1979

Allie Burns is young, ambitious, and smart. She wants desperately to make it as an investigative reporter. For the time being, she’s on the staff of a small regional paper The Clarion of Glasgow. She considers this position a stepping stone that will lead, hopefully, to a position with a major news organization.

Allie Burns is young, ambitious, and smart. She wants desperately to make it as an investigative reporter. For the time being, she’s on the staff of a small regional paper The Clarion of Glasgow. She considers this position a stepping stone that will lead, hopefully, to a position with a major news organization.

Meanwhile, she finds a congenial colleague in Danny Sullivan; both his drive and his goals are similar to hers. Together, they embark on a story about tax fraud that targets some heavy hitters. After scoring with this investigation, Allie and Danny decide to go after bigger fish. and then bigger – until….

You’ll have to read it to find out.

Val McDermid has based this story on her own experiences as a young journalist – ‘journo,’ as I often see them called in British crime fiction. It has a ring of authenticity. The other Clarion reporters come across as genuine and believable. But it’s Allie and Danny’s show, that’s for sure. They’re enthusiastic, resourceful, and above all, just plain gutsy. This is the start of a new series; I for one am eager to follow Allie on her (sometimes harrowing) adventures.

In the course of this narrative, McDermid pays tribute to some of the great writers in the crime fiction field, both past and present. At one point, Allie, in need of some good reading material, finds just the thing in a nearby bookstore: Judgement in Stone by Ruth Rendell. YES!!!

‘This was machair, that quintessentially Hebridean landscape–part beach, part sand dune, part field of tiny flowers.’ – The Geometry of Holding Hands, by Alexander McCall Smith

For the past two weeks, I’ve been happily marinating in the works of Alexander McCall Smith. To begin with, I just finished The Geometry of Holding Hands, the latest entry in the Isabel Dalhousie series. Isabel and her beloved Jamie are happily married and now the parents of two little boys, Charlie and Magnus. The dependable presence of Grace, housekeeper and now also child minder, means that Isabel and Jamie can each pursue their somewhat erratic work schedules. Jamie, a bassoonist, plays in area ensembles and also gives music lessons to school age pupils. For her part, Isabel continues to manage and edit the prestigious specialty publication Journal of Applied Ethics. She owns this journal – after a considerable struggle – and is justifiably proud of it.

For the past two weeks, I’ve been happily marinating in the works of Alexander McCall Smith. To begin with, I just finished The Geometry of Holding Hands, the latest entry in the Isabel Dalhousie series. Isabel and her beloved Jamie are happily married and now the parents of two little boys, Charlie and Magnus. The dependable presence of Grace, housekeeper and now also child minder, means that Isabel and Jamie can each pursue their somewhat erratic work schedules. Jamie, a bassoonist, plays in area ensembles and also gives music lessons to school age pupils. For her part, Isabel continues to manage and edit the prestigious specialty publication Journal of Applied Ethics. She owns this journal – after a considerable struggle – and is justifiably proud of it.

Isabel also helps out in the delicatessen owned and run by her niece Cat. She fills in when Cat needs an extra pair of hands, frequently performing this service at short notice and with no pay. She enjoys the work, but does feel taken advantage of at times. Jamie also feels this way, on her behalf. The fact that Jamie is actually a long-ago discarded boyfriend of Cat’s can still create awkward situations.

It is, in fact, the fate of Cat’s delicatessen and that of Cat herself that are central to the story. Cat, as anyone knows who has followed this series, is a demanding and difficult person. But she is Isabel’s niece, her only remaining family nearby, someone she feels obligated to care about and watch out for.

Meanwhile, all the hallmarks of McCall Smith’s novels are present here in abundance: graceful writing, humor, insights into Scottish language and customs, and above all, the consideration of questions of morality – the rightness of our actions and feelings.

Oh and there are references to various cultural figures. I was surprised and pleased by the mention of Gertrude Himmelfarb, “the American historian.” In 2012, an essay by Himmelfarb entitled “The Once-Born and the Twice-Born” appeared in the Wall Street Journal. It had an extremely profound effect on my religious thinking. To put it more colloquially, I found it mind-boggling. (If the above link doesn’t work for you, trying accessing the Wall Street Journal through ProQuest, which might be available on your local library’s website. It is on ours.)

As usual, McCall Smith takes us deep into the heart and soul of Isabel Dalhousie:

Do I believe in God? she asked herself. She hated being asked that question by others, but was just as uncomfortable asking it of herself. The problem was that sometimes she said yes, and sometimes no. Or answered evasively, in a way that enabled her to continue to believe in spirituality and its importance, and kept her from the soulless desert of atheism.

‘The soulless desert of atheism’…aye, there’s the rub! Actually, she might profit from a reading of the Himmelfarb essay I referenced above.

Yet always, there is the consolation of the otherworldly beauty of Scotland, as described in the title of this post. And also this:

In a few weeks’ time the solstice would be with them, that perfect moment between what had been and what was to come. It would barely get dark then at these northern latitudes, even at midnight; now the sun was still painting the roofs golden at eight o’clock, a gentle presence, a visitor to a Scotland that was more accustomed to short days and wind and drifting, omnipresent rain. And yet was so beautiful, thought Isabel, so beautiful as to break the heart.

