Roberta REALLY Recommends: Uncommon Arrangements: Seven Portraits of Married Life in London Literary Circles 1910-1939, by Katie Roiphe

I just came across a rather intriguing phrase: “ludic reading.” In an article in last week’s Newsweek, “The Future of Reading,” Steven Levy attributes the coinage to Victor Nell, author of Lost in a Book. Ludic reading can be defined as “…that trance-like state that heavy readers enter when consuming books for pleasure.” Those of us who read compulsively will know exactly what Nell is referring to: that state of altered consciousness from which one ultimately emerges blinking, like a mole exposed to sudden sunlight.

I just came across a rather intriguing phrase: “ludic reading.” In an article in last week’s Newsweek, “The Future of Reading,” Steven Levy attributes the coinage to Victor Nell, author of Lost in a Book. Ludic reading can be defined as “…that trance-like state that heavy readers enter when consuming books for pleasure.” Those of us who read compulsively will know exactly what Nell is referring to: that state of altered consciousness from which one ultimately emerges blinking, like a mole exposed to sudden sunlight.

That was me this past Thursday when I finished Uncommon Arrangements. This book was the most delicious fun to read! The seven portraits of married life read rather like extended People Magazine feature pieces, only the celebrities are from the world of letters rather than show business.

The commonality among all the profiles in the book lies in the attempt to broaden the concept of marriage so that it can encompass not only extramarital affairs but sometimes a menage a trois, with everyone living in some degree of amity under the same roof. Why this push toward unconventional lifestyles? The early 1900’s in Britain saw the avant garde in full revolt against Victorian proprieties. This was true in many areas of life, not just the purely personal. but it was in that arena that the gauntlet was most flagrantly thrown down. I found Roiphe’s introduction a tad windy – yes, marriage is an institution full of mysteries and contradictions; I think this is something we can all stipulate. But when she begins describing the lives of her various subjects, the book really takes off.

The first section on H.G. Wells begins with his young mistress, Rebecca West, in the north of England giving birth to his son. Naturally, H.G. is not there; he is with his wife Jane and their children in his country house, Easton Glebe, in Essex. In fact, the husbands in this book have a tremendous talent for not being there for their wives and mistresses. I was quite annoyed at H.G. – that is, until I got to the next chapter on Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry.

The first section on H.G. Wells begins with his young mistress, Rebecca West, in the north of England giving birth to his son. Naturally, H.G. is not there; he is with his wife Jane and their children in his country house, Easton Glebe, in Essex. In fact, the husbands in this book have a tremendous talent for not being there for their wives and mistresses. I was quite annoyed at H.G. – that is, until I got to the next chapter on Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry.

Suffice it to say that John Middleton Murry made H.G. Wells look like a model husband. If ever a woman needed a supportive husband, it was Katherine Mansfield. Yet she and Murry spent most of their married lives apart. What makes this fact especially galling is that Katherine’s health was extremely precarious. To be fair, she wanted her independence as much as he wanted his. They both had literary aspirations, but it was clear from the outset that Katherine was the truly gifted writer. Murry may have genuinely loved her, and been basically well-intentioned, but he comes across in Roiphe’s descriptions of him as weak and self-involved. One thing is certain: his conspicuous absence from Katherine’s life while she became increasingly ill with tuberculosis was unforgivable.

Suffice it to say that John Middleton Murry made H.G. Wells look like a model husband. If ever a woman needed a supportive husband, it was Katherine Mansfield. Yet she and Murry spent most of their married lives apart. What makes this fact especially galling is that Katherine’s health was extremely precarious. To be fair, she wanted her independence as much as he wanted his. They both had literary aspirations, but it was clear from the outset that Katherine was the truly gifted writer. Murry may have genuinely loved her, and been basically well-intentioned, but he comes across in Roiphe’s descriptions of him as weak and self-involved. One thing is certain: his conspicuous absence from Katherine’s life while she became increasingly ill with tuberculosis was unforgivable.

Katherine Mansfield died at age of 34. Roiphe describes the moment in which she succumbs, with Murry, as always, ceding the field to others. It’s a devastating scene.

