Reeling from sheer delight at the National Gallery

Some friends and I wanted to see the Degas / Cassatt exhibit. This was enjoyable, if less than spectacular. Of course, one loves the little girl in the blue chair, the perfect picture of youthful ennu:

(This work puts me in mind of the painting of Agatha Christie as a young girl that hangs in Greenway, the writer’s country home on the Devon coast.

The colors are different; the body language and facial expressions, similar.)

The colors are different; the body language and facial expressions, similar.)

I especially loved Degas’s Rehearsal in the Studio. There’s something about the way the light flows into the room….

After viewing the exhibit, we each went our separate ways. I decided to seek out some of my favorites from among the works in the National Gallery’s permanent collection. It had been too long since I’d seen them.

********************************************

I actually saw Manet’s The Old Musician while on my way to Degas / Cassatt. It stopped me in my tracks.

I’m not sure why this painting affects me as it does. I am held by the musician’s unwavering gaze. I feel a powerful urge to enter right into the scene. In my mind, I do just that.

******************************************

Everything I love about “England’s green and pleasant land” is embodied here in John Constable’s Wivenhoe Park, Essex. (Be sure to click to enlarge.)

********************************************

The Danae, by Titian. We’re lucky to have this masterpiece. It was looted by the Nazis and recovered by the famous Monuments Men from inside a salt mine in Austria.

*********************************************************

*******************************************

‘Whenas in silks my Julia goes

Then, then (methinks) how sweetly flows

That liquefaction of her clothes.’

*****************************************************

La Camargo dancing , by Nicolas Lancret

*****************************************

****************************************

********************************************

***********************************************

***************************************

I was not familiar with this moving work by Murillo, but it summoned up pictures I’ve seen of the same subject as portrayed by Rembrandt. (This painting is in Russia’s Hermitage Museum.):

It’s interesting, the power that this New Testament parable holds over the artistic imagination. (It appears only in the gospel of Saint Luke.) The Murillo canvas is certainly beautiful (and I confess that I especially appreciate the sweet presence of the small dog), but Rembrandt’s rendering is something quite apart and almost unbearably poignant.

The Parable of the Prodigal Son is my husband’s favorite passage from the Bible. Ron is especially partial to the ballet, with music by Sergei Prokofiev and choreography by the great George Balanchine. This video is of a 1978 performance by the New York City Ballet, with the incomparable Mikhail Barishnikov as the Prodigal. The last few minutes are just – well, I lack the words to describe that scene. You’ll have to see for yourself:

Some great reading this summer

The fact is, I’ve fallen hopelessly behind in reviewing my recent reads. This does not mean that they’ve been disappointing. On the contrary, they’ve been exceptionally good – in a couple of cases, even great. And virtually all of them merit serious consideration by book discussion groups. (In cases where I’ve previously written about a work, I’ve provided links.)

MYSTERY

AFTER I’M GONE by Laura Lippman

Yet another gem from Lippman, a beloved local institution. Here she talks about her latest novel at Washington’s Politics and Prose, another beloved local institution. I found very interesting her insistence on the distinction between a plot that’s ‘inspired by,’ as opposed to ‘based on,’ actual events and/or persons.

THE RESISTANCE MAN by Martin Walker.

My only problem with this latest entry in the Bruno Chief of Police series is that the complexity of the plot tended to interfere with the immersion in the food and wine of France’s fabulous Dordogne region. And I simply could not get enough of Bruno’s endlessly tangled love life and the antics of his new basset hound puppy Balzac. (Said canine serves to remind Bruno that he really must get back to reading the classics, a timely reminder for this reader as well.)

BLACK LIES, RED BLOOD – Kjell Eriksson

NO MAN’S NIGHTINGALE – Ruth Rendell

I confess to possessing no objectivity concerning the works of Baroness Rendell of Babergh. She could write advertising copy (as Dorothy L Sayers did so entertainingly) and I would no doubt be enthralled. I’m partial to the Wexford procedurals, but really, anything will do. Her latest, The Girl Next Door, is due out next month.

FICTION

THE INVENTION OF WINGS – Sue Monk Kidd

I would not have read this book had it not been a selection of the AAUW Readers. It’s turned out to be the classic case of reluctance turned into enthusiasm.