While I was immersed in this novel, I’ve also been preparing to lead a discussion of another McCall Smith novel, The Department of Sensitive Crimes. This is the first in yet another series set in Sweden and featuring Detective Ulf Varg. More on this, following the discussion (to be held via Zoom, of course), but I want to conclude with a snatch of dialog that brought me up short and then made me smile. A contentious married couple, Angel and Baltser, are part of a case Detective Varg is investigating. They are arguing about whether the spa that they’re struggling to make a go of might have ghosts on the premises:

“I think the place might be haunted,” she said. “There might be one of those…what do you call those things? Polter…”

“Poltergeists,” said Ulf.

“Yes, one of those.”

Baltser shook his head. “Nonsense,” he said. “Ghosts don’t exist.”

Angel gave him a sharp look. “How do you know?” she asked. “If you’ve never seen one, how do you know they don’t exist?

Baltser frowned. “I can’t see how to answer that question,” he said.

Angel clearly felt that her point had been made. “Well, there you are.”

Best of 2018, Nine: Crime fiction, part two

“After the demise of the UK’s queens of crime, P.D. James and Ruth Rendell, only one author could take their place: the Scottish writer Val McDermid….”

The Guardian

I’m aware there are those who would dispute this assertion. But after reading Broken Ground, I’m on board with it. I absolutely loved this book.

I’d previously only read two novels by Val McDermid: A Place of Execution (2000) and The Grave Tattoo (2006). Those are both standalones. Broken Ground, on the other hand, is the fifth novel in the Karen Pirie series.

How I wish I’d begun at the beginning! Karen Pirie, beleaguered but undaunted, is a hero for our times – my times, anyway. She’s having to come to terms with the loss of her lover, also an officer in the Force. (In this sense, as in some others, she reminded me of Erika Foster in Robert Bryndza‘s excellent series.) She’s human but not superhuman. Not always likeable, but almost always admirable.

I love McDermid’s writing. It is always assured, sometimes even poetic, but it can veer abruptly toward hard hitting. For a novel in which action predominates, there is some striking description. Most likely McDermid can’t help including such passages when writing about her native Scotland, whether city or countryside. (If you’ve been there, you’ll understand why.)

In the course of an investigation, Karen finds herself on rural, alien ground, housed in an odd accommodation:

For a woman accustomed to attacking insomnia by quartering the labyrinthine streets of Edinburgh with its wynds and closes, its pends and yards, its vennels and courts, where buildings crowded close in unexpected configurations, the empty acres of the Highlands offered limited possibilities.

…..

The sky was clear and the light from the half-moon had no competition from the street lights so the pale glow it shed was more than enough to see by. She turned right out of the yurt and followed the track for ten minutes till it ended in a churned-up turning circle by what looked like like the remnants of a small stone bothy. Probably a shepherd’s hut, Karen told herself, based on what she knew was the most rudimentary guess work. The wind had stilled and the sea shimmered in the moonlight, tiny rufflets of waves making the surface shiver. She stood for awhile, absorbing the calm of the night, letting it soothe her restlessness.

I feel deeply grateful that there are still people who can write like this. I’m equally grateful that police procedurals of this caliber are still being written.

While researching Val McDermid, I came upon a gracious memorial she composed on the occasion of the passing of Colin Dexter, creator of the inimitable Inspector Morse.

Sir John Lister-Kaye on tawny owls and willow warblers

Throughout my reading of Gods of the Morning, I’ve been astonished over and over again by Lister-Kaye’s gorgeous descriptions:

Throughout my reading of Gods of the Morning, I’ve been astonished over and over again by Lister-Kaye’s gorgeous descriptions:

Like molten gold from a crucible, the first touch of sun spilled in from the east, from the glistening horizon of the Moray Firth, so bright that I couldn’t look at it, flooding its winter fire up the river, right past me and on up the valley. The river trailed below me, like a silk pashmina thrown down by an untidy teenager. Strands of mist over the water were fired with yellow flame, as though part of some mysterious ritual immolation. The new-born light raked the steep glen sides, floodlighting every rocky prominence and daubing deep craters of black shadow so that the familiar shape of the land vanished before my eyes. I was in a wonderland, strange to me and a little unnerving. The dogs sat uncharacteristically silent at my feet, noses lifting to test the air, but stilled as though they, too, could sense the moment.

And yet, even in the midst of all this beauty, there appear certain disturbing vignettes. One concerns an almost sacrilegious act committed by Lister-Kaye when he was eleven years old.

His grandfather had shown him the customary roosting place of a tawny owl in a yew tree on the family property. Earlier that year, young John had been gifted with an air rifle:

It was the most exciting birthday gift I had ever received. In the short space of a birthday afternoon I became Davy Crockett, Kit Carson and the Lone Ranger all rolled into one ill-disciplined puberulous youth bursting to tangle with danger and adventure.

