of Masaccio in the evolution of Italian painting. I hadn’t realized how key his contribution was:

The superb Masaccio completely freed himself of Giotto’s style and adopted a new manner for his heads, his draperies, buildings, and nudes, his colours and foreshortenings. He thus brought into existence the modern style which, beginning during his period, has been employed by all our artists until the present day, enriched and embellished from time to time by new inventions, adornments, and grace.

Masaccio’s achievement and influence are all the more astonishing when the brevity of his life is taken into account: he died at the age of 26. Vasari appends a rather provocative speculation to his remarks on this artist:

Although Masaccio’s works have always had a high reputation, there are those who believe, or rather there are many who insist, that he would have produced even more impressive results if his life had not ended prematurely when he was twenty-six. However, because of the envy of fortune, or because good things rarely last for long, he was cut off in the flower of his youth, his death being so sudden that there were some who even suspected that he had been poisoned.

Vasari does not elaborate on this startling conjecture; rather, he goes on to note that upon hearing the news, the great painter and architect Filippo Brunelleschi was grief stricken and exclaimed: “‘We have suffered a terrible loss in the death of Masaccio.’”

Rowland and Charney assert that had Vasari not made note of several women artists, we might not know about them. They refer specifically to Sofonisba Anguissola and her sisters – she had six of them! – and Properzia de’ Rossi of Bologna. Vasari had actually had occasion to meet Sofonisba and three of her sisters when he was visiting Cremona, where their family belonged to the local aristocracy. He was deeply impressed by a particular work of Sofonisba’s:

This year in Cremona I saw in her father’s house a painting by her hand made with great diligence showing her three sisters playing chess, and with them an old housemaid, with such diligence and attention that they truly seem to be alive and missing nothing but the power of speech.

As for Properzia de’ Rossi, she was famous primarily for her carvings on nuts and on fruit pits. I read somewhere that this meticulous endeavor was deemd especially well suited for a woman to undertake, as it required both patience and diligence.

Giorgio Vasari and Michelangelo Buonarroti

I feel as though The Collector of Lives were written just for me. Admittedly, it is a rather specialized narrative, concentrating as it does on the work of the great Giorgio Vasari and the Italian painters of the Renaissance whom he celebrates in his magnum opus, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. (‘Excellent’ is sometimes rendered as ‘Eminent.’)

I feel as though The Collector of Lives were written just for me. Admittedly, it is a rather specialized narrative, concentrating as it does on the work of the great Giorgio Vasari and the Italian painters of the Renaissance whom he celebrates in his magnum opus, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. (‘Excellent’ is sometimes rendered as ‘Eminent.’)

Amazingly, there were those who practiced more than one of these arts – in some cases, with a varying degree of proficiency, all three. Vasari himself was proficient both as a painter and an architect; it was he who designed the Uffizi, now Florence’s preeminent art museum. Add to which, of course, he was an extremely skilled writer. By means of this one book, he legitimized art history as a field of study. He was helped in this endeavor by he fact that he knew personally a good number of the artists whose lives and works he describes in such a lively and engaging manner.

(Vasari’s book is sometimes referred to simply as The Lives. You will see it occasionally called in Italian Vite – pronounced ‘veetay.’)

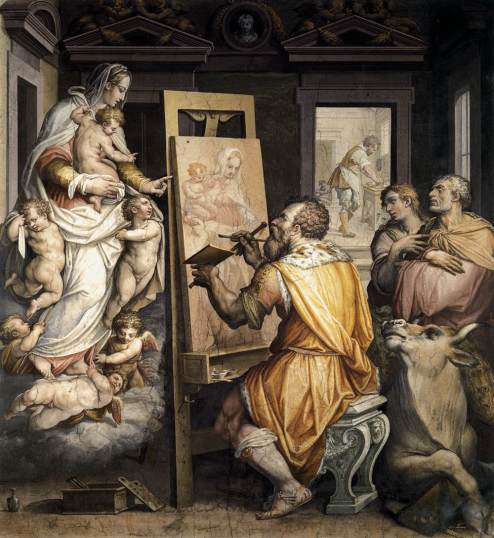

The cover of The Collector of Lives features a detail from St. Luke Painting the Virgin by Vasari; it dates from about 1565. My copy of Vasari’s book has the same work on its cover:  Here is the actual painting:

Here is the actual painting:

I often see comments to the effect that while Vasari achieved greatness through his writing, he was not quite great as a painter. I find this airy dismissal rather unwarranted. True, in his era he was up against some incredibly gifted artists; nevertheless, I find his own work singularly compelling.

Vasari’s own hero in the arts was unquestionably Michelangelo. Many of us are familiar with Michelangelo’s most famous creations, but I think, especially in this age of anguish in which we now seem to dwell, it might do us good to look at them again:

The Sistine Chapel

It would be impossible for any craftsman or sculptor no matter how brilliant ever to surpass the grace or design of this work or try to cut and polish the marble with the skill that Michelangelo displayed. For the Pietà was a revelation of all the potentialities and force of the art of sculpture. Among the many beautiful features (including the inspired draperies) this is notably demonstrated by the body of Christ itself. It would be impossible to find a body showing greater mastery of art and possessing more beautiful members, or a nude with more detail in the muscles, veins, and nerves stretched over their framework of bones, or a more deathly corpse. The lovely expression of the head, the harmony in the joints and attachments of the arms, legs, and trunk, and the fine tracery of pulses and veins are all so wonderful that it staggers belief that the hand of an artist could have executed this inspired and admirable work so perfectly and in so short a time. It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists

The legs are skilfully outlined, the slender flanks are beautifully shaped and the limbs are joined faultlessly to the trunk. The grace of this figure and the serenity of its pose have never been surpassed, nor have the feet, the hands, and the head, whose harmonious proportions and loveliness are in keeping with the rest. To be sure, anyone who has seen Michelangelo’s David has no need to see anything else by any other sculptor, living or dead.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists

I only found out recently that Michelangelo was also a poet:

“When the Author Was Painting the Vault of the Sistine Chapel” (1509)

I’ve already grown a goiter from this torture,

hunched up here like a cat in Lombardy

(or anywhere else where the stagnant water’s poison).