I’d tried to read Kidd’s first novel, The Secret Life of Bees, and I hadn’t cared for it. I thought the author was trying too hard to create a mystical aura; in addition, the characters seemed stereotypical. In my view, that is not true of The Invention of Wings. For one thing, the novel is based on the actual lives of the Sarah and Angelina Grimké, two sister from South Carolina who traveled north to become Quakers and fervent abolitionists in the early years of the nineteenth century. Their story is compelling, but even more compelling is the story of their slaves. Kidd relates their ghastly lot, and the suffering of their fellows in bondage, without pulling any punches. It is a story that is both enraging and excruciating.

There are a few instances of awkward writing in this novel, but not enough to spoil the reading experience. Altogether, I’d say it’s a triumph of historical fiction and a timely reminder – for such reminders are always needed – of the specific horrors suffered by innocent people at the hands of those who “owned” them, who professed themselves good Christians, and who were happy to delude themselves and their fellows with false bromides and senseless justifications concerning their “peculiar institution.”

THE CHILDREN ACT – Ian McEwan

I read no reviews. My anticipation was great. I wanted this consummately gifted writer to astonish me once again.

And he did.

In a recent New Yorker review of The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell, James Wood makes the claim that in our time, the novel has lost its cultural relevance and in consequence has forsaken the search for meaning, aiming instead to deliver nothing deeper than an engrossing tale:

Meaning is a bit of a bore, but storytelling is alive. The novel form can be difficult, cumbrously serious; storytelling is all pleasure, fantastical in its fertility, its ceaseless inventiveness. Easy to consume, too, because it excites hunger while simultaneously satisfying it: we continuously want more. The novel now aspires to the regality of the boxed DVD set: the throne is a game of them. And the purer the storytelling the better—where purity is the embrace of sheer occurrence, unburdened by deeper meaning. Publishers, readers, booksellers, even critics, acclaim the novel that one can deliciously sink into, forget oneself in, the novel that returns us to the innocence of childhood or the dream of the cartoon, the novel of a thousand confections and no unwanted significance. What becomes harder to find, and lonelier to defend, is the idea of the novel as—in Ford Madox Ford’s words—a “medium of profoundly serious investigation into the human case.”

Soon after reading this piece by Woods, I was riveted by a passage filled with almost unbearable tension in The Children Act. The stakes could not have been higher nor the dilemma more profound, and the resolution depended on the judgment of a single individual.

At that moment, I could think of no more powerful refutation of Woods’s contention. In the masterful hands of Ian McEwan, meaning could not be less of a bore. It is, in fact, everything.

SPARTA – Roxana Robinson

Yet another book I probably wouldn’t have read had it not been a book club ‘assignment.’ This story of a young Iraq war veteran’s difficult return to civilian life is both poignant and hard hitting. Robinson’s writing is exquisite.

AN OFFICER AND A SPY – Thomas Harris

THE WEIGHT OF WATER – Anita Shreve

Somehow I’d never gotten around to reading anything by Shreve, an extremely well liked author among readers of contemporary fiction. I chose The Weight of Water because the plot involves the revisiting of an appalling double murder that took place in 1873 on the Isles of Shoals, a group of islands off the coast of New Hampshire and Maine. The crime is usually referred to by the name Smuttynose, the name of the actual island on which the murders occurred.

I’d never heard of the killings on Smuttynose – never heard of the Isles of Shoals, for that matter – before encountering the story in Harold Schechter’s true crime anthology. Having read almost all of the selections in that book, I have to say that this is the crime that I have found most haunting. This is no doubt due in part to Celia Thaxter’s powerful retelling of events. Her piece is entitled “A Memorable Murder;” it was first published in 1875 in the Atlantic Monthly, as the magazine was then called. I’d never before heard of Celia Thaxter. She turns out to have been an exceptional person, one well worth knowing about.She was a native of the Isles of Shoals, and was living on Appledore, one of the other islands, when the crime took place on Smuttynose.

Celia Thaxter’s Garden by Childe Hassam, 1890

Past and present kept colliding with each other in The Weight of Water. The material was well handled; I very much enjoyed the novel.

STONER – John Williams

Last June, my friend Cristina returned from several weeks touring Europe with the news: “Everyone’s reading Stoner over there!”

Published in 1965 and achieving at the time only middling success, Stoner has been revived to great acclaimed, championed by the likes of Ian McEwan and Julian Barnes.

William Stoner is a college professor of modest means and even more modest aspirations. In some ways fate is cruel to him, but perhaps not more than it is to any man or woman striving for a modicum of happiness and success in this life. Stoner reminds me in some ways of The Wife of Martin Guerre: in both novels, the narrative commences with great restraint, only to become increasingly powerful as the story progresses. In both books, the ending comes close to being shattering.

I remember being at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s celebrated American Wing several years ago and feeling distinctly intrigued by this painting:

The subject seemed to be worn down by some unnamed burden of sorrow. As it turns out, Mr. Kenton himself is something of an enigma. I thought it an apt choice for the cover of the reissue of Stoner from New York Review Books.

John Williams’s novel is intensely moving; at times, almost devastating. The writing is marvelous.

Like Stoner, this is the story of a man’s life, from youth to old age. Harry Sanders works for the U.S. Foreign Service. As the novel opens, he’s a young attache in Southeast Asia – probably Vietnam, though Just does not specify. While on duty there, he meets a German aid worker based on a nearby hospital ship. Harry and Sieglinde fall passionately in love. Then chance and circumstance separate them.

The remainder of Harry’s work life and his ever evolving personal life both makes for an absorbing story, but as so often happens, the intense drama of his first assignment and his first love affair is never quite duplicated.

Ward Just is a veteran fiction writer and newspaper reporter. His accomplishments in both fields have been recognized. (He was the Washington Post’s Vietnam correspondent.) This high praise for American Romantic from Kirkus Reviews is entirely justified (no pun intended, but hey, why not?).

At lunch this past Monday, my friend Angie was praising the opening chapter of The Children Act. I agree with her that it sets the tone beautifully for what comes next. But I think the so-called Prelude to the first chapter of American Romantic is even more striking. Traveling by boat, Harry Sanders penetrates deep into the jungle. His purpose is to inspect some projects that have been initiated in certain villages. He’s particularly interested in a clinic established in one of them. But when he gets there, he’s greeted by a sight that poignant, tragic, and terrible all at once. It’s an amazing scene, perfectly rendered.

NONFICTION

A SPY AMONG FRIENDS: KIM PHILBY AND THE GREAT BETRAYAL – Ben Macintyre

THE FAMILY ROMANOV: MURDER, REBELLION, AND THE FALL OF IMPERIAL RUSSIA – Candace Fleming

THE GOOD NURSE – Charles Graeber

THE GOOD NURSE – Charles Graeber

The book’s full title is The Good Nurse: A True Story of Medicine, Madness, and Murder. Once again, I was reading for a discussion group, the Usual Suspects this time. I confess I was somewhat dismayed by the first few pages, as the writing struck me as awkward, even clumsy. But it doesn’t take Charles Graeber long to hit his stride, and once he does… Let’s put it this way: I did nothing for three days but read The Good Nurse, all the while exclaiming over and over again, Oh no, not again, oh my God…. Nurse Charlie Cullen began committing his depredations in the 1980’s while employed at St. Barnabas Hospital in Livingston, New Jersey. My father was almost certainly a patient there at that time, so this tale gained an extra creepy dimension for me as a result.

The Good Nurse is a different kind of true crime book. Cullen’s crimes were accomplished through stealth and trickery. Many times the authorities and medical experts had trouble determining whether a crime had actually been committed. Cullen’s callous abuse of his position of trust in life-or-death situations makes for horrific reading. I admire Charles Graeber for being able to penetrate the thicket of this medical mystery and by doing so, exposing it to the light of day. A number of hospitals and health care facilities do not come off well in Graeber’s telling. But in fairness there are some heroes in this narrative as well. If they hadn’t pushed for the truth, Cullen’s crime spree might have lasted even longer than the sixteen years that it did go on.

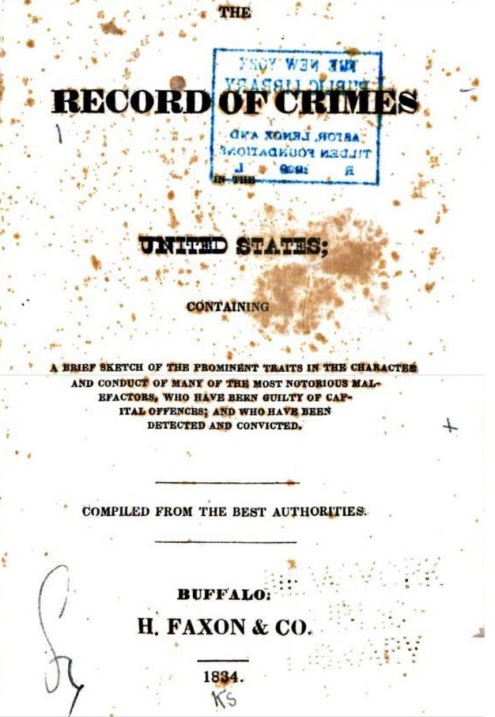

TRUE CRIME: AN AMERICAN ANTHOLOGY – Harold Schechter, editor

I’ve already written about this terrific anthology; there will be more to come, as I continue preparing for the True Crime course I’ll be teaching next February and March.

Now We Are One!!

Happy Birthday, Darling Welles!!

The Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion, and the Fall of Imperial Russia by Candace Fleming

A photograph that haunts, taken in 1913.

The Romanov dynasty requires a male heir. Alas for the Tsarina Alexandra, one pregnancy after another produces daughters. She becomes worn out with the effort. Then on the fifth try- triumph! Alexei Nikolaevich is born on August 12, 1904. Finally, the birth of a male heir insures an orderly succession.

But it was not to be.

Through his mother, Alexei had inherited a terrible affliction. Hemophilia is a disorder of the blood in which little or no clotting factor is present. Wounds take longer to heal, and worse, victims suffer internal bleeding that is difficult to stanch and liable to harm internal organs, tissues, and joints. In Alexei’s case, bleeding into his knee joints caused him excruciating pain and made him, from time to time, unable to walk.

While his parents obsessed over his health they kept up appearances, so that the outside world in general and their subjects in particular would never doubt their divine right to absolute sovereignty over the people of Russia. Yet they were curiously blind to the turbulence, anger, and desperation that were rife among those same people.

How the Romanovs could be so oblivious to what was going on right in front of them is certainly a mystery. What is not a a mystery – at least, not any longer – is the terrible price paid by the entire family for this willed ignorance.

The Family Romanov is being reviewed as a book for young readers. I’d be delighted if middle school or high school students became acquainted with this fascinating and chilling episode of history. The story of the Romanovs is full of passion, romance, and tragedy. Above all, as you read this book, you sense the hand of fate hovering over this family, almost from the beginning of Nicholas’s disastrous reign.

One thing that Candace Fleming does that I found very effective was to show, by means of photographs and various writings from the era, the stark contrast between the privileged existence of the Russian aristocracy and the terrible grinding poverty in which the masses were forced to live. This is a complex story but I was in thrall to its relentless trajectory. The end is inevitable, almost preordained. I’ve read this story many times, and I’m stunned every time by the pity and the horror of it.

*******************************************

*******************************************

The Romanovs and their world are well represented on YouTube. Here is some footage from British Pathé. It is silent yet it speaks volumes:

******************************************

I had The Family Romanov out from the library, but because of its terrific bibliography I decided to download the e-book. Fleming cites a number of primary sources of which I’d not previously been aware.

Here is a sampling:

Alexander, Grand Duke of Russia. Once a Grand Duke. Garden City, NY: Garden City, 1932.

Alexandra, Empress of Russia. The Letters of the Tsaritsa to the Tsar, 1914–16. London: Duckworth, 1923.

Botkin, Gleb. The Real Romanovs. New York: Revell, 1931.

Buchanan, Meriel. The Dissolution of an Empire. London: John Murray, 1932.

Buchanan, Sir George. My Mission to Russia and Other Diplomatic Memories. 2 volumes. Boston: Little, Brown, 1923. Bulygin, Paul, and Alexander Kerensky. The Murder of the Romanovs. London: Hutchinson, 1935.

********************************************************

In his book Stone Voices: The Search for Scotland, Neal Ascherson says of Russia that it’s a place “…where the past is said to be unpredictable.” Here is the first segment of a 1994 National Geographic special called The Last Tsar. It opens with a description of the post-Soviet reemergence- indeed one might almost say, resurrection – of Tsar Nicholas II:

Over a period of years, starting in the 19970s, bones belonging to the bodies of royal family members were uncovered, removed from the earth, and positively identified. Finally, in 1998, the Romanovs and several others who’d been executed along with them were buried with all due solemnity in the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, in Saint Petersburg. Present at the interment were numerous dignitaries as well as living decendants of the House of Romanov.

****************************************************

Russia’s history is a turbulent mixture of cruelty, catastrophe, and exaltation. It can exert a powerful pull on those who have fled from it. Sergei Rachmaninoff experienced great success as a musician and composer during his life in America and Western Europe. Yet he never stopped feeling like an exile. It is why Tony Palmers’ wonderful film biography of him is entitled The Harvest of Sorrow: