‘This was machair, that quintessentially Hebridean landscape–part beach, part sand dune, part field of tiny flowers.’ – The Geometry of Holding Hands, by Alexander McCall Smith

For the past two weeks, I’ve been happily marinating in the works of Alexander McCall Smith. To begin with, I just finished The Geometry of Holding Hands, the latest entry in the Isabel Dalhousie series. Isabel and her beloved Jamie are happily married and now the parents of two little boys, Charlie and Magnus. The dependable presence of Grace, housekeeper and now also child minder, means that Isabel and Jamie can each pursue their somewhat erratic work schedules. Jamie, a bassoonist, plays in area ensembles and also gives music lessons to school age pupils. For her part, Isabel continues to manage and edit the prestigious specialty publication Journal of Applied Ethics. She owns this journal – after a considerable struggle – and is justifiably proud of it.

For the past two weeks, I’ve been happily marinating in the works of Alexander McCall Smith. To begin with, I just finished The Geometry of Holding Hands, the latest entry in the Isabel Dalhousie series. Isabel and her beloved Jamie are happily married and now the parents of two little boys, Charlie and Magnus. The dependable presence of Grace, housekeeper and now also child minder, means that Isabel and Jamie can each pursue their somewhat erratic work schedules. Jamie, a bassoonist, plays in area ensembles and also gives music lessons to school age pupils. For her part, Isabel continues to manage and edit the prestigious specialty publication Journal of Applied Ethics. She owns this journal – after a considerable struggle – and is justifiably proud of it.

Isabel also helps out in the delicatessen owned and run by her niece Cat. She fills in when Cat needs an extra pair of hands, frequently performing this service at short notice and with no pay. She enjoys the work, but does feel taken advantage of at times. Jamie also feels this way, on her behalf. The fact that Jamie is actually a long-ago discarded boyfriend of Cat’s can still create awkward situations.

It is, in fact, the fate of Cat’s delicatessen and that of Cat herself that are central to the story. Cat, as anyone knows who has followed this series, is a demanding and difficult person. But she is Isabel’s niece, her only remaining family nearby, someone she feels obligated to care about and watch out for.

Meanwhile, all the hallmarks of McCall Smith’s novels are present here in abundance: graceful writing, humor, insights into Scottish language and customs, and above all, the consideration of questions of morality – the rightness of our actions and feelings.

Oh and there are references to various cultural figures. I was surprised and pleased by the mention of Gertrude Himmelfarb, “the American historian.” In 2012, an essay by Himmelfarb entitled “The Once-Born and the Twice-Born” appeared in the Wall Street Journal. It had an extremely profound effect on my religious thinking. To put it more colloquially, I found it mind-boggling. (If the above link doesn’t work for you, trying accessing the Wall Street Journal through ProQuest, which might be available on your local library’s website. It is on ours.)

As usual, McCall Smith takes us deep into the heart and soul of Isabel Dalhousie:

Do I believe in God? she asked herself. She hated being asked that question by others, but was just as uncomfortable asking it of herself. The problem was that sometimes she said yes, and sometimes no. Or answered evasively, in a way that enabled her to continue to believe in spirituality and its importance, and kept her from the soulless desert of atheism.

‘The soulless desert of atheism’…aye, there’s the rub! Actually, she might profit from a reading of the Himmelfarb essay I referenced above.

Yet always, there is the consolation of the otherworldly beauty of Scotland, as described in the title of this post. And also this:

In a few weeks’ time the solstice would be with them, that perfect moment between what had been and what was to come. It would barely get dark then at these northern latitudes, even at midnight; now the sun was still painting the roofs golden at eight o’clock, a gentle presence, a visitor to a Scotland that was more accustomed to short days and wind and drifting, omnipresent rain. And yet was so beautiful, thought Isabel, so beautiful as to break the heart.

While I was immersed in this novel, I’ve also been preparing to lead a discussion of another McCall Smith novel, The Department of Sensitive Crimes. This is the first in yet another series set in Sweden and featuring Detective Ulf Varg. More on this, following the discussion (to be held via Zoom, of course), but I want to conclude with a snatch of dialog that brought me up short and then made me smile. A contentious married couple, Angel and Baltser, are part of a case Detective Varg is investigating. They are arguing about whether the spa that they’re struggling to make a go of might have ghosts on the premises:

“I think the place might be haunted,” she said. “There might be one of those…what do you call those things? Polter…”

“Poltergeists,” said Ulf.

“Yes, one of those.”

Baltser shook his head. “Nonsense,” he said. “Ghosts don’t exist.”

Angel gave him a sharp look. “How do you know?” she asked. “If you’ve never seen one, how do you know they don’t exist?

Baltser frowned. “I can’t see how to answer that question,” he said.