I was trying to think who it was that John Middleton Murry reminded me of, and then I remembered: Percy Bysshe Shelley. He too did not know what it meant to be a supportive spouse; Mary Shelley’s various tribulations regarding illness and childbirth were usually met by a recitation of his own ailments and complaints. Like Murry, he was not mean-spirited or cruel – just largely useless as a husband.

There were many moments while I was reading this section when I could have cheerfully strangled Murry. What a worthless twit! thought I; surely the worst husband I’m going to encounter in these pages. But… oh no! Next came Frank Russell, older brother of mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell.  Elizabeth Von Arnim had the extreme ill fortune to be wife to this dreadful man. Only it wasn’t really a matter of bad luck, because she knew what he was like and, smart and sophisticated though she was, she married him anyway. Oh well – go figure. Perversity in choices, especially those made by women, is one of the principal themes that emerges repeatedly in these narratives.

Elizabeth Von Arnim had the extreme ill fortune to be wife to this dreadful man. Only it wasn’t really a matter of bad luck, because she knew what he was like and, smart and sophisticated though she was, she married him anyway. Oh well – go figure. Perversity in choices, especially those made by women, is one of the principal themes that emerges repeatedly in these narratives.

One of the many pleasures of this book is the way in which personages from previous chapters put in appearances in later ones. H.G Wells and Rebecca West in particular appear and re-appear. And of course, members of the Bloomsbury group – Clive and Vanessa Bell, Vanessa’s sister Virginia Woolf, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, et. al. – weave their way in and out of the lives of their contemporaries. The chapter on the Bells was positively dizzying; a flow chart might have been useful! Everyone thinks of the drama of the Bloomsbury group playing out in London, but many crucial events in their personal lives occurred in Vanessa and Clive’s country home, Charleston. This house is filled with Vanessa’s exquisite painting. Charleston is profiled, not to mention gorgeously photographed, in the book Historic Arts & Crafts Homes of Great Britain, by Brian D. Coleman.

One can hardly escape the irony of the fact that, despite all their efforts to establish the parameters of what in later years would be called an open marriage, the best intentions of the couples in this book foundered repeatedly as the green-eyed monster reared its ugly, inevitable head. Some basic emotions, it would seem, are virtually impossible to legislate out of the human heart!

In summary, here’s my reaction to the seven portrayals set forth in Uncommon Arrangements:

The most absorbing and intriguing: Jane and H.G. Wells and Rebecca West;

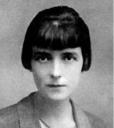

The most complex, richly woven tapestry: Clive and Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and their circle (though I was rather surprised that Roiphe chose not to address the subject of Virginia Woolf’s suicide in this chapter). As I was reading this section of the book, I kept asking myself what attracted all these men to Vanessa Bell; then I found this photograph, and stopped asking…

The most complex, richly woven tapestry: Clive and Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and their circle (though I was rather surprised that Roiphe chose not to address the subject of Virginia Woolf’s suicide in this chapter). As I was reading this section of the book, I kept asking myself what attracted all these men to Vanessa Bell; then I found this photograph, and stopped asking…

The most astonishing: Una Troubridge, Radclyffe Hall, and Evguenia Souline;

The most astonishing: Una Troubridge, Radclyffe Hall, and Evguenia Souline;

The least compelling story: Ottoline and Philip Morrell, though to be fair, the competition was very stiff. (Actually, I thought the most interesting fact about Ottoline Morrell was that she was six feet tall!)

The least compelling story: Ottoline and Philip Morrell, though to be fair, the competition was very stiff. (Actually, I thought the most interesting fact about Ottoline Morrell was that she was six feet tall!)

The most affecting meditation on love and loss: Vera Brittain, George Gordon Catlin, and Winifred Holtby;

The most affecting meditation on love and loss: Vera Brittain, George Gordon Catlin, and Winifred Holtby;

The single most odious character: Frank Russell, hands down! (No picture, and it’s probably just as well).

Finally, the single most poignant and haunting story: Katherine Mansfield.

Finally, the single most poignant and haunting story: Katherine Mansfield.