You can probably guess what happened next:

The head-hanging truth that still torments my soul is that when no one was looking I crept out and shot that owl. For a moment it seemed not to move; then it tipped forward and fell like a rag at my feet. I picked it up, hot and floppy in my hands. Its cinnamon and cream mottled plumage was as soft and silky as Angora fleece. One owl, one boy, one gun. Two burst hearts, one with lead, the other with guilt. I had never held a tawny owl before and its lifeless beauty hit me in a withering avalanche of instantaneous remorse and shame. I have never forgotten it and never forgiven myself. To this day I ask myself why I did it.

The very definition of remorse.

Several works came to mind when I read this passage. Foremost among them, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

‘God save thee, ancient Mariner!From the fiends, that plague thee thus!—Why look’st thou so?’—With my cross-bowI shot the ALBATROSS.……………………………………And I had done a hellish thing,And it would work ’em woe:For all averred, I had killed the birdThat made the breeze to blow.Ah wretch! said they, the bird to slay,That made the breeze to blow!

Illustrations for “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Gustave Dore

Surely there is no more dramatic and meaningful moment in life than when you realize that an action you’ve taken – whatever the reason – is profoundly, morally wrong. Almost always that action is an irreparable transgression, against God, nature, or one’s fellow human beings. Sometimes that action involves the taking of a life. In a chapter in A Sand County Almanac entitled “Thinking Like a Mountain,” the great conservationist Aldo Leopold recounts such a moment in his own life:

We were eating lunch on a high rimrock, at the foot of which a turbulent river elbowed its way. We saw what we thought was a doe fording the torrent, her breast awash in white water. When she climbed the bank toward us and shook out her tail, we realized our error: it was a wolf. A half-dozen others, evidently grown pups, sprang from the willows and all joined in a welcoming melee of wagging tails and playful maulings. What was literally a pile of wolves writhed and tumbled in the center of an open flat at the foot of our rimrock.

In those days we had never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack, but with more excitement than accuracy: how to aim a steep downhill shot is always confusing. When our rifles were empty, the old wolf was down, and a pup was dragging a leg into impassable slide-rocks.

We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes – something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

John Lister-Kaye’s sense of wonder at the nesting and migratory habits of birds – indeed, at their very existence – shines throughout in Gods of the Morning.

A willow warbler (Phylloscopus trochilus – the cascading leaf-watcher) is an unexceptional little bird, often our first summer migrant, an arrival announced by the male birds rendering a rippling, descending peal of pure notes tinged with mild complaint, but as pretty as a summer waterfall. It’s a refrain that rings through the spring woods, repeating over and over again, lifting to a brief, pleading crescendo, then slowing as it falls and, diminuendo, fades away at the end. It seems to be calling out, ‘Now that I’ve arrived, what am I going to do?’

…………………………………………..

Like the blackcap, it resides in that large family of typical warblers that come and go every summer without any fuss, unnoticed except by ornithologs like me and a few thousand binocular-toting others to whom these tiny creatures assume an importance far greater than their size. If they’ve heard of a willow warbler at all, the vast generality of people don’t know that it has just completed a global marathon, back from wintering in southern Africa, a migration of three thousand miles of skimming arid plains, dodging desert sandstorms and leap-frogging seas and mountains, and they probably wouldn’t care much either. ‘All little brown birds are the same to me,’ I’m told, over and over again. But not to me: for me they all carry meaning and I thirst to know more. Sylviidae, the family.

I’m here to tell you, it takes a rapturous devotion like Lister-Kaye’s to keep all this warbler lore straight! But if anyone can do it, he can.

Reading this skilled and eloquent observer’s descriptions of his almost mystical encounters with avian species put me in mind of a piece I read some years ago: Loren Eiseley‘s “The Judgment of Birds.” There’s a bit in this essay about a close encounter with a crow that has remained vivid in my imagination:

This crow lives near my house, and though I have never injured him, he takes good care to stay up in the very highest trees and, in general, to avoid humanity.

His world begins at about the limit of my eyesight.

On the particular morning when this episode occurred, the whole countryside was buried in one of the thickest fogs in years. The ceiling was absolutely zero. All planes were grounded, and even a pedestrian could hardly see his outstretched hand before him.

I was groping across a field in the general direction of the railroad station, following a dimly outlined path. Suddenly out of the fog, at about the level of my eyes, and so closely that I flinched, there flashed a pair of immense black wings and a huge beak. The whole bird rushed over my head with a frantic cawing outcry of such hideous terror as I have never heard in a crow’s voice before and never expect to hear again.

He was lost and startled, I thought, as I recovered my poise. He ought not to have flown out in this fog. He’d knock his silly brains out.

All afternoon that great awkward cry rang in my head. Merely being lost in a fog seemed scarcely to account for it—especially in a tough, intelligent old bandit such as I knew that particular crow to be. I even looked once in the mirror to see what it might be about me that had so revolted him that he had cried out in protest to the very stones.

Finally, as I worked my way homeward along the path, the solution came to me.

It should have been clear before. The borders of our worlds had shifted. It was the fog that had done it. That crow, and I knew him well, never under normal circumstances flew low near men. He had been lost all right, but it was more than that.

He had thought he was high up, and when he encountered me looming gigantically through the fog, he had perceived a ghastly and, to the crow mind, unnatural sight.

