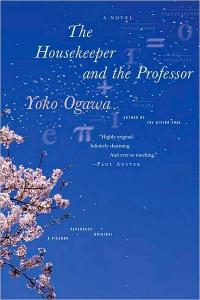

“‘It’s like copying truths from God’s notebook, though we aren’t always sure where to find this notebook or when it will be open.'” – The Housekeeper and the Professor, by Yoko Ogawa

As this novel opens, we learn that the Professor, a mathematician of some distinction, was seriously injured in a car crash some years ago. The accident severely impaired his memory; he needs constant reminders concerning day to day activities and has almost no ability to recall names and faces. Notes containing timely reminders are pinned to his clothing. He rarely leaves his house.

As this novel opens, we learn that the Professor, a mathematician of some distinction, was seriously injured in a car crash some years ago. The accident severely impaired his memory; he needs constant reminders concerning day to day activities and has almost no ability to recall names and faces. Notes containing timely reminders are pinned to his clothing. He rarely leaves his house.

His only near relation, a sister-in-law, lives nearby. She prefers to keep her interactions with the professor at a minimum. She hires a housekeeper to cook and clean for the professor. It is the housekeeper who tells us what happens next.

Not that much actually does happen: this is really the story of how three people come to know and care for one another. The third person is the housekeeper’s ten-year-old son. The Professor insists that the child come to his house after school, so that he will not be at home by himself while his mother is working. The little boy sports a buzz cut; as the Professor runs his hand over the top of the boy’s head, he is reminded of the sign for taking the square root of a number. Thereafter, the boy is called Root.

The author does not tell us the actual names of any of these characters; at times, I had the sense that I was reading a fable. The Professor’s little house contains these three people for most of the daylight hours, and their lives are progressively enriched by this close association. Ogawa’s writing, a model of grace and restraint, is the perfect vehicle through which to observe the process.

The discusions of mathematics were a revelation to me. Many of us recall struggling with math in school and being relieved to be released from its toilsome clutches. But even for the non-mathematically inclined like me, the conversations about numbers were a delight. Here, the housekeeper proudly shares a discovery that she has made on her own:

“‘The sum of the divisors of 28 is 28.’

‘Indeed…,[the Professor] said. And there, next to his outline of the Artin conjecture, he wrote: 28 = 1+2+4+7+14. ‘A perfect number.’

‘Perfect number?’ I murmured, savoring the sound of the words.

‘The smallest perfect number is 6: 6 = 1+2+3.’

‘Oh! Then they’re not so special after all.’

‘On the contrary, a number with this kind of perfection iss rare indeed. After 28, the next one is 496: 496 = 1+2+4+8+16+31+62+124+248. After that, you have 8,128; and the next one after that is 33,550,336. Then8,589,869,056. The farther you go, the more difficult they are to find’ – though he had easily followed the trail into the billions!

The Professor goes on to define ‘abundant numbers’ – those whose divisors add up to more tan the number itself – and ‘deficient numbers’ – those whose divisors add up to less than the number under consideration. An example of an abundant number is 18; its divisors – 1, 2, 3, 6, and 9 – when added up, equal 21. The number 14, on the other hand comes up short: its divisors – 1, 2, and 7 – only come to 10.

As she is taking all this in, the Housekeeper begins to play mind games of her own: “I tried picturing 18 and 14, but now that I’d heard the Professor’s explanation, they were no longer simply numbers. Eighteen secretly carried a heavy burden, while 14 fell mute in the face of its terrible lack.”

The lives of both the Housekeeper and Root are enriched by the Professor’s love of mathematics, and by his ability to communicate that love in a manner that is both lucid and joyous. For him, mathematical probing that fills his days is akin to peering into what he calls “God’s notebook.” Root and the Professor are also both great baseball fans. Almost inadvertently, the Professor’s love for that sport provides a key to a fuller understanding of his past.

Throughout this novel, the Housekeeper is self-effacing in the extreme. She portrays herself as merely the chronicler of these events, rather than as a participant of any particular importance. But it is her selflessness and generosity of spirit that make possible the string of little miracles that take place in the course of this narrative.

Ultimately, the Housekeeper characterizes the Professor thus:

“He treated Root exactly as he treated prime numbers. For him, primes were the base on which all other natural numbers relied; and children were the foundation of everything worthwhile in the adult world.

One of the great achievements of this slender volume consists in its simultaneous appeal to the intellect and to the emotions. The Housekeeper and the Professor, both original and profound, is a triumph of the novelist’s art.

Best books of 2009: my own favorites « Books to the Ceiling said,

December 20, 2009 at 2:50 am

[…] Hall by HilaryMantel Love and Summer by William Trevor To Heaven by Water by Justin Cartwright The Housekeeper and the Professor by Yoko Ogawa Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It by Maile Meloy In Other Rooms, Other Wonders by […]

Books to talk about – a personal view « Books to the Ceiling said,

March 8, 2010 at 1:22 pm

[…] Cleaver – Tim Parks Senator’s Wife – Sue Miller The Northern Clemency – Philip Hensher The Housekeeper and the Professor – Yoko Ogawa The Human Stain, Everyman – Philip Roth Hotel Du Lac – Anita […]