Katie Roiphe has appended a comprehensive bibliography as well as a fascinating chapter of notes in which she details the voluminous reading and research she did in preparation for the writing of this book. I’m not promising I’ll read them – I never promise anything to anyone regarding what I might read! – but I’m intrigued by the following works:

The Fountain Overflows and The Young Rebecca, by Rebecca West;

The Fountain Overflows and The Young Rebecca, by Rebecca West;

H.G. Wells: Aspects of a Life by Anthony West, Rebecca’s son;

“Mother and Son,” a rather amazing essay by Anthony West in which he heaps vituperation upon his mother (You have to ante up for this. I did, and I sure got my money’s worth!). If you’re curious as to how the children of these irregular unions sometimes fared, West’s piece is a real cautionary tale.

Katherine Mansfield’s short stories (Several, like the devastating “Miss Brill,” are available in full text online.);

Elizabeth and Her German Garden and Enchanted April by Elizabeth Von Arnim;

Elizabeth and Her German Garden and Enchanted April by Elizabeth Von Arnim;

Bloomsbury Recalled, by Quentin Bell;

Bloomsbury Recalled, by Quentin Bell;

The Well of Loneliness, by Radclyffe Hall;

The Well of Loneliness, by Radclyffe Hall;

Radclyffe Hall at the Well of Loneliness: A Sapphic Chronicle, by Lovat Dickson;

Testament of Youth, by Vera Brittain.

Testament of Youth, by Vera Brittain.

Katie Roiphe is the daughter of novelist/memoirist Anne Roiphe; she shares with her mother a rich, fluid prose style. I especially admire this passage in which she comments on Elizabeth Von Arnim’s Enchanted April:

Katie Roiphe is the daughter of novelist/memoirist Anne Roiphe; she shares with her mother a rich, fluid prose style. I especially admire this passage in which she comments on Elizabeth Von Arnim’s Enchanted April:

“In this fantasy that a place will change the deep-seated pattern of a relationship lay a wish: That brusque, moody husbands are literally transformed into tender devoted lovers; that they return to their true selves. What, she was asking herself, would have happened if Russell had changed? In this implausible, lovely, silly romantic universe, one sees much of Elizabeth: a sense of adventure so unusual, a sensitivity to nature so resplendent that it can alter the course of a marriage. There is a beautiful place, a house and garden in the world that can affect its magic on human relations: a vista out to the sea so inspiring that it opens the heart.”

Reading this really made me wish that I could have known Elizabeth Von Arnim. Enchanted April was made into a lovely film in 1992 starring, among others, Miranda Richardson, Jim Broadbent, Joan Plowright, and Michael Kitchen.

Reading this really made me wish that I could have known Elizabeth Von Arnim. Enchanted April was made into a lovely film in 1992 starring, among others, Miranda Richardson, Jim Broadbent, Joan Plowright, and Michael Kitchen.

Finally, there is this memorable line about H.G. Wells: “He was protective of his wife, and did not like her to be abused by his mistresses.”

The art of biography: life stories, and more « Books to the Ceiling said,

August 26, 2008 at 12:44 am

[…] this category: American Bloomsbury by Susan Cheever and Katie Roiphe’s deliciously gossipy Uncommon Arrangements are two […]

Books to talk about – a personal view « Books to the Ceiling said,

March 8, 2010 at 1:25 pm

[…] children for adoption in the decades before Roe v. Wade – Ann Fessler Uncommon Arrangements: seven portraits of married life in London literary circles, 1910-1939 – Katie Roiphe Indian Summer: the secret history of the end of an empire – Alex von Tunzelmann […]

“The literary couple…is a peculiar English domestic manufacture, useful no doubt in a country with difficult winters.”* — Parallel Lives, by Phyllis Rose (with a brief poetical digression) « Books to the Ceiling said,

April 17, 2010 at 12:44 pm

[…] I wonder if Katie Roiphe used Rose’s book as a model for her own highly engaging book, Uncommon Arrangements. […]

“The literary couple…is a peculiar English domestic manufacture, useful no doubt in a country with difficult winters.”* — Parallel Lives, by Phyllis Rose (with a brief poetical digression) « Books to the Ceiling said,

April 17, 2010 at 2:14 pm

[…] I wonder if Katie Roiphe used Rose’s book as a model for her own highly engaging work, Uncommon Arrangements. […]

Mary Douglas said,

December 6, 2011 at 2:41 pm

Roiphe certainly utilized a lot of other people’s work in UNCOMMON ARRANGEMENTS> The Vera Brittain chaper is heavily indebted to the Berry/Bostridge biography from 1995.