Angel clearly felt that her point had been made. “Well, there you are.”

A book that shouldn’t have interested me – but it did

By ‘shouldn’t,’ I mean, ‘ordinarily would not have’. But these are anything but ordinary times, as you don’t need me to say.

I got off to slow start with this book, and I wasn’t sure I would stick with it. But I did, and I was ultimately rewarded with a fascinating story beautifully told.

Stanley, a professor of history at Northwestern University, renders the world of that rebellious woman, Tsuneno, so vividly that I had trouble pulling myself back into the present whenever I put the book down.

Marjoleine Kars in her review in the Washington Post

In a sense, Tsuneno inhabits two worlds., The one she is born into in 1804 is called Echigo, a remote village in the snowy countryside of north central Japan. She is the scion of a priestly family, but as a woman, she is almost no control over own life. Instead, she must follow the dictates laid down first by her parents and then by her eldest brother. The world she yearns for, though, is to be found in the storied city of Edo, known since 1868 as Tokyo.

In Edo, Tsuneno believes that she will find at least some measure of freedom. In 1839, she escapes from the strictures of her home life and makes her way to the city of her dreams. And what a place it turns out to be!

I plead utter ignorance of Japanese history, so this book was, among other things, a revelation to me on that subject. Even more, I got so immersed in Tsuneno’s struggles that it was as though I were there with her. I wish I could have helped her; she needed it desperately.

Before I leave this subject, I have to express my deep admiration for the job that Amy Stanley has done in producing this book. The depth of her research can only be described as prodigious.

The great achievement of this revelatory book is to demolish any assumption on the part of English language readers that pre-modern Japan was all blossom, tea ceremonies and mysterious half-smiles. Instead, by working through the rich archive of letters and diaries left by Tsuneno and her family, Stanley reveals a culture that is remarkably reminiscent of Victorian England, which is to say deeply expressive once you’ve cracked the codes.

from the review by Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian. (I should warn potential readers that this review reveals rather a lot about the book’s contents.)

Holder of a doctorate from Harvard, Amy Stanley is currently an associate professor of history at Northwestern University

The colorful world of early nineteenth century Edo contains, among its other attractions, a lively theater scene. I found this film of kabuki on YouTube. I remember many years ago when Grand Kabuki appeared at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC and caused a sensation. I went to a performance. I wish I remember more of what I saw; I just recall being astonished, like everyone else. It was so strange and exotic, and the stagecraft alone was amazing.

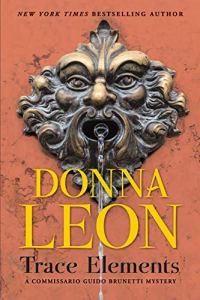

‘…gossip and insinuation, those Venetian twins of truth.” – Trace Elements by Donna Leon

I enjoyed the latest novel by Donna Leon, as I knew I would. In this one, the police are dealing with some chronic pickpockets; they are caught, punished, and then go on plying their trade as before. A more serious case involves a dying woman, Benedetta Toso, whose husband was recently killed in a motorcycle accident. She has expressed an urgent need to talk to the police about what happened to her husband.

I enjoyed the latest novel by Donna Leon, as I knew I would. In this one, the police are dealing with some chronic pickpockets; they are caught, punished, and then go on plying their trade as before. A more serious case involves a dying woman, Benedetta Toso, whose husband was recently killed in a motorcycle accident. She has expressed an urgent need to talk to the police about what happened to her husband.

Commissario Guido Brunetti and his colleague Commissario Claudia Griffoni go to the hospice where Signora Toso is currently being cared for, in order to hear what she has to say. But she is only able to gasp out a few words before she too is overtaken by death.

Being present at the passing of the Signora is emotionally devastating for both Brunetti and Griffoni. It strengthens their resolve to work jointly to get to the bottom of the case.

Once again, the city of Venice gleams in the prose of Donna Leon. I would have liked to spend more time with Brunetti’s family: his children, Raffi and Chiara, who are fast leaving childhood behind, and his wife, the fiery and uncompromising Paola, a professor of English who has a highly laudable specialty in the novels of Henry James.

Nevertheless, a most enjoyable read. Leon’s writing is a joy, filled as it is with classical allusions:

Like Nausicaa listening at her father’s court to Ulysses’ account of his travels, Signorina Elettra sat enthralled.

Last year, Donna Leon was interviewed in the New York Times Book Review’s feature ‘By the Book.’ When asked how she first got hooked on crime fiction, she said this:

Ross Macdonald impressed me for the quality and beauty of his writing. I still, reading through them, come upon passages, especially his descriptions of characters, that I wish I had the courage to steal. He’s also a master at the well-honed plot that takes Lew Archer, and thus the reader, back a generation to find the source of the crime. He’s compassionate, apparently well read, and decent.