He had seen a man walking on air, desecrating the very heart of the crow kingdom, a harbinger of the most profound evil a crow mind could conceive of—air- walking men. The encounter, he must have thought, had taken place a hundred feet over the roofs.

********************************

At the conclusion of Coleridge’s poem, the mariner offers this moral:

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.He prayeth best, who loveth bestAll things both great and small;For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

“Did ever raven sing so like a lark, / That gives sweet tidings of the sun’s uprise?” Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus

In John Lister-Kaye’s Gods of the Morning, these lines appear above the chapter entitled, “The Gods of High Places” (chapter 8).

In John Lister-Kaye’s Gods of the Morning, these lines appear above the chapter entitled, “The Gods of High Places” (chapter 8).

Lister-Kaye – i.e. Sir John Philip Lister Lister-Kaye, 8th Baronet OBE – is inordinately fond of crows, rooks, ravens – those avian species subsumed under the genus Corvus. He studies them at Aigas, the Field Study Center in the Scottish Highlands which he founded in 1977. He lives and works there; it is his calling and his life’s work. What a lucky man! (You can read in the Wikipedia entry how he made this “luck” happen.)

There is nothing dull about a raven. As glossy as a midnight puddle, bigger than a buzzard, with a bill like a poleaxe and the eyes of an eagle, its brain is as sharp and quick as a whiplash. Surfing the high mountain winds, ravens tumble with the ease and grace of trapeze artists, and their basso profondo calls are sonorous, rich and resonant, gifting portent to the solemn gods of high places. Ravens surround us at Aigas, and they nest early.

Most of us consider crows a sort of nuisance bird, and anyway too common to be of any great interest. Lister-Kaye gently seeks to disabuse us of that notion.

The advent of wildlife tourism as an economic force, legal protection and a wider conservation understanding has permitted raven numbers to increase and the birds to nest at least in some areas, unmolested. They are now part of our daily lives. I listen out for the guttural ‘cronk, cronk’ as they pass overhead every day. If a solitary black bird rows into view (rooks are almost never solitary), I stop what I’m doing to look for the wedge-shaped tail or to get the measure of its bulk to distinguish it from carrion or hooded crows. As the years have flicked by, their daily appearance here, their criss-crossing of the glen from high moor to hill, has become predictable, a reassuring norm, something we note with pleasure, and a characterful addition to our resident avifauna.

Confident of that interest, as a chunky silhouette crosses or that unmistakable plunking call reverberates from the woods, I don’t hesitate to point and call to my friends and field centre colleagues, ‘Ha! Raven!’, yet I find myself still wary of my audience. Those farmers and crofters aplenty who charge ravens with killing lambs and many, not just old-school, gamekeepers are quick to condemn all crows, but especially hoodies and ravens, and will still do their utmost to kill them. ‘The croaking raven doth bellow for revenge.’ (Hamlet, Act III, scene ii.)

As you’ve already no doubt noted, Shakespeare makes frequent mention of the raven. My favorite instance of this occurs in MacBeth, when Lady MacBeth gives vent to her ghoulish pleasure at Duncan’s arrival:

The raven himself is hoarseThat croaks the fatal entrance of DuncanUnder my battlements.

I’ll close with a photo taken by my son Ben Davis at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, a nature lover’s paradise that probably has some aspects in common with the Aigas Field Centre.

[Click to enlarge]

Rapturous description…

…of a beautiful place. Here’s how it begins:

In 1976 I set up a field studies centre here at Aigas, an ancient site in a glen in the northern central Highlands – it was Scotland’s first. It is a place cradled by the hills above Strathglass, an eyrie looking out over the narrow floodplain of the Beauly River. Aigas is also my home. We are blessed with an exceptionally diverse landscape of rivers, marshes and wet meadows, hill grazings, forests and birch woods, high moors and lochs, all set against the often snow-capped four-thousand-foot Affric Mountains to the west. Golden eagles drift high overhead, the petulant shrieks of peregrines echo from the rock walls of the Aigas gorge, ospreys hover and crash into the loch, levering themselves out again with a trout squirming in their talons’ fearsome grip. Red squirrels peek round the scaly, rufous trunks of Scots pines, and, given a sliver of a chance, pine martens would cause mayhem in the hen run. At night roe deer tiptoe through the gardens, and in autumn red deer stags surround us, belling their guttural challenges to the hills. Yes, we count our blessings to be able to live and work in such an elating and inspiring corner of Britain’s crowded isle.

(All I could think when I read this was that I wanted to pack my bags at once and go there.)

The above passage is from Gods of the Morning: A Bird’s-Eye View of a Changing World, by John Lister-Kaye (that’s Sir John Lister-Kaye, 8th Baronet OBE. I admit it: I’m a sucker for British titles, though the gentleman himself declines to make mention of it in this context.)

Admittedly, I have a poor track record when it comes to finishing books about the natural world (although I have a great track record for starting them). Nevertheless, this one bids fair to being an exception. I’m off to a good start. The writing is maintaining a high standard of gorgeousness.

I’ve got my fingers crossed…

**************************

Here are some views of Aigas:

How one envies John Lister-Kaye, secure in his glorious Scottish fastness!

And that has to be one of my all time favorite book covers.

Yet another reason to visit Scotland….

As if there weren’t already a sufficient number –

But really, take a look at this:

And this:

And this:

Behold the kelpies!!

**************************

Click here for the statement by the artist Andy Scott.

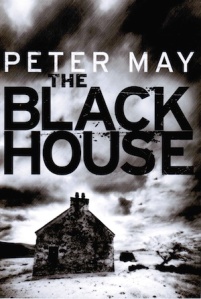

The Blackhouse, by Peter May

The Blackhouse is a big, ambitious novel. Its chief protagonist is Finlay MacLeod is a police officer in Edinburgh. As the novel begins, Fin is investigating a homicide that took place in that city when DCI Black, his boss, suddenly informs him that he’s being sent to the Isle of Lewis in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. It seems that a murder there closely resembles MacLeod’s Edinburgh case as regards the killer’s MO. One other important point: Fin MacLeod was born and raised on the Isle of Lewis.

The Blackhouse is a big, ambitious novel. Its chief protagonist is Finlay MacLeod is a police officer in Edinburgh. As the novel begins, Fin is investigating a homicide that took place in that city when DCI Black, his boss, suddenly informs him that he’s being sent to the Isle of Lewis in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. It seems that a murder there closely resembles MacLeod’s Edinburgh case as regards the killer’s MO. One other important point: Fin MacLeod was born and raised on the Isle of Lewis.

Fin has not been back to Lewis for a long time. There are reasons for his lengthy absence. He has no living family members still on the island. But he does have friends, a former lover, and other associations still there. The woman he had loved, and known from childhood, was called Marjorie – Marsaili in Gaelic, pronounced Marshally in that language. Fin’s best friend had been Artair Macinnes. Artair and Marsaili were now married; they had a son named Fionnlagh, which is Fin’s own Gaelic name. If this sounds like a complex and potentially fraught situation – it is.

Nevertheless, Fin must follow orders and return to Lewis, to look into the murder of Angus Macritchie. In times past, Macritchie had been the archetypal schoolyard bully, disliked by Fin and pretty much everyone else on the island. Now he was dead, and it’s up to Fin to find out who killed him and why.

Meanwhile, Fin’s personal life in Edinburgh has been slowly and painfully disintegrating. He has suffered a terrible bereavement, and his marriage is on the rocks. It’s a good time to get away from Edinburgh. But Fin is apprehensive about returning to the Isle of Lewis – and it turns out, he has good reason to feel that way.

Peter May’s depiction of life on this remote outpost is meticulous and vivid. Here, Fin recalls a moment from his childhood on the island:

The northern part of Lewis was flat and unbroken by hills or mountains, and the weather swept across it from the Atlantic to the Minch, always in a hurry. And so it was always changing. Light and dark in ever-shifting patterns, one set against the other – rain, sunshine, black sky, blue sky. And rainbows. My childhood seemed filled with them. Usually doublers. We watched one that day, forming fast over the peatbog, vivid against the blackest of blue-black skies. It took away the need for words

In a later scene, Fin and a fellow officer are driving up the west coast of the island:

He watched the villages drift by, like moving images in an old family album, every building, every fencepost and blade of grass picked out in painfully sharp relief by the sun behind them. There was not a soul to be seen anywhere….The tiny village primary schools, too, were empty, still shut for the summer holidays. Fin wondered where all the children were. To their right, the peatbog drifted into a hazy infinity, punctuated only by stoic sheep standing firm against the Atlantic gales. To their left, the ocean itself swept in timeless cycles on to beaches and into rocky inlets, , creamy white foam crashing over darkly obdurate gneiss, the oldest rock on earth. The outline of a tanker, like a distant mirage, was just discernible on the horizon.

Peter May’s writing is powerful and persuasive, at times ascending to the poetic. This gift serves him well when he comes to describe an event of supreme importance to the people of Lewis: the guga harvest. Every year, a limited number of men are invited to be a part of this unique island tradition. It begins with a boat trip across treacherous waters to a rocky island called An Sgeir, where thousands of birds arrive during the summer months to nest and procreate. The guga, or gannets, are considered delicacies by the people of Lewis. The job of the guga hunters is to capture some two thousand birds within a two week period. The young chicks are plucked from their nests while the frantic parents flap their wings and screech in protest. The necks of the chicks are quickly broken; then they are plucked clean, slit open to receive sea salt as a preservative, and otherwise made ready for the return trip. Ultimately they will be presented to the islanders of Lewis, perfectly preserved and ready to eat.

It is considered an honor to be selected as a participant in the yearly guga harvest. Fin received just such an honor during his last summer before leaving the island to attend university in Glasgow. It is a distinction he could have well done without. He has no desire to go, but once chosen, it is virtually impossible to decline. And so, with a heavy, heart, he joins the team of hunters. After the inevitable rough crossing Fin catches sight of An Sger for the first time:

Three hundred feet of sheer black cliff streaked with white, rising straight out of the ocean in front of us….I saw what looked like snow blowing in a steady stream from the peak before I realized that the snowflakes were birds. Fabulous white birds with blue-black wingtips and yellow heads, a wingspan of nearly two metres. Gannets. Thousands of them, filling the sky, turning in the light, riding turbulent currents of air.

(The white streaks are actually bird guano. Fin had smelled An Sgeir before he’d seen it.)

An Sgeir was barely half a mile long, its vertebral column little more than a hundred yards across. There was no soil here, no grassy banks or level land, no beaches. Just shit-covered rock rising straight out of the sea.

Fin adds that he couldn’t imagine a more inhospitable place. But this is just the beginning. While engaged in the arduous labor of unloading two weeks’ worth of supplies, Fin discovers how hard it is to maintain your footing on the island. The rock is made slick not just by the guano but by the slimy green vomit produced by petrel chicks terrified by this sudden human invasion. Add to that the unceasing racket generated by the avian multitudes, and you have a sort of Hell on Earth. And there they will stay for two full weeks, carrying out the multifaceted operation of catching, killing, and preparing the birds.

There is only one place to shelter on An Sgeir. It is a blackhouse.

Although Fin can’t help but admire the ingenuity, resourcefulness, and just plain toughness of the guga hunters, he finds the two weeks on An Sgeir an awful experience, an endurance test that can’t end soon enough. And at the end of two weeks it does end. But not without two momentous occurrences, the full import of which Fin does not grasp until many years after the event.

************************

Peter May’s evocation of life on the Isle of Lewis is deeply resonant. The geography of the place, the social order, the dominance of the church, the entire way of life – all are presented here in minute detail. There were times when I thought it might be too minute. The anthropology threatens to overwhelm the mystery. The actual crime was, for this reader, the least memorable aspect of the book. The cast of characters is fairly large; moreover, the complex narrative alternates between the present and the past. This brings up a certain aspect of the narrative style employed by May in this novel: the events of the present time are set forth in the third person, while the sections dealing with Fin’s boyhood on the island are recounted by him in the first person. It took me a while to get comfortable with this method of advancing the story.

Until I read The Blackhouse, the only knowledge I had of the Isle of Lewis had to do with the famous Chessmen, almost certainly carved by Norsemen in the early Middle Ages and discovered on the island in 1831. (In the novel, Fin recalls a bit of island legend to the effect that the crofter who found the tiny carvings, mistaking them for the “…elves and gnomes, the pygmy sprites of Celtic folklore,” fled the scene in fear for his life.)

Until I read The Blackhouse, the only knowledge I had of the Isle of Lewis had to do with the famous Chessmen, almost certainly carved by Norsemen in the early Middle Ages and discovered on the island in 1831. (In the novel, Fin recalls a bit of island legend to the effect that the crofter who found the tiny carvings, mistaking them for the “…elves and gnomes, the pygmy sprites of Celtic folklore,” fled the scene in fear for his life.)

Peter May’s description of the guga harvest is riveting and bizarre to the point of almost seeming hallucinatory. Off hand, as regards its affect on the reader – this reader, anyway – the only recent fiction I can readily compare it to is Karen Russell’s astonishing story “St. Lucy’s School for Girls Raised by Wolves.” So – is there actually such a thing as the guga harvest? Indeed there is, as you will see if you click here.

There are actual blackhouses remaining in the Outer Hebrides, although few if any still serve as dwelling places. Here is Fin’s description:

The Blackhouses had dry-stone walls with thatched roofs and gave shelter to both man and beast. A peat fire burend day and night in the centre of the stone floor of the main room. It was called the fire room. There were no chimneys, and smoke was supposed to escape through a hole in the roof. Of course, it wasn’t very efficient, and the houses were always full of the stuff.

He adds: “It was little wonder that life expectancy was short.” (Wikipedia has an interesting entry on the blackhouses.)

*****************************************

The Blackhouse presents some structural challenges for the reader, and there were times when the plot seemed somewhat labored, if not downright irrelevant, given the fascination of the setting.. But Peter May writes beautifully, and he’s created an enormously likable protagonist in Fin MacLeod. This is the first novel in the Lewis Trilogy, and I look forward to the next one.

Scotland the Brave: Isabel Dalhousie and her circle

Isabel Dalhousie’s mind is a wondrous place in which to spend time. I love the way quotations from her beloved W.H. Auden invariably come to mind on apt occasions. At one point in The Uncommon Appeal of Clouds, she spies a banner reading “We must love one another” draped across the facade of a church. She is immediately put in mind of Auden’s poem “September 1939,” in which the last line of the penultimate stanza is “We must love one another or die.” Auden subsequently altered that line to read “We must love one another and die.” (Italics mine.) He then repudiated the poem altogether, calling it, in Isabel’s words, mendacious. She hastens to add that in her view, the work still retains “a grave beauty.”

Isabel Dalhousie’s mind is a wondrous place in which to spend time. I love the way quotations from her beloved W.H. Auden invariably come to mind on apt occasions. At one point in The Uncommon Appeal of Clouds, she spies a banner reading “We must love one another” draped across the facade of a church. She is immediately put in mind of Auden’s poem “September 1939,” in which the last line of the penultimate stanza is “We must love one another or die.” Auden subsequently altered that line to read “We must love one another and die.” (Italics mine.) He then repudiated the poem altogether, calling it, in Isabel’s words, mendacious. She hastens to add that in her view, the work still retains “a grave beauty.”

In my view, the revised version of the line in question achieves a whole new level of profundity. Click here to read the entire poem, and here for an article that appeared in the New York Times in December of 2001: “Beliefs; After September 11, a 62-year-old poem by Auden drew new attention. Not all of it was favorable.”

The Isabel Dalhousie novels invariably feature expressions of love for Edinburgh and the surrounding countryside. Early in the novel, Isabel finds herself driving out of the city. Her route takes her past Stirling Castle and the monument to William Wallace. It seems that Scottish rugby fans are wont to sing the praises of Wallace, even though his triumph over “the English army of cruel Edward” is seven hundred years in the past. Asking herself why this custom persists, the answer that comes to her first in an unwelcome one: “Because we may not have very much else, apart from our past.” But she immediately rejects this rationale as untrue and unworthy:

We did have a great deal else. We had this land that was unfolding before her now as she turned off towards Doune; these fields and these soft hills and this sky and this light and these rivers that were pure and fresh, and the music that could send shivers of pleasure up the spine and make one so proud of Scotland and of belonging.

She concludes: “We had all that.”

(The musical accompaniment is from Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony.)

As is usual in these novels, the mystery is of a mild nature; though intriguing, it generates little actual suspense. A painting by Nicholas Poussin has been stolen from an avid art collector; a mutual acquaintance enlists the assistance of Isabel, who is herself a collector, primarily of Scottish paintings. In the course of the investigation, she mentions having been to exhibit entitled ‘Poussin and Nature.’ That was in fact an actual exhibit: I saw it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and will never forget it.

Isabel Dalhousie not only thinks deeply, she feels deeply as well. Putting Charlie to sleep, she feels as though she could break down in tears: “…she could have wept for the love of him, as any mother might while watching over her child” (and any grandmother, I might add).

Finally, one of the great pleasures I’ve experienced in following this series is watching the love of Isabel and Jamie grow and mature, seeing Isabel gain confidence in Jamie’s devotion to her, and seeing Jaimie himself increasingly amazed by what a treasure he has in Isabel.

He looked at the clock; Charlie would have to be fetched in half an hour or so. He put his arms about Isabel and embraced her, pulling her to him. Her hands were on his shoulder blades. It was warm in the house and the sound of a mower drifted in from over the road through an open window, bringing with it the smell of cut grass.

*************************

Ron and I were deeply moved and impressed by our 2007 visited to the newly opened Scottish Parliament Building in Edinburgh. I’ll be interested to see if, in upcoming installments in this series, McCall Smith treats specifically of Scotland’s push toward independence. A referendum on the question is scheduled to take place in 2014.

The Charming Quirks of Others: Alexander McCall Smith and the art of fiction

As I fell under the spell yet again, I asked my self, What is it that makes the fiction of Alexander McCall Smith such a glowing and beautiful thing?

As I fell under the spell yet again, I asked my self, What is it that makes the fiction of Alexander McCall Smith such a glowing and beautiful thing?

In The Charming Quirks of Others, Isabel Dalhousie is asked to assist in the process of vetting three candidates for the post of headmaster at a prestigious school for boys. But – no matter; she could be asked to vet three ducks for king of the pond and we’d be equally enchanted. After all, we’re not here because of the detective assignment! There is suspense, of course – there’s always suspense. But that story element has its roots in the mind of our protagonist – and in her heart as well.

One does feel at times vicariously exhausted by Isabel’s unrelenting analysis of the moral dimensions of every situation. Exhausted, yes – but fascinated and stimulated at the same time. Socrates counsels us that the unexamined life is not worth living. No chance of Isabel Dalhousie’s having that problem!

So then: what are the qualities of these novels that make them, for this reader at least, so compelling? First and foremost, the character of Isabel is a marvelous creation. This is a woman for whom the life of the mind is supremely important. But it does not take precedence over matters of the heart. Both have a claim on her and have been known to compete for her time. Isabel also places a high value on the fine arts. She is, in fact, a collector, especially of works by Scottish artists. I knew virtually nothing about these painters until I started reading this series. Now I have several books on the subject. I’m going to insert several works here, just for the sheer joy of gazing at them!

(For more of the same, click here.)

In The Charming Quirks of Others, Isabel is eager to acquire a Raeburn painting in which two of her ancestors appear. She has deep roots in Scotland, a country she loves with unabashed ardor. In fact, each novel in this series is in some way a celebration of the glories of Isabel’s native land (and the author’s too, of course).

Motherhood came late and unexpectedly to Isabel. She had been in the midst of a rapturous affair with Jamie, a young musician. The affair has matured into a committed relationship, strengthened by a mutual adoration of their son Charlie. Here are Jamie and Charlie returning home from an outing:

Charlie had fallen asleep in his pushchair – a tiny bundle of humanity in Macpherson tartan rompers and green shoes. The rompers were damp across the chest with orange juice and childish splutterings; the shoes had a thin crust of mud on them. She smiled; an active morning with his father. She kissed them both: Charlie lightly on his brow so as not to awaken him; Jamie on the mouth, and he held her, prolonging their embrace.

Isabel holds a doctorate in philosophy from Cambridge University. A woman of independent means, she owns and edits a highly regarded professional journal, The Review of Applied Ethics . She and Jamie are engaged to be married. Grace, her housekeeper of long standing, has slipped easily into the role of occasional child minder. On the surface, it would appear that Isabel has as intellectually and emotionally fulfilling a life as a woman could possibly yearn for. And in the main, this is true.

But where Jamie is concerned, Isabel is at times terribly anxious.. He is some fourteen years younger than she, a beautiful youth as well as a gifted musician. She herself is comely and attractive, but she fears that she is no match for the younger women who frequently cross Jamie’s path. Despite his reassurances to the contrary, she feels vulnerable, insecure – and sometimes downright jealous. And you Dear Reader, in the best tradition of great fictional love stories, suffer right along with her.

In The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham, Selina Hastings offers this analysis of the artistry evident in the author’s depiction of Kitty Fane, the protagonist of The Painted Veil. Maugham, says his biographer, “… displays an extraordinary empathy, an ability to create a woman as seen not from a man’s perspective but from that of the woman herself; he completely inhabits and possesses Kitty, knows her from the inside, down to the very nerves and fiber of her being.” This is precisely what Alexander McCall Smith does when he writes about Isabel Dalhousie.

So: what else do I admire about McCall Smith’s fiction? There’s deep insight into the human condition, his realistic depiction of the contradictions in our character that make us what we are. Brilliant, brainy Isabel is as insecure in love as any green school girl. Her vaunted powers of reasoning avail her nothing in the struggle to control her emotions. Strength of will, though, does enable to master her feelings most of the time. Most, but not all. There’s a fraught moment in this novel when she lashes out at Jamie; I confess I was shocked by what she says to him. She regrets her words, of course, the minute they’ve been uttered. As do we all in such circumstances.

I love the way in which Isabel grapples gamely with life’s Big Questions. It is incumbent on her to do this as a philosopher, but this vocation is one she has deliberately chosen, and she never shirks what she sees as her intellectual responsibilities. McCall Smith conveys Isabel’s thought processes as profundity tempered with a touch of irony: “One of the drawbacks to being a philosopher was that you became aware of what you should not do, and this took from you so many opportunities to savor the human pleasure of revenge or greed or sheer fantasising.”

In Isabel’s world, small events can have large implications. At one point, Jamie tells her of an incident from his childhood, when he threw his teddy bear over the Dean Bridge. Isabel finds herself speculating on what could have motivated the child Jamie to fling away a cherished possession:

He was punishing him, no doubt – or perhaps he was punishing himself. And if he was punishing himself, what for? She would ask a psychotherapist friend who knew all about such things. The friend had once said to Isabel that we punish ourselves for all sorts of reasons, but for the most part, we did not deserve it. ‘In fact, Isabel had said, I wonder who truly deserves punishment, anyway. What good does it do to punish a person? All that does is add to the pain of the world.’

Her friend had stared at Isabel. ‘Yes,’ she said. And then, after a further few minutes of thought, she had said yes again. ‘That sounds so right,’ she said. ‘And yet I suspect, Isabel, that you are very wrong.’ And Isabel thought: Yes, I am. She’s right; I’m wrong.

Words or comments casually dropped can initiate a whole new train of thought. Charlie’s childish enunciation of the word “rabbits” – he leaves off the ‘r’ – tickles his mother’s fancy:

Hearing this, Isabel thought of its crossword potential. Cockney customs? Abbits. Senior members of monasteries? Abbits. Not the right thing to do? Bad abbits.

McCall Smith’s descriptions of the city of Edinburgh and the surrounding countryside are worth lingering over. In this scene, Isabel is heading out of the city:

On the drive out she stopped just after Silverburn to watch a bird of prey hunting over the lower slopes of the Pentlands. It was a large hawk, waiting to swoop down on its victim. She drew up at the side of the road and watched as it was mobbed by a flock of smaller birds and ignominiously chased away. The small birds, like tiny spitfires in some unequal, heroic Battle of Britain, twisted and turned in dizzying aerial combat; the hawk, outnumbered and irritated by the onslaught, suddenly flew off towards higher ground and disappeared. Isabel sat for a moment, the engine of the green Swedish car idling, before she resumed her journey. The little battle was so close to the city and yet belonged so completely to another world – as did the man feeding his cattle in the field a mile further along the road, emptying a sack of food into a metal hopper while the cattle thronged about him, jostling for position at the trough.

When Isabel thinks about her love for Jamie, and about what makes the feeling so powerful, she focuses on one exemplary trait:

It is not because you are beautiful; not because I see perfection in your features, in your smile, in your litheness- all of which I do, of course I do, and have done since the moment I first met you. It is because you are generous in spirit; and may I be like that; may I become like you – which unrealistic wish, to become the other, is such a true and revealing symptom of love, its most obvious clue, its unmistakable calling card.

From the specific to the general: spoken like a true philosopher – in this case, a philosopher who is deeply in love.

**********************************************

Alexander McCall Smith will be appearing at the Howard County Library on Sunday April 10, at 6 PM. For information on registration, check the March – May (Spring) issue library’s publication Source, coming out on or around March 1. You can also check the library’s website.