My stomach’s squashed under my chin, my beard’s

pointing at heaven, my brain’s crushed in a casket,

my breast twists like a harpy’s. My brush,

above me all the time, dribbles paint

so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!My haunches are grinding into my guts,

my poor ass strains to work as a counterweight,

every gesture I make is blind and aimless.

My skin hangs loose below me, my spine’s

all knotted from folding over itself.

I’m bent taut as a Syrian bow.Because I’m stuck like this, my thoughts

are crazy, perfidious tripe:

anyone shoots badly through a crooked blowpipe.My painting is dead.

Defend it for me, Giovanni, protect my honor.

I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.

Just in case you thought painting that ceiling was in any way an easy undertaking….

Michelangelo also wrote poems of a more lyrical nature, such as this one in praise of the author of The Divine Comedy:

DANTE

What should be said of him cannot be said;

By too great splendor is his name attended;

To blame is easier than those who him offended,

Than reach the faintest glory round him shed.

This man descended to the doomed and dead

For our instruction; then to God ascended;

Heaven opened wide to him its portals splendid,

Who from his country’s, closed against him, fled.

Ungrateful land! To its own prejudice

Nurse of his fortunes; and this showeth well

That the most perfect most of grief shall see.

Among a thousand proofs let one suffice,

That as his exile hath no parallel,

Ne’er walked the earth a greater man than he.

Translated into English by H.W. Longfellow (1807-1882).

More poetry by Michelangelo can be found at the Michelangelo Gallery.

In The Collector of Lives, Ingrid Rowland and Noah Charney offer this assessment:

There are many bones one can pick with Vasari, but he makes a persuasive argument for his candidate as the “greatest” artist in history. To this day, Michelangelo Buonarroti seems a reasonable choice as Giorgio’s ultimate hero.

There are many other genius artists of the Italian Renaissance whom Vasari admired and wrote about. I’ll return to these in a later post.

A hundred years after Michelangelo, Gregorio Allegri composed the Miserere Mei, Deus expressly to be sung in the Sistine Chapel during Holy Week. Here, it is performed by the King’s College Choir in their magnificent Chapel.

British art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon has made a two part film about Giorgio Vasari:

‘Somewhere deep in the soul of the instrument was the indelible memory of that one great man.’ – Paganini’s Ghost, by Paul Adam

This is a great mystery for lovers of both classical music and Italy. Gianni Castiglione is a luthier – a maker of violins and other stringed instruments. He lives and works in Cremona, a city that has long been the center for this exacting art. Previous practitioners include Antonio Stradivari, Andrea Guarneri, and Andrea Amati. Instruments crafted by these past masters still command steep prices. In the ways that count, though, they are priceless.

This is a great mystery for lovers of both classical music and Italy. Gianni Castiglione is a luthier – a maker of violins and other stringed instruments. He lives and works in Cremona, a city that has long been the center for this exacting art. Previous practitioners include Antonio Stradivari, Andrea Guarneri, and Andrea Amati. Instruments crafted by these past masters still command steep prices. In the ways that count, though, they are priceless.

Luthiers also condition and repair existing instruments, and it is in this capacity that Gianni has been sought out by Yevgeny Ivanov, a youthful violinist whose career is just taking off, and his imperious and overbearing mother, Ludmilla. The mystery begins with this seemingly straightforward encounter and gains in complexity until, I admit, I was having some trouble keeping track of the cast of characters and the twists and turns of the plot. But as is so often the case with this kind of crime fiction, it didn’t bother me. I was so thoroughly engaged with the lore of the violin and its fascinating history, especially as it relates to that brilliant and tempestuous legend, Niccolo Paganini. Also helpful is the fact that Paul Adam’s prose is exceptionally fine. In this scene, Gianni is working on a violin that was once Paganini’s. He’s working under time constraints and has to get it right:

I was conscious of the time ticking by as I worked on the violin, but I tried not to let it disturb me. I also tried not to think of the status of the instrument. I had to regard it as an ordinary violin, not the violin that had belonged to the most celebrated virtuoso in history. But it wasn’t easy. Every time I touched it, I was aware that Paganini’s hands had been there before mine. His fingers had held it; his chin had rested on the front plate; his breath had drifted over the varnish. Somewhere deep in the soul off the instrument was the indelible memory of that one great man.

Handling the violin gave me a strange feeling of transience. It had been made two centuries before I was born and it would survive long after I was gone. It wasn’t passing through my life; I was passing through its life, just as Paganini had passed through it.

Paul Adam studied law at Nottingham University before embarking on a career in journalism. He is the author of twelve novels for adults, including the two that currently comprise the Cremona series. He has also written the Max Cassidy Trilogy for young readers.

In the above bio, I could find no indication of where or when Adam’s deep love for, and knowledge of, the violin had come into his life. Fortunately, I found an interview in which he explained that he’d played the violin as a child and long been interested in its history and in the city of Cremona.

I finished this novel several weeks ago, but it’s been brought vividly to mind by an extremely poignant essay I just read in The New Yorker. Entitled “A Tech Pioneer’s Final, Unexpected Act,” it is also about a young violinist and the power of music to exalt and to heal.