I was, of course, no end pleased by this. It’s most gratifying when the writers you esteem praise one another.

Donna Leon is 78 years old or thereabouts; she now divides her time between Venice and Switzerland. I wish her well, and of course I look forward to more novels featuring the investigations of Commissario Guido Brunetti.

‘Another silence, broken by the sound of waves and the long call of gulls.’ – The Long Call by Ann Cleeves

When I first found out that Ann Cleeves was starting yet another series, I was dismayed. I want more Vera! I moaned to myself (and to anyone else within range). I was ready to give this book a pass, only the reviews were so exemplary that I changed my mind.

When I first found out that Ann Cleeves was starting yet another series, I was dismayed. I want more Vera! I moaned to myself (and to anyone else within range). I was ready to give this book a pass, only the reviews were so exemplary that I changed my mind.

Also I was desperate for a British police procedural with some depth, and I was pretty sure I could depend on Cleeves to deliver. I was right.

This protagonist of this series is Matthew Venn. Estranged from his own parents, he lives with his husband Jonathan in a cottage in North Devon. They are well suited, and happy together. But Matthew’s vocation as detective places heavy demands on his time, and on his attention. The Long Call is the story of a mysterious death, the investigation of which becomes increasingly tangled as Matthew pursued various leads. The cast of characters includes several artists, as well as others whose lives have crossed at some point with that of the victim. They are each interesting people in their own right.

The author has placed an open letter to her readers before the novel actually begins. It begins with a statement that is almost a plea for patience and understanding:

…I feel nervous introducing Matthew Venn to you, almost like a teenager bringing a new girlfriend or boyfriend home for the first time.

Cleeves also explains that she spent a large part of her childhood in North Devon and so is happy to be back there and writing about it. On the page opposite this letter is a map of the region, a courtesy deeply appreciated by many readers. One of the strong points of this very strong novel is the vivid way in which Cleeves portrays this setting.

Ann Cleeves has a great way of enlarging on a person’s character by showing how he or she reacts to an particular situation. Here Jen Rafferty, Matthew’s second-in-command, is being shown the rooms in a church where group therapy takes place:

There were posters on the walls, semi-religious imagery of rainbows and doves, slogans about taking power, and loving the inner you. Here it seemed hope and the possibility of redemption abounded. It made Jen feel like punching someone.

In the most recent issue of Deadly Pleasures Mystery Magazine, critic Kristopher Zgorski says this:

As far as titles go, The Long Call works so well because it not only harkens to the bird-watching elements that so often play a part in the works of Ann Cleeves, but in this case it also speaks to the long reach of trauma and the toxic legacy of conspiracy and cover-up at the heart of this book.

Zgorski also reveals the welcome news that this work has already optioned for television. If the result is as good as the Vera series and the Shetland Island series featuring Jimmy Perez, then we have much to look forward to.

Oh – and there is another Vera in the works: The Darkest Evening, due out September 8.

***********************

This is probably as good a place as any to mention that the issue if Deadly Pleasures to which I’ve just alluded is the last one that will appear in hard copy. I very much regret this change, but I understand the necessity. The magazine is a terrific resource for fans of crime fiction. For more information, visit the newly revamped Deadly Pleasures website. To begin a subscription, see this link.

Reading in a roundabout manner

Most Thursdays in the Washington Post there appears a column by Michael Dirda in which an unusual book or literary trend is profiled. These pieces are always worthy of attention. This past Thursday’s, for instance, concerned the classic Japanese tradition of the locked room in crime writing. One of Dirda’s recommendations is a collection of short stories by Tetsuya Ayukawa; these were written between 1954 and 1961, and the book containing them is called The Red Locked Room.  So I’ve now read the first story, “The White Locked Room,” and found it most cunning. Currently, I’m part of the way through the next story, which is quite a bit longer. It’s called “Whose Body” (a title that of course at once put me in mind of the first Lord Peter Wimsey novel of the same title.) I’m enjoying these tales a great deal.

So I’ve now read the first story, “The White Locked Room,” and found it most cunning. Currently, I’m part of the way through the next story, which is quite a bit longer. It’s called “Whose Body” (a title that of course at once put me in mind of the first Lord Peter Wimsey novel of the same title.) I’m enjoying these tales a great deal.

Meanwhile, the volume’s title put me in mind of a classic American mystery that I read recently. It’s called The Red Right Hand by Joel Townsley Rogers, a writer previously not known to me. Wikipedia tells us that Rogers “…was an American writer who wrote science fiction, air-adventure, and mystery stories and a handful of mystery novels.”

This novel is one of a series called American Mystery Classics currently being issued by Otto Penzler. Mr. Penzler, proprietor of New York City’s venerable Mysterious Bookshop, can be depended upon to further the interest in, and appreciation of, crime fiction among the general populace. In launching this excellent series (with, I might add, its delightful covers), he is doing all of us mystery lovers a great service.

This novel is one of a series called American Mystery Classics currently being issued by Otto Penzler. Mr. Penzler, proprietor of New York City’s venerable Mysterious Bookshop, can be depended upon to further the interest in, and appreciation of, crime fiction among the general populace. In launching this excellent series (with, I might add, its delightful covers), he is doing all of us mystery lovers a great service.

Right from the get go, The Red Right Hand unnerved me. This is one of the most genuinely bewildering mysteries I’ve ever read. But over and above the strangeness of the plot, there’s a feeling of dread that steadily deepens as the story moves forward. The time is just after the Second World War. Dr. Henry Riddle, a young surgeon from New York City, is driving upstate when he encounters a young woman in desperate need of help. She and her fiance, Inis St. Erme, had been on their way to Connecticut to get married when they picked up a hitchhiker. This strange little man seemed harmless enough – until he wasn’t. He had attacked Inis and made off with their vehicle. She herself had barely managed to escape before they drove off.

What happens next is…well, you need to read it and experience it for your self. Meanwhile, here is what e Booklist reviewer Emily Melton says:

When the full story is finally revealed in this disturbing nightmare of a whodunnit, it will well leave readers reeling. A must-read masterpiece, thankfully resurrected.

‘The not-knowing is mad-making.’ The Cold Vanish: Seeking the Missing in North America’s Wildlands, by Jon Billman

This is a book about persons who disappear, primarily those who go missing in the wilder regions of the Pacific Northwest. Typically, they have set off alone on a journey into one of these remote places, and, at some point, have ceased to provide evidence of their whereabouts. Family and friends become concerned, then frantic. Various rescue organizations launch searches. The aforementioned family and friends often do the same, if they can.

This is a book about persons who disappear, primarily those who go missing in the wilder regions of the Pacific Northwest. Typically, they have set off alone on a journey into one of these remote places, and, at some point, have ceased to provide evidence of their whereabouts. Family and friends become concerned, then frantic. Various rescue organizations launch searches. The aforementioned family and friends often do the same, if they can.

In the Spring of 2017, Jacob Gray planned a long distance bicycling journey through Olympic National Park in Washington State. In April, Jacob’s red bicycle was found, along with a number of other items, lying beside a trail in the park. The young man’s whereabouts could not be determined. Family, friends, and search and rescue organizations embarked on a search that lasted for well over a year but seemed to go on forever.

Billman tells numerous other tales of persons lost in the wilderness. A few – a very few – end happily, with the lost individual being located before time has run out. One of those stories takes place on Maui, Hawaii, and is particularly harrowing in the retelling.

[Amanda] Eller, who lives in Haiku, ducked down a little side path for a meditation break. When she stood up to continue on the main trail, she got turned around, forgetting which way she’d come in. And as outdoor athletes can and sometimes do, she pushed herself swiftly and confidently in the wrong direction, determined not to backtrack, so that her hourlong outing turned into a seventeen-day bushwhack from hell.

The discovery of Eller while she was still alive, albeit injured in not in great shape, was nothing short of a miracle.

It was the kind of miracle that Jacob Gray’s father never stopped hoping for. And he didn’t just hope – he searched – actively, relentlessly. Helped by many people, Jon Billman among them.

In the course of this book, I learned fascinating facts about some places that I knew almost nothing about:

In Siskiyou County we pass Mount Shasta, which is a legendary now-dormant volcano of myth and magic and missing persons. It rises to 14,179 feet, the second-highest peak in the Cascade Range. The mountain is a sacred site to the Winnemem Wintu tribe, indigenous to the area, as well as the Modoc, Achomawi, Atsuwegi, and Shasta peoples. Bigfoot has been seen here for years—dozens of them. Some Native Americans claim a species of tiny, evil people live above the treeline on Mount Shasta and throw rocks at humans who get too close.

And there is more about this fabled peak.

But The Cold Vanish is primarily about people who disappear in the wilderness, and the desperate attempts of their loved ones and others to locate them.. These stories are mesmerizing. Most of them are also heartbreaking. But they are so filled with acts of heroism and selflessness that are inspiring and humbling. Above all, I am grateful to have met, even at a remove, Randy Gray. Greater love hath no father; I admire him tremendously. And I hope that he has found some measure of peace.

This was a tough review for me to write. There was a considerable spillover of grief. In an effort to console myself, I made a donation to Pacific Northwest Search and Rescue. In the ‘Notes’ field, I said that I was making this donation in honor of Jacob Gray and Randy